There is indeed a physical meaning of trigonometric ratios for obtuse angles in the same way as for acute angles in a right triangle, which can be seen by analyzing the most basic and intuitive interpretation of trigonometric ratios for acute angles, namely ratios of sides in a right triangle w.r.t. the angle.

For some perspective, this is just like asking:

$1.$ If multiplication is repeated addition, what does multiplying by a negative number/fraction/irrational/imaginary number mean?

$2.$ If exponentiation is repeated multiplication, what does a negative integer/fractional/irrational/imaginary power mean?

The answers to these questions are that we are first taught that multiplication is repeated addition to understand it intuitively and then later extend it from the naturals all the way to complex numbers by using properties like $\frac{a}b=a÷b=a\times\frac1b$, the distributive property.

Similarly, after being taught that exponentiation is repeated multiplication, we extend it from natural numbers to complex numbers via laws of exponents like $a^{m-n}=\frac{a^m}{a^n}, (a^m)^n=a^{mn}, a^\frac1m=\sqrt[m]a$, Euler's formula $e^{ix}=\cos x+i\sin x$, etc. Sometimes, to make such extensions, we need to define certain things like what does it mean to multiply by a negative number, the derivative of $e^{ax}$ is $ae^{ax}$ always true even for complex $a$(for deriving Euler's formula). That is, we need to make some definitions/conventions so that we can extend these operations.

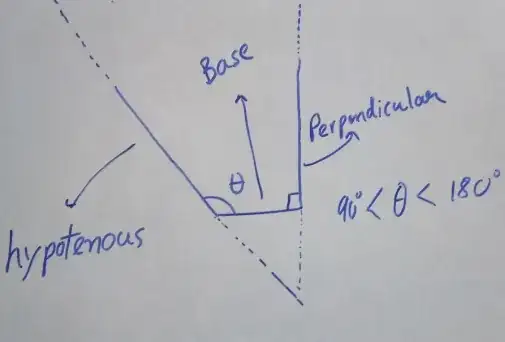

Similarly, to develop intuition regarding trigonometry, it is first taught that trigonometric ratios are ratios of sides within a right triangle with respect to an acute angle. This definition only works for acute angles. Then, after deriving properties like

$$\cos(x+y)=\cos x\cos y-\sin x\sin y$$

$$\sin(x+y)=\sin x\cos y+\cos x\sin y$$

$$\tan(x+y)=\frac{\tan x+\tan y}{1-\tan x\tan y}$$

We can now extend the domain of the arguments of trigonometric functions from $\left(0,\frac\pi2\right)$ to $(0,\pi)$. To extend till $\mathbb R$, we need a new, generalized definition for trig functions, namely relating them with the coordinates of a point on the unit circle on the basis of the angle subtended by the arc made by the point and $(1,0)$. This part has already been elaborated by @user2661923.

If we consider hyperbolic functions, then we can go further till $\mathbb C$ as well. See this Wikipedia page.

This way of extending intuitive definitions and adopting generalized definitions and conventions in pretty natural ways is indeed of great mathematical as well as physical significance as pointed out by @MarkBennet. For example:

$1.$ The dot product of $2$ vectors is dependent on the cosine of the angle between them. An application of this in Physics is work done by a constant force on an object, which is defined as $\displaystyle \int_{\text{path}}\vec{F}\cdot\vec{\mathrm dr}$. Intuitively, it may be thought of as the contribution provided by a force acting on a body in the direction of its velocity.

It can be proved and has been observed that the 'contribution' of a force acting in a direction perpendicular to the velocity of a moving body in the direction of its velocity is nothing, hence the work done by it is zero. This aligns with the statement $\cos\frac\pi2=0$.

If the force is directed opposite to its velocity, the force retards the body, viz., its 'contribution', hence work done is negative, which matches with the fact that the cosine of angles in the second Quadrant is negative.

$2.$ The magnitude of the cross product between $2$ vectors depends on the sine of the angle between them. An application of this in Physics is in defining torque, the rotational analogue of force $\vec\tau=\vec r\times\vec F$. Intuitively, it may be thought of as the rotational effect of a force.

Take the example of a hinged door and consider any point on the hinge from where we wish to write torque. If a force is applied on a point of the door in the direction of $\vec r$ of the point, the door doesn't rotate at all(compare this with $\sin0=0$). Then, as the angle between $\vec r$ and $\vec F$ increases, the rate of rotation produced increases till both vectors are at right angles, then decreases, which exactly matches with the behaviour of the sine function.

$3.$ Many trigonometric triangle identities, like area of a triangle $A=\frac12ab\sin\theta$ and the cosine rule beautifully hold food even for non-acute angles, although to prove them, we need to make $3$ cases: when the angle is acute, right and obtuse.