This is a realization I wish I had decades ago. I have learned multiple approaches to tensors and related topics. The one I have found most arcane and intractable is differential forms. I am still waiting to see the wisdom of $\partial_x=\mathbf{e}_x,$ and the banishment of the contravariant basis vector from polite conversation in favor of the hungry $dx$. But those are a different matter.

My question is: are the following statements correct?

Let $\mathcal{M}$ be an alternating $k$-linear function in $\mathbb{R}^{n}.$ To obtain its components we find its values on every combination of the $n$ standard basis vectors taken $k$ at a time. Since $\mathcal{M}$ evaluates to zero for any repeated basis vector, we need only consider unique sets, of which there are

$$ \begin{pmatrix}n\\ k \end{pmatrix}=\frac{n!}{k!\left(n-k\right)!}. $$ For each set of $k$ unique basis vectors, there are $k!$ permutations. Thus there is a total of

$$ k!\begin{pmatrix}n\\ k \end{pmatrix}=\frac{n!}{\left(n-k\right)!} $$

components $M_{i_{1}\dots i_{k}}$ which are not identically zero. But due to the skew-symmetry, there is only one component per unique set of $k$ index values. Permutation of any one of those unique sets merely toggles the algebraic sign of the component. Nonetheless, we need to use all of these components, because the contraction of this rank-$k$ covariant tensor with a set of $k$ contravariant vectors requires visiting all permutations of the index values.

Let there be $k$ vectors and their tensor product $$\begin{aligned} \mathfrak{v}_{j}&=\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{s}v_{j}^{s}\in\mathbb{R}^{n},\\ \mathfrak{V}&=\prod_{j=1}^{k}\mathfrak{v}_{j}=\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{i_{1}}\dots\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{i_{k}}V^{i_{1}\dots i_{k}}=\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{\mathfrak{i}}V^{\mathfrak{i}}, \end{aligned}$$ where $\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{i_{j}}$ are the standard (covariant) basis vectors of $\mathbb{R}^{n},$ and $\mathfrak{i}$ is a $k$-multi-index, as is $\mathfrak{j}$ following.

To find the value of $\mathcal{M}\left(\mathfrak{V}\right)$ we may contract in the standard way as for any tensors

$$ \mathcal{M}\left(\mathfrak{v}_{1},\dots,\mathfrak{v}_{k}\right)=M_{i_{1}\dots i_{k}}v_{1}^{i_{1}}\dots v_{k}^{i_{k}}=M_{\mathfrak{i}}V^{\mathfrak{i}}. $$

We could even write

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal{M}\left(\mathfrak{V}\right)&=\mathcal{M}\odot\mathfrak{V}=M_{\mathfrak{i}}\mathfrak{\hat{e}}^{\mathfrak{i}}\odot\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{\mathfrak{j}}V^{\mathfrak{j}}\\ &=M_{i_{1}\dots i_{k}}\mathfrak{\hat{e}}^{i_{1}}\cdot\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{j_{1}}\dots\mathfrak{\hat{e}}^{i_{1}}\cdot\hat{\mathfrak{e}}_{j_{k}}v_{1}^{j_{1}}\dots v_{k}^{j_{k}}\\ &=M_{i_{1}\dots i_{k}}v_{1}^{i_{1}}\dots v_{k}^{i_{k}}, \end{aligned}$$

using the vulgar profanity of contravariant basis vectors. And even worse, dotting them with covariant basis vectors!

This will give the same result as we get when $\mathcal{M}$ is expressed on a $k$-form basis of increasing $\mathfrak{i}$ $k$-tuples

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal{M}&=M_{\left\lfloor \mathfrak{i}\right\rfloor }d\tilde{x}^{\mathfrak{i}},\\ \mathcal{M}\left(\mathfrak{V}\right)&=M_{\left\lfloor \mathfrak{i}\right\rfloor }d\tilde{x}^{\mathfrak{i}}\left(\mathfrak{V}\right)=M_{\left\lfloor \mathfrak{i}\right\rfloor }\left|\mathfrak{V}^{\mathfrak{i}}\right|. \end{aligned}$$

That is to say $$ \mathcal{M}\left(\mathfrak{V}\right)=M_{\left\lfloor \mathfrak{i}\right\rfloor }d\tilde{x}^{\mathfrak{i}}\left(\mathfrak{v}_{1},\dots,\mathfrak{v}_{k}\right)=M_{i_{1}\dots i_{k}}v_{1}^{i_{1}}\dots v_{k}^{i_{k}}. $$ Where we used $$d\tilde{x}^{\mathfrak{i}}=dx^{i_{1}}\wedge\dots\wedge dx^{i_{k}}.$$

So this confirms that a $k$-form is the same thing as a completely antisymmetric rank-$k$ covariant tensor. One very good reason for using the wedge product basis is that it illuminates the nature of this kind of tensor evaluating as the sum of determinants.

The shocking truth

My current understanding is that $$\tilde{\alpha}=\mathit{a_{\left\lfloor \mathfrak{n}\right\rfloor }}d\tilde{x}^{\mathfrak{n}}= \mathit{a_{ i_1\dots i_k}}dx^{i_1}\dots dx^{i_k}.$$

Where $dx^{i_1}\dots dx^{i_k}$ are standard (symmetric) tensor products. That is, all of the alternating properties of the wedge product leading to determinants is contained in the algebraic signs of the "raw" tensor components.

(Good) Old-school versus differential forms

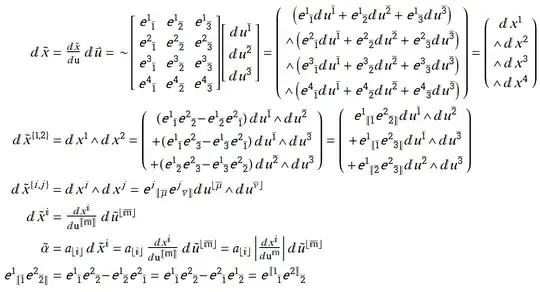

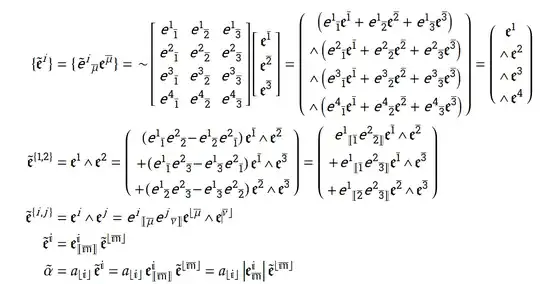

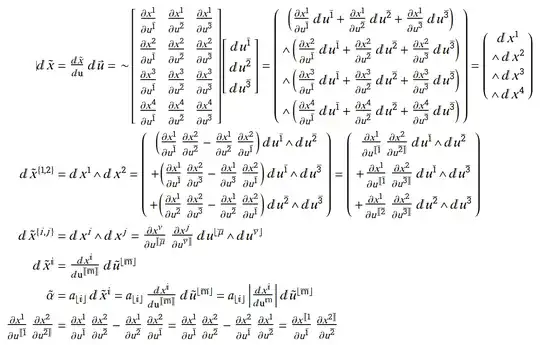

It's too difficult to hand-jam this stuff into mathjax, so I's screen-scraping. I use floor brackets $\left\lfloor \mathfrak{i}\right\rfloor $ to indicate increasing multi-indexing, where Edwards (but not Shifrin) uses $\left[\dots\right].$ My universal commutator, which I am calling the determinator in this context, is written $\left[\![\dots\right]\!].$ Its meaning should be evident from the context. $\mathbb{i}$ and $\bar{\mathbb{m}}$ are $k$-place multi-indices ranging over $n$ and $m$, respectively. Raised indices indicate contra-variant components. Lowered indices indicate covariant components.

The derivative matrix is written to emphasize that the rows are components of the contra-variant basis vectors $\mathfrak{e}^i$ of the ${\mathbb{R}^n}$-space expressed on the contra-variant basis $\mathfrak{e}^\bar{\mu}$ of the ${\mathbb{R}^m}$-space. The columns are the covariant basis vectors of ${\mathbb{R}^m}$-space, expressed on the covariant $\mathfrak{e}_\bar{\mu}$.

The $~$ indicates its subject is alternating (there's a wedge in it). I am hoping I've chased all of the twiddles to their logical end.

$\tilde\alpha$ is a $k$-form where the expression on $\mathbb{R}^n$-space is set equal to its pull-back to $\mathbb{R}^m$-space. Which is another thing I found confusing about pull-backs. They seemed like non-operations to me.

Notice the transitive nature of the determinator shown in the last line.

Mixed basis vector and differential notation

A $k$-form sans Cartan

I learned tensors from older books such as the horribly typo-ridden translation of Hermann Weyl's Raum-Zeit-Materie http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/43006 which speaks of covariant, contra-variant, invariant and contra-gredient properties.

The members of the cult of Cartan have typically insisted that those concepts are "old-school" and not particularly useful, or even wrong.

The French version

At the same time I was being told that everything I knew was useless or even wrong, I was trying hard to put the concepts of differential forms into the framework used by such people as Einstein to achieve their greatest accomplishments.

Not only is the "hungry operator" notation confusing, especially when trying to integrate it into established practices; but there is a widespread misunderstanding about what differential means to us unenlightened rubes who merely used them. More on that here: Differentials as "infinitesimals" versus as linear mappings or differential forms.

All of that said: There is an entirely different way of writing the same thing as the last version above, which is indisputably valuable.