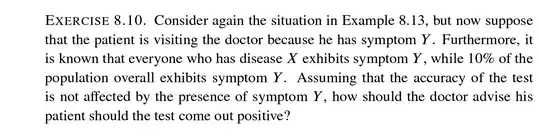

It means that $\mathsf P(A\mid B,C)=\mathsf P(A\mid B)$ and $\mathsf P(A\mid\overline B,C)=\mathsf P(A\mid\overline B)$; that is, that you can keep using the four numbers for the accuracy of the test in the first part and only have to adapt the $1\%$ rate of incidence (since the incidence among people with symptom $Y$ is higher).

This means that $A$ is conditionally independent of $C$ given $B$ or $\overline B$; that is, while $\mathsf P(A\mid C)\gt\mathsf P(A)$ (a person with symptom $Y$ is more likely than average to test positive for the disease), so that $A$ and $C$ are not independent, they become independent when you condition on $B$ or on $\overline B$. That is, the test accuracy only depends on the presence of the disease; it depends on the presence of the symptom only in that this makes it more likely that the disease is present, but given whether the disease is present, the symptom has no influence of its own on the test results. For more on conditional independence, you may want to take a look at Could someone explain conditional independence?.