Note

Just a try, this is a good question by OP and I can't think of a direct clear cut answer to it.. but I'll try my best. Please comment if there are any logical mistakes in my answer.

The variables.

One thing I'd like to point your attention is that there are two variables here in the integration and differentiation. It is of $a$ and $x$. We integrate over $x$ and differentiate over $a$. It maybe noted that the final expression is entirely in $a$ because we 'integrate out' the variable of $x$. A quick example may help:

$$ \int_0^2 x dx = \frac{2^2}{2}$$

You may see that left side had expressions in $x$ and the right side is just a number

Feynman's trick (i.e: Leibniz rule under some simplifying assumptions)

Firstly, we are not exactly using the formula in the quoted text. We are using a simplified version of that. This version pop's out when you assume the bounds are constant:

$$ \frac{d}{dx} \int_a^b f(t,x) dt = \int_a^b \frac{\partial f(t,x)}{\partial x} dt$$

What we call Feynman's trick is usually the above result. Not the general quoted formula you have given. Due to this, we don't have to care for $\frac{db}{dx}$ or $ \frac{da}{dx}$.

You may be curious as to how to deal with the bounds varying, in that case understanding the total derivative will help you to understand that. Please see the answers to this question I have written.

If you are to insist on how to reduce Leibniz to this case, then..:

$$ \frac{d}{dx} \lim_{b \to \infty} \int_{0 }^{b(x)} f(x,t) dt= \lim_{ b \to \infty} \left[ f(x,b(x) ) \frac{db}{dx} + \int_{0}^{b} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dt \right]$$

Now, the problematic term is $\lim_{ b \to \infty}f (x,b(x) ) \frac{db}{dx}$, let's assume that both limits in product exist, this boils down the issue to:

$$ \lim_{ b \to \infty} \frac{db}{dx}$$

Question: Is $b$ parameterized by $x$ here? meaning, as you crank the $x$ variable, does $b$ change? answer:no. Hence we figure out that $b$ is a constant function of $x$:

$$ \frac{db}{dx} = \lim_{ h \to 0} \frac{b(x+h) - b(x)}{h} = \lim_{ h \to 0} \frac{b-b}{h} $$

Under application of l'hopital to the last equality., we find the derivative is zero at all points... and we recover Feynman's trick.

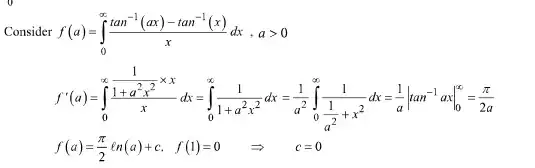

This is how this integral was evaluated .We differentiated this integral with respect to $a$ -

This is how this integral was evaluated .We differentiated this integral with respect to $a$ -