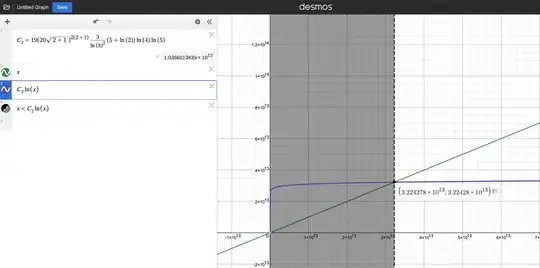

(Not a full proof yet) - If a counter-example exists, it must be $n\gt10^{10}$, so far.

Also, if $n_0$ is a counter-example, the next one is $\ge 3^{n_0-1}$, due to $\gamma_k$ sequence.

TL;DR I'll try to formalize my observation on your previous question and apply it here. But unlike your previous question, here we cannot factor the expression nicely. Consequently, instead of a direct closed form, we get a "nontrivial" set of recurrences $a_k,b_k,c_k$ that determine $v_3$.

To prove that no counter-examples exist, we must prove an upper bound on $a_k$ or $c_k$.

We inductively sieve $3$ congruence classes at every step $k$:

$$n\equiv n^{(k)}_1,n^{(k)}_2,n^{(k)}_3 \pmod{3^k}$$

We have $v_3(4^n+5)=k$ for $n\equiv n^{(k)}_1,n^{(k)}_{2}$ and $v_3(x_n)\gt k$ for $n\equiv n^{(k)}_3$.

Denote $a_k, b_k, c_k=n^{(k)}_1,n^{(k)}_2,n^{(k)}_3$ and notice that WLOG $a_k\lt b_k$.

This gives that $v_3(4^n+5)=k$ for the first time when $n= a_{k}$, giving:

$$

k\lt a_k \implies v_3(4^n+5)\lt k

$$

We have $k=n$, and hence need to show that $k\lt a_k$ for all $k\gt k_0=2$.

In other words, we have that $v_3(4^n+5)$ is given by:

$$v_3(4^n+5)=

\begin{cases}

1, & n\equiv 0,2 \pmod{3^1}\\

\dots\\

k, & n\equiv a_k,b_k \pmod{3^k}\\

\dots

\end{cases}$$

If we start to sieve the congruences, we obtain the congruence classes:

$$

\begin{array}{c|ccc|ccc|ccc}

k & &a_k& & &b_k& & &c_k& \\\hline

1 & 0 &=&0+0\cdot3^0 & 2 &=&0+2\cdot3^0 & 1 &=&0+1\cdot3^0 \\

2 & 1 &=&c_1+0\cdot3^1 & 4 &=&c_1+1\cdot3^1 & 7 &=&c_1+2\cdot3^1 \\

3 & 7 &=&c_2+0\cdot3^2 & 16 &=&c_2+1\cdot3^2 & 25 &=&c_2+2\cdot3^2 \\

4 & 25 &=&c_3+0\cdot3^3 & 79 &=&c_3+2\cdot3^3 & 52 &=&c_3+1\cdot3^3 \\

5 & 52 &=&c_4+0\cdot3^4 & 214 &=&c_4+2\cdot3^4 & 133 &=&c_4+1\cdot3^4 \\

6 & 376 &=&c_5+1\cdot3^5 & 619 &=&c_5+2\cdot3^5 & 133 &=&c_5+0\cdot3^5 \\

7 & 862 &=&c_6+1\cdot3^6 & 1591&=&c_6+2\cdot3^6 & 133 &=&c_6+0\cdot3^6 \\

8 & 133 &=&c_7+0\cdot3^7 & 2320&=&c_7+1\cdot3^7 & 4507&=&c_7+2\cdot3^7 \\

9 & 4507&=&c_8+0\cdot3^8 & 17629&=&c_8+2\cdot3^8 & 11068&=&c_8+1\cdot3^8 \\

10 & 30751&=&c_{9}+1\cdot3^{9} & 50434&=&c_{9}+2\cdot3^{9} & 11068&=&c_9+0\cdot3^{9} \\

11 & 70117&=&c_{10}+1\cdot3^{10} & 129166&=&c_{10}+2\cdot3^{10} & 11068&=&c_{10}+0\cdot3^{10} \\

12 & 188215&=&c_{11}+1\cdot3^{11} & 365362&=&c_{11}+2\cdot3^{11} & 11068&=&c_{11}+0\cdot3^{11} \\

13 & 11068&=&c_{12}+0\cdot3^{12} & 1073950&=&c_{12}+2\cdot3^{12} & 542509&=&c_{12}+1\cdot3^{12} \\

14 & 542509&=&c_{13}+0\cdot3^{13} & 3731155&=&c_{13}+2\cdot3^{13} & 2136832&=&c_{13}+1\cdot3^{13} \\

15 & 2136832&=&c_{14}+0\cdot3^{14} & 6919801&=&c_{14}+1\cdot3^{14} & 11702770&=&c_{14}+2\cdot3^{14} \\

16 & 26051677&=&c_{15}+1\cdot3^{15} & 40400584&=&c_{15}+2\cdot3^{15} & 11702770&=&c_{15}+0\cdot3^{15} \\

17 & 54749491&=&c_{16}+1\cdot3^{16} & 97796212&=&c_{16}+2\cdot3^{16} & 11702770&=&c_{16}+0\cdot3^{16} \\

18 & 11702770&=&c_{17}+0\cdot3^{17} & 269983096&=&c_{17}+2\cdot3^{17} & 140842933&=&c_{17}+1\cdot3^{17} \\

19 & 140842933&=&c_{18}+0\cdot3^{18} & 528263422&=&c_{18}+1\cdot3^{18} & 915683911&=&c_{18}+2\cdot3^{18} \\

20 & 915683911&=&c_{19}+0\cdot3^{19} & 2077945378&=&c_{19}+1\cdot3^{19} & 3240206845&=&c_{19}+2\cdot3^{19} \\

21 & 3240206845&=&c_{20}+0\cdot3^{20} & 10213775647&=&c_{20}+2\cdot3^{20} & 6726991246&=&c_{20}+1\cdot3^{20} \\

\dots &&\dots&& &\dots&& &\dots&

\end{array}$$

And so on...

$$

\begin{array}{c|c|c|c}

k &a_k=c_{k-1}+\alpha_k\cdot3^{k-1} & b_k=c_{k-1}+\beta_k\cdot3^{k-1} & c_k=c_{k-1}+\gamma_k\cdot3^{k-1} \\

\end{array}$$

Where we do see that $a_k,b_k,c_k$ grow much faster than $k$.

To prove this fact, we need to observe the $\gamma_k\in\{0,1,2\}$ multipliers in the $c_k$ column, because that column determines the record values.

It appears that the runs of consecutive zeroes $\gamma_k=0$ are extremely sparse (much shorter) compared to the growth of $3^k$, hence there should be no solutions other than $n=1$.

$$\gamma_k=1,2,2,1,1,0,0,2,1,0,0,0,1,1,2,0,0,1,2,2,1,\dots$$

But, at the moment, I'm not sure how to actually prove this observation for all $n$.

The first $21$ terms of $a_k,b_k,c_k$ in the table already give a large bound: If a counter-example exists, it must be at least $n\gt2\cdot 10^{10}$. (at least twice the size of the last $c_k$)