1) Matrix multiplication is the majority of deep learning and convolutional neural networks

In case you were under a rock, from 2012 on onwards deep learning algorithms have quickly become the best known algorithms for a variety of problems, including notably image classification, in which convolutional neural network (CNN) are used (deep learning with some convolution layers), and notably running on GPUs as opposed to CPUs.

And deep learning and convolutional neural networks are to a large extent (dense) matrix multiplication, both in the training and inference phases. This article explains it well: https://petewarden.com/2015/04/20/why-gemm-is-at-the-heart-of-deep-learning/ Basically two key stages can be reduced to matrix multiplications:

- fully connected layers

- convolution

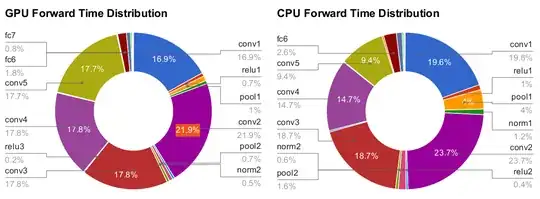

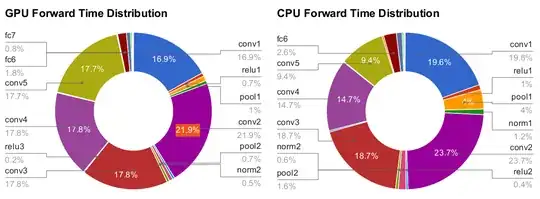

Benchmarks from this 2014 thesis by Yangqing Jia: https://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2014/EECS-2014-93.pdf showing that:

- convolution (

convX operations like conv1, conv2, etc.) make up basically the entire runtime of ImageNet's Krizhevsky et al. (AKA AlexNet)

fcX are fully connected layers. Here we see that they don't take up much time, possibly because the previous convolutional layers have already reduced the original image size by a lot

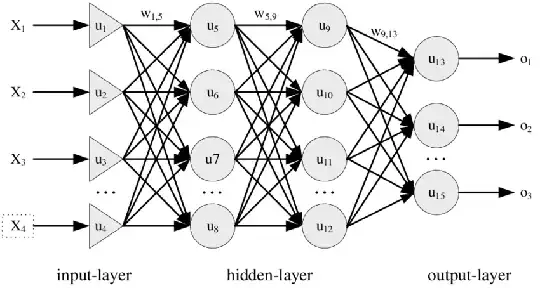

Fully connected layers

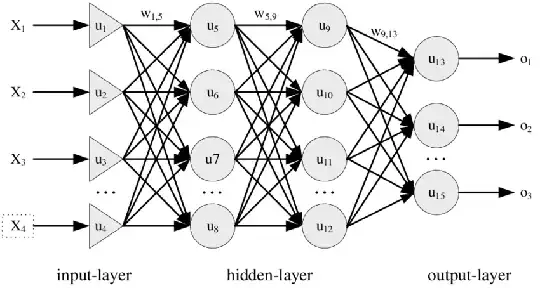

Fully connected layers look like this: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adhistya-Permanasari-2/publication/265784353/figure/fig1/AS:669201052209156@1536561372912/Architecture-of-Multi-Layer-Perceptron-MLP.png

Each arrow has a weight. The computation of the activation for layer is very directly a matrix-vector multiplication, where:

- inputs: vector with activation from previous layer

- matrix: contains the weights

- outputs: vector with activation for the next layer (to be followed by activation function)

We cannot further paralelize this as actual matrix-matrix multiplication however, it has to happen in sequence, because the value of one layer depends on the previous one being fully computed.

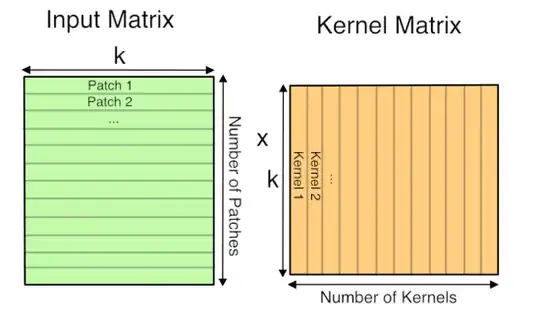

Convolution layers

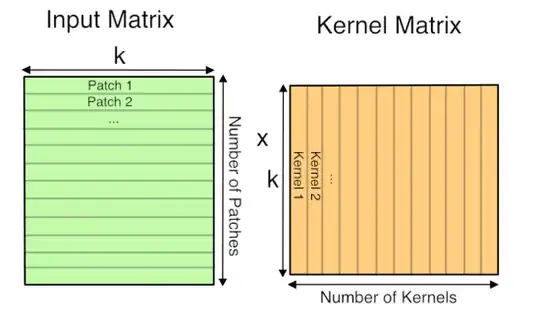

Convolution layers can actually be converted to matrix-matrix multipliation as shown at https://petewarden.com/2015/04/20/why-gemm-is-at-the-heart-of-deep-learning/ section "How GEMM works for Convolutions":

It may require some memory copying to put things in the right format however, which is a shame, but likely generally worth it, related: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/868568/what-do-the-terms-cpu-bound-and-i-o-bound-mean/33510470#33510470

Well explained at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aircAruvnKk But what is a neural network? | Chapter 1, Deep learning by 3Blue1Brown (2017)

2) 3D rendering applications

Some ideas at: https://computergraphics.stackexchange.com/questions/8704/why-does-opengl-use-4d-matrices-for-everything/13324#13324

3) Quantum computing

I guess this is directly linked to more general uses of matrix multiplication in quantum mechanics in general. But at least this use case is more specific and digestible for my brain.

In order to evaluate the output of a quantum circuit, we can first convert it to a matrix, which can be done deterministically.

Given an input, the probability of each output of a quantum circuit is found by doing matrix multiplication with that matrix.

Suppose we have a 3 qubit system. The inputs could be one of eight.

000

001

010

011

100

101

110

111

Given N qubits, the circuit matrix is $2^n \times 2^n$. For each input, we map it to a vector of size $2^N = 2^3 = 8$ as follows:

000 -> 1000 0000 == (1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

001 -> 0100 0000 == (0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

010 -> 0010 0000 == (0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

011 -> 0001 0000 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

100 -> 0000 1000 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

101 -> 0000 0100 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0)

110 -> 0000 0010 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0)

111 -> 0000 0001 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0)

The output of a 3 qubit circuit is necessarily 3 bits.

To obtain the probability of each output after an experiment, we simply multiply the 8-vectors by the 8x8 matrix.

Suppose that the result of this multiplication for the input 000 is:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\vec{q_{out}} &=

\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \\

0.0 \\

\frac{1}{2} \\

0.0 \\

0.0 \\

0.0 \\

0.0 \\

0.0

\end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}

$$

Then, the probability of each possible outcomes would be the length of each component squared:

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(000) &= \left|\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right|^2 &= \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}^2 &= \frac{3}{4} \\

P(001) &= \left|0\right|^2 &= 0^2 &= 0 \\

P(010) &= \left|\frac{\sqrt{1}}{2}\right|^2 &= \frac{\sqrt{1}}{2}^2 &= \frac{1}{4} \\

P(011) &= \left|0\right|^2 &= 0^2 &= 0 \\

P(100) &= \left|0\right|^2 &= 0^2 &= 0 \\

P(101) &= \left|0\right|^2 &= 0^2 &= 0 \\

P(110) &= \left|0\right|^2 &= 0^2 &= 0 \\

P(111) &= \left|0\right|^2 &= 0^2 &= 0 \\

\end{aligned}

$$

so in this case, 000 would be the most likely outcome, with 3/4 probability, followed by 010 with 1/4 probability, all other outputs being impossible.

Therefore, if 000 is the correct output for input 000, then we can reach arbitrary confidence that the result is correct by running the experiment over and over.