What is the volume of an n-dimension cube? Consider the length of each side to be $a$. How to solve this problem?

2 Answers

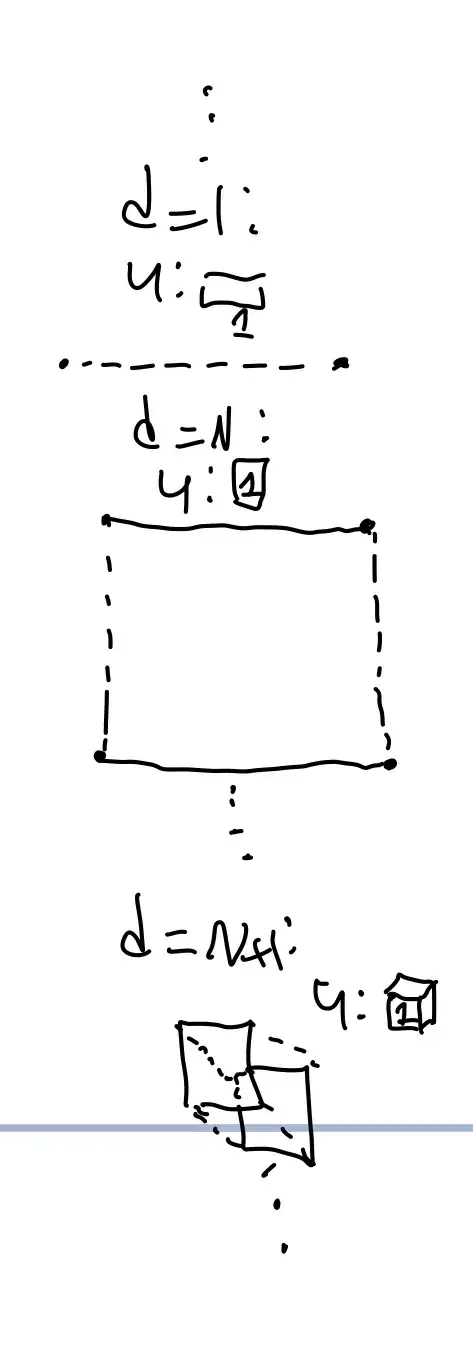

Perhaps it would be easier to imagine the volume of the cube to be the "n-dimensional area". Let's consider what happens in 1D, 2D and 3D first:

n=1:

In the first dimension, the volume would be just the side length or a=$a^1$.

For n=2:

This would be the square whose side length is a and the area is $a^2$

For n=3:

This would be the cube with volume of a^3.

For n>3:

I could do an induction proof on the conclusion, however a more intuitive pattern starts to emerge:

having the dimension be $0<n\in\Bbb Z$, would most certainly mean that Volume(n-dimensional cube with side length a)=V(a,n)=$a^n$. Keep in mind that the units would be $(units)^n$ for the n-dimensional area of an n-dimensional shape with the above restrictions, The dimension should a counting

The reason I said that an induction proof would not be as good is because I am not at the level of education to do this. I know how to do a very basic induction proof, but I am unconfident for this one. I guess it would go like this:

A line has n units which I will call u which are line segments so u+u+u+...+u=nu similarly, a square has square units, but also a certain amount of squares in one line segment like row so this would be nu+nu+...nu n times getting us $n^2$ u. We have this dimension being d=2 with n d=1 shapes “within” it. number, ie a positive integer excluding zero.

The reason I said that an induction proof would not be as good is because I am not at the level of education to do this. I know how to do a very basic induction proof, but I am unconfident for this one. I guess it would go like this: A line has n units which I will call u which are line segments so A=u+u+u+...+u=nu similarly, a square has square units, but also a certain amount of squares in one line segment like row so this would be A=nu+nu+...nu n times getting us $n^2$ u. We have this dimension being d=2 with n d=1 shapes “within” it. This means that our “hypothesis” is a d=N+1 cube has n of the d=N cubes “within” it using the same dimension units. The abbreviation u represents any general unit to the n-th power.

All in all, a d=N+1 cube can be drawn by connecting the corresponding vertices of a d=N cube assuming the connecting edge length is equal to the d=N cube edge length. This means that the hypothesis is “argued out” and so is informally correct with A=($n^{N}+...+n^{N})*u$ n times getting us A=n^{N+1}*units^{N+1}.

If a unit was instead defined by,say a n-tetrahedron, these formulas would not be correct for the space as it would likely be transformed.

I am not completely sure about the zeroth dimension nor fractal/fractional dimensions nor complex dimensions nor other types of dimensions here like negative dimensions.

Here are some links to these other dimensions:

Has the notion of having a complex amount of dimensions ever been described? And what about negative dimensionality?, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fractal_dimension, Imaginary and Complex Dimensions

Maybe there are other dimensions?

- 13,576

-

-

I wouldn't be human if I could resist mentioning this obvious oversight in your analysis. – user2661923 Apr 01 '21 at 16:12

-

I have attempted to prove this by induction, however I am struggling to conculde the proof. Would you be able to post the induction in an edit? – benmcgloin Apr 15 '21 at 14:43

-

@benmcgloin I tried doing an induction reasoning proof. I could not go into the units, but it is what I have. Correct me or give me feedback! – Тyma Gaidash Apr 15 '21 at 21:51

-

1$$V(B) =\prod_{i=1}^n (b_i -a_i)$$ This is the formula for the volume of a box in n dimensions. I centred it on the origin for simplicty. Given this we are left with:$$V(n)=\prod_{i=1}^n2x_i, n=2: V(2)=2^2x_1x_2$$ By observation we can see V(2) is true. Assuming the induction hypothesis that for an arbitrary k, the singular case n=k holds, meaning V(k) is true. $$V(k)=\prod_{i=1}^k2x_i=2^k(x_1x_2...x_k)$$ It follows that: $$V(k+1)=2^{k+1}(x_1x_2...x_kx_{k+1})=2^k(x_1x_2...x_k)2x_{k+1}$$ I am unsure of how to proceed here. I do not believe I can finish by saying $V(k+1)=2V(k)x_{k+1}$. – benmcgloin Apr 15 '21 at 22:01

-

@benmcgloin First of all, this can be simplified as here a cube is being talked about, but it is interesting to use a box in general. Maybe try doing $$K=i-1 ⇒i=1:K=0,i=k+1:K=k+1-1=k$$ getting us: $$V(K)=2^K(x_0x_1...x_{K-1}x_K)$$

As there are no other products we can put back in the original variable:$$V(k)=2^k(x_0x_1...x_{k-1}x_k)=\prod_{i=0}^k 2x_i$$ This looks like the original volume in the hypothesis formula but just with one extra term. I guess you add in that:

$$V(k+1)=x_0V(k)$$ meaning V(k+1 d-box)=V(k d-box) times the new side length from the new dimension. QED?

– Тyma Gaidash Apr 15 '21 at 23:06 -

Also, how do you know that the volume of a box is a “pure”product? Just saying “by observation”, even if I may have used this in my “proof” is not rigorous. How do you know the volume of a 2-d box is $$V(2)=4x_1x_2$$? Also we could simplify this by just doing $$2x_i=X_i$$ giving us $$V(k+1)=X_0\prod_1^k X_i = X_0V(k)=\prod_0^k X_i$$? – Тyma Gaidash Apr 15 '21 at 23:25

-

That seems like a viable conclusion, I suppose we could also validate $V(2)$ by using a double integral. $$\int_{0}^{2h} \int_{0}^{2l}dxdy=2^2hl=2^2x_1x_2$$ Unfortunately I do not have time to rigorously go through your comments tonight. I look forward to doing so tomorrow. – benmcgloin Apr 15 '21 at 23:59

-

1@benmcgloin It says to avoid discussions in comments.

You could also use the integral technique to prove the induction without induction. This can be done with the iterated integral formula being transformed into the product.

– Тyma Gaidash Apr 16 '21 at 00:59 -

Also, using the integral is like using a box to find the area of another box is circular reasoning because that is the definition of the integral to use rectangles. So, this would not work too well. We can instead use Simpson’s rule or the trapezoid rule if these are not circular reasoning. Correct me though. – Тyma Gaidash Apr 16 '21 at 11:56

The "area" of this shape can be thought of as multiplying each of the side lengths together for $n$ sides. So we could say that the area is $a^n$, where $n$ is the dimension of Euclidean space you're working in and $a$ is the side length of one of the sides of the hypercube ($n$-dimensional cube)

-

I agree and adding on, you can visualize the volume being as just a cube but with more dimensions giving the volume to be a to the power of n in abstract terms – I am a person Apr 01 '21 at 15:24