In 'Introduction to graph theory' by Trudeau it is proved the theorem

Every graph has a genus

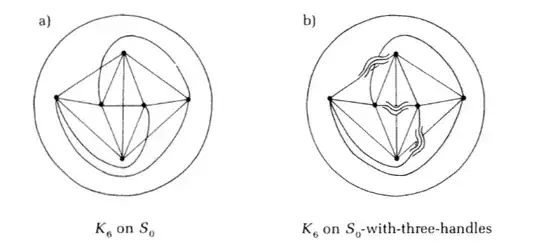

by first embedding the graph onto a sphere , and then adding handles, say we use $k$ of them, where the graph has edge-crossing , this is the example used :

Then, he writes that using a continuous deformation of the surface (stretching,shrinking or distorting the surface) it is possible to preserve planarity while deforming the $k$-handles sphere into a $k$-hole torus. So, the genus will be at most $k$.

I'm not able to visualize the bold part, how can I be sure that planarity will be preserved? Should it be obvious? Is there a simple explanation to understand clearly why this happens ? (I'm totally a beginner in algebraic topology, just visualization of trasformations are used in the book).

Another proof of a theorem stated earlier in the book : "every planar graph has genus $0$ (it can be embedded on a sphere)" was obscure to me but then searching online I found the explanation through the stereographic projection and all my doubts were gone , does something similar exist? Or even a good intuition is difficult to set up ?

EDIT :

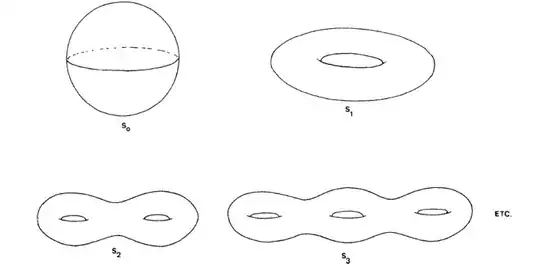

For clarity I add the definition of genus given in the book :

The genus of a graph, denoted $g$, is the subscript of the first surface among the family $S_0,S_1,S_2,\dots$ on which the graph can be drawn without edge crossing .

I also add the explanation of the author to pass from the $k$-handle sphere to the $k$-hole thorus :

Think of the surface consisting of $S_0$ with $k$ handles as made of extremely pliable rubber which we are free to stretch, shrink or otherwise distort as much as we want , provided that we don't tear it off of fold it back onto itself. With this understanding we see that the surface consisting of $S_0$ with $k$ handles can be 'continuously deformed' into $S_k$ and the vertices and edges of $G$ can be carried along with this continuos deformation. Thus $G$ can be drawn on $S_n$ without edge-crossings.

The bold part is obscure to me in the sense explained above.