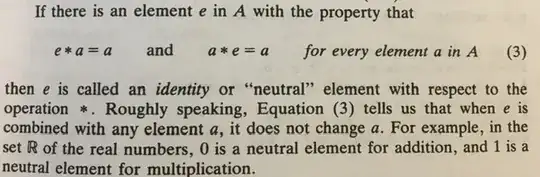

I'm working with the definition of an identity from Pinter's intro book on abstract algebra. He writes as follows:

I understand that if an operation has an identity it must be unique, which can be seen letting $e$ and $f$ be identities and noting that $e = e*f$ and $e*f=f$, so $e = f$. However — and I'm not sure how to word this — can there be specific non-identity elements on which another element has identity-like action?

Consider a later problem in Pinter's book where we identify that the operation

$$(a, b) * (c, d) = (ac, bc + d), \quad \text{on the set } \left(\mathbb{R}-\{0\}\right) \times \mathbb{R}$$

is a group with the identity element $e = (1, 0)$. But if we add the deleted zero back into the first coordinate's domain and do the same checks on that reformed $\mathbb{R}^2$ we run into the motivation for my question. I am not concerned with whether the operation still defines a group — it definitely does not since the inverse breaks — I am concerned with whether the identity still holds. It's still clear that $(1, 0)$ works for all elements in the new domain but it's not clear if it's acceptable that a specific element now has other identity-like relationships, like

$$(0, 0) * (x, 0) = (0, 0) = (x, 0) * (0, 0) \tag{$\star$}$$

Because there is still only one element as Pinter describes — one that works for every element in $\mathbb{R}^2$. My instinct is that the identity still holds, but I was reviewing an answer here: https://www.math.wisc.edu/~mstemper2/Math/Pinter/Chapter03B, problem 2 & 3, and the author states that $(\star)$ breaks uniqueness. So, to what part of the definition is uniqueness applied? It sounds like author of the linked answer has taken the converse as the definition.

Edit: Due to comments let me try to restate my problem more succinctly:

For a set and and a binary operation on that set, if there is/are some element(s) $a$ such that $xa=ax=x$ for many, possibly infinite choices of $x$, but only one element $e$ such $xe=ex=x$ for every $x$, is the property of the uniqueness of $e$ in the context of groups violated? What about for general sets with binary operations?

Edit2: I am utterly convinced that for a group

- There is only one identity element $e$

- There is no other element $e'$ in that group such that $xe'=e'x=x$

But I am not convinced that these statements are equivalent for operations on sets, only that they happen to coincide for a group. Based on Pinter's definition, I think that an identity for an operation on a set can be unique (statement 1), yet there may still be elements $e'$ in such that $xe'=e'x=x$ for some value of $x$ but not all. So in the linked answer when the author states

So this operation does not have a unique identity element.

I become confused because it isn't true. I don't see how it could ever be true. Of course this is probably just a quickly typed answer and the answerer meant to say group instead of operation, but the comments below are making me second guess this.