This answer assumes the following definitions

$$f_a(x)=\sum\limits_{n=1}^x a(n)\tag{1}$$

$$F_a(s)=s\int\limits_0^\infty f_a(x)\,x^{-s-1}\,dx=\underset{N\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^Na(n)\ n^{-s}\right),\quad\Re(s)\ge 2\tag{2}$$

where $f_a(x)$ and $F_a(s)$ are the summatory function and Dirichlet series associated with $a(n)$.

The analytic formulas for $a(n)$ in the PDF and question above are related to analytic formulas for

$$\tilde{f}_a(x)=\underset{\epsilon\to 0}{\text{lim}}\left(\frac{f_a(x-\epsilon)+f_a(x+\epsilon)}{2}\right)=\underset{N\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N a(n)\,\theta(x-n)\right)\tag{3}$$

and it's first-order derivative

$$\tilde{f}_a'(x)=\underset{N\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^N a(n)\,\delta(x-n)\right)\tag{4}$$

where $\theta(x)$ is the Heaviside step function and $\delta(x)$ is the Dirac delta function.

Consider the following analytic representations of $\tilde{f}_a(x)$ and it's first order derivative $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ where the evaluation frequency $f$ is assumed to be a positive integer. Formulas (5) and (6) below are based on this answer I posted to my own related question on MathOverflow.

$$\tilde{f}_a(x)=\underset{\substack{K,f\to\infty \\ K\gg f\,x}}{\text{lim}}\left(-4 f \sum\limits_{k=1}^K \frac{(-1)^k\ x^{2 k+1}}{2 k+1} \sum\limits_{j=1}^k \frac{(-1)^j\ (2 \pi f)^{2(k-j)}\ F_a(2 j)}{(2 k-2 j+1)!}\right)\tag{5}$$

$$\tilde{f}_a'(x)=\underset{\substack{K,f\to\infty \\ K\gg f\,x}}{\text{lim}}\left(-4 f\sum\limits_{k=1}^K (-1)^k\ x^{2 k}\sum\limits_{j=1}^k \frac{(-1)^j\ (2 \pi f)^{2(k-j)}\ F_a(2 j)}{(2 k-2 j+1)!}\right)\tag{6}$$

I believe formulas (5) and (6) above are exactly equivalent to

$$\tilde{f}_a(x)=\underset{K,f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^K b(n) \left(-\frac{\text{Si}(2 f \pi x)}{\pi}+\frac{x}{n} \sum\limits_{k=1}^{f\,n} \left(\text{sinc}\left(\frac{2 \pi (k-1) x}{n}\right)+\text{sinc}\left(\frac{2 \pi k x}{n}\right)\right)\right)\right)\tag{7}$$

$$\tilde{f}_a'(x)=\underset{K,f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^K b(n) \left(-2 f\,\text{sinc}(2 \pi f x)+\frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{k=1}^{f\,n} \left(\cos\left(\frac{2 \pi (k-1) x}{n}\right)+\cos\left(\frac{2 \pi k x}{n}\right)\right)\right)\right)=\underset{K,f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^K b(n) \left(-2 f\,\text{sinc}(2 \pi f x)+\frac{\sin(2 \pi f x) \cot\left(\frac{\pi x}{n}\right)}{n}\right)\right)\tag{8}$$

where the evaluation frequency $f$ is assumed to be a positive integer and

$$b(n)=\sum\limits_{d|n} a(d)\, \mu\left(\frac{n}{d}\right)\,.\tag{9}$$

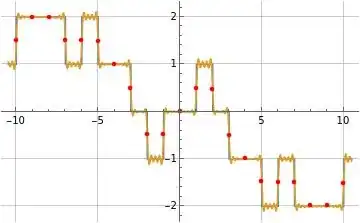

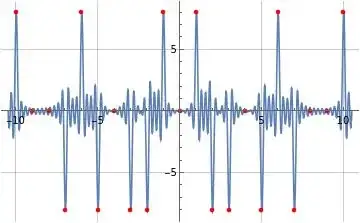

The following figure illustrates formula (7) for $\tilde{f}_a(x)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\mu(n)$ in orange overlaid on $\text{sgn}(x)\,M(|x|)$ in blue where $M(x)$ is the Mertens function and formula (7) is evaluated at $K=20$ and $f=4$. The red discrete portion of the plot represents the evaluation of formula (7) at integer values of $x$. Note formula (7) for $\tilde{f}_a(x)$ converges to $0$ at $x=0$ and is an odd function of $x$.

Figure (1): Illustration of formula (7) for $\tilde{f}_a(x)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\mu(n)$ (orange) overlaid on $\text{sgn}(x)\,M(|x|)$ (blue)

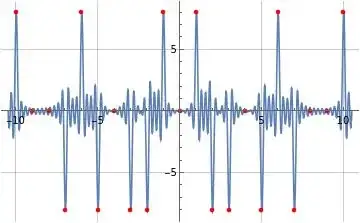

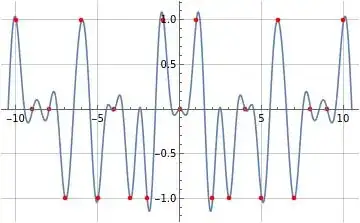

The following figure illustrates formula (8) for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\mu(n)$ where formula (8) is evaluated at $K=20$ and $f=4$. The red discrete portion of the plot represents the evaluation of formula (8) at integer values of $x$. Note formula (8) for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ converges to $0$ at $x=0$ and is an even function of $x$. Also note formula (8) converges to $2\,f\times a(|x|)$ at positive and negative integer values of $x$.

Figure (2): Illustration of formula (8) for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\mu(n)$

In the remainder of this answer $\tilde{a}(s)$ is used to refer to an analytic representation of the arithmetic function $a(n)$. The convergence of formula (8) for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ to $0$ at $x=0$ and to $2\,f\times a(|x|)$ at positive and negative integer values of $x$ leads to the following analytic representation which converges to $0$ at $s=0$ and to $a(|s|)$ at positive and negative integer values of $s$.

$$\tilde{a}(s)=\frac{1}{2\,f}\ \underset{K\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^K b(n) \left(-2 f\,\text{sinc}(2 \pi f s)+\frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{k=1}^{f\,n} \left(\cos\left(\frac{2 \pi (k-1) s}{n}\right)+\cos\left(\frac{2 \pi k s}{n}\right)\right)\right)\right)=\frac{1}{2\,f}\ \underset{K\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\sum\limits_{n=1}^K b(n) \left(-2 f \text{sinc}(2 \pi f s)+\frac{\sin(2 \pi f s) \cot\left(\frac{\pi s}{n}\right)}{n}\right)\right)\tag{10}$$

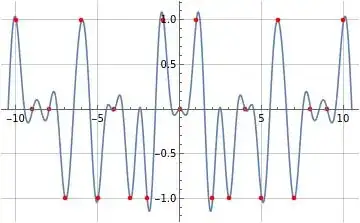

The following figure illustrates formula (10) for $\tilde{a}(s)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\mu(n)$ where formula (10) is evaluated at $K=20$ and $f=1$ (which is equivalent to the value used in the PDF and question above). The red discrete portion of the plot represents the evaluation of $\mu(|s|)$ at integer values of $s$. Note formula (10) for $\tilde{a}(s)$ converges to $0$ at $s=0$ and to $a(|s|)$ at positive and negative integer values of $s$.

Figure (3): Illustration of formula (10) for $\tilde{a}(s)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\mu(n)$

I illustrated formula (10) for $\tilde{a}(s)$ corresponding to $a(n)=\sigma _0(n)$ in this answer I posted to a related question on Math Overflow which also used the evaluation frequency $f=1$.

I've investigated the exact equivalence of formulas (5) and (6) above to formulas (7) and (8) above for cases such as the following where $\delta_n$ is the Kronecker delta function, $\sigma_0(n)$ is the divisor function, $\mu(n)$ is the Möbius function, $\Lambda(n)$ is the von Mangoldt function, $\zeta(s)$ is the Riemann zeta function, $\eta(s)$ is the Dirichlet eta function, $D(x)$ is the divisor summatory function, $M(x)$ is the Mertens function, and $\psi(x)$ is the second Chebyshev function.

Table (1): Example Cases

$$\left(

\begin{array}{ccccc}

a(n) & b(n)=\sum\limits_{d|n} a(d)\,\mu\left(\frac{n}{d}\right) & \text{Fa}(s)=\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{a(n)}{n^s} & \frac{\text{Fa}(s)}{\zeta(s)}=\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{b(n)}{n^s} & f(x)=\sum\limits_{n=1}^x a(n) \\

1 & \delta_{1-n} & \zeta(s) & 1 & \lfloor x\rfloor \\

(-1)^{n-1} & \delta_{1-n}-2\,\delta_{2-n} & \eta(s)=\left(1-2^{1-s}\right) \zeta(s) & 1-2^{1-s} & \lfloor x\rfloor -2 \left\lfloor\frac{x}{2}\right\rfloor \\

\delta_{1-n} & \mu(n) & 1 & \frac{1}{\zeta(s)} & 1_{x\ge 1}(x) \\

\sigma_0(n) & 1 & \zeta(s)^2 & \zeta(s) & D(x) \\

\mu(n) & \sum_{d|n} \mu(d)\,\mu\left(\frac{n}{d}\right) & \frac{1}{\zeta(s)} & \frac{1}{\zeta(s)^2} & M(x) \\

\Lambda(n) & -\log(n)\,\mu(n) & -\frac{\zeta'(s)}{\zeta(s)} & -\frac{\zeta'(s)}{\zeta(s)^2} & \psi(x) \\

\end{array}

\right)$$

Note in the first two rows in Table (1) above the upper evaluation limit can be terminated at $K=1$ and $K=2$ respectively since $b(n)=0$ for all larger values of $K$. Formulas (7) and (8) for the cases $a(n)=1$ and $a(n)=(-1)^{n-1}$ lead to the following formulas for the Riemann zeta function $\zeta(s)$ and Dirichlet eta function $\eta(s)$ which I believe converge for $\Re(s)<2$.

$$\zeta(s)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(2^s \pi^{s-1} \sin\left(\frac{\pi s}{2}\right) \Gamma(1-s) \left(-\frac{f^s}{s}+\frac{1}{2} \left(1+\sum\limits_{n=2}^f \left(n^{s-1}+(n-1)^{s-1}\right)\right)\right)\right),\ \Re(s)<2\tag{11}$$

$$\eta(s)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(2 \pi^{s-1} \sin\left(\frac{\pi s}{2}\right)\ \Gamma(1-s) \left(\frac{2^{s-1} f^s}{s}-\sum\limits_{n=1}^f (2 n-1)^{s-1}\right)\right),\ \Re(s)<2\tag{12}$$

Formulas (11) and (12) for $\zeta(s)$ and $\eta(s)$ above and the functional equations

$$\zeta (s)=2^s \pi^{s-1} \sin\left(\frac{\pi s}{2}\right) \Gamma(1-s) \zeta (1-s)\tag{13}$$

$$\eta (s)=2 \pi^{s-1} \sin \left(\frac{\pi s}{2}\right) \Gamma (1-s) \left(-\frac{1-2^{s-1}}{1-2^s} \eta (1-s)\right)\tag{14}$$

lead to the following formulas for $\zeta(s)$ and $\eta(s)$ which I believe converge for $\Re(s)>-1$.

$$\zeta(s)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\frac{f^{1-s}}{s-1}+\frac{1}{2} \left(1+\sum\limits_{n=2}^f \left(n^{-s}+(n-1)^{-s}\right)\right)\right),\ \Re(s)>-1\tag{15}$$

$$\eta(s)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\frac{1-2^{1-s}}{1-2^{-s}} \left(\frac{2^{-s} f^{1-s}}{s-1}+\sum\limits_{n=1}^f (2 n-1)^{-s}\right)\right),\ \Re(s)>-1\tag{16}$$

For the case $a(n)=\delta_{n-1}$ (Kronecker delta function) where $F_a(s)=1$, I believe formulas (7) and (8) above are exactly equivalent to

$$\tilde{f}_a(x)=-1+\theta(x+1)+\theta(x-1)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\frac{\text{Si}(2 f \pi (x+1))}{\pi }+\frac{\text{Si}(2 f \pi (x-1))}{\pi }\right)\tag{17}$$

$$\tilde{f}_a'(x)=\delta(x+1)+\delta(x-1)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(2 f\ \text{sinc}(2 \pi f (x+1))+2 f\ \text{sinc}(2 \pi f (x-1))\right)\tag{18}$$

in which case formula (8) above can be used to derive a series representation of $\delta(x)$ which I believe is exactly equivalent to the integral representation

$$\delta(x)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(\int\limits_{-f}^f e^{2 i \pi t x}\,dt\right)=\underset{f\to\infty}{\text{lim}}\left(2 f\ \text{sinc}(2 \pi f x)\tag{19}\right)$$

which I define in this answer I posted to one of my own questions on Math Overflow.

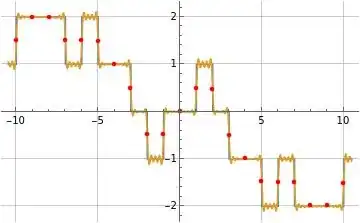

When I say formulas (5) and (6) above are exactly equivalent to formulas (7) and (8) above, I mean formulas (5) and (6) above are the Maclaurin series for the functions defined in formulas (7) and (8) above. Note the Maclaurin series for a function $g(x)$ is defined as $g(x)=\sum\limits_{m = 0}^\infty\frac{g^{(m)}(0)}{m!} x^m$. Since formula (7) for $\tilde{f}_a(x)$ is an odd function of $x$ (see Figure (1) above), all of the even coefficients in the related Maclaurin series defined in formula (5) above are zero. Since formula (8) for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ is an even function of $x$ (see Figure (2) above), all of the odd coefficients in the related Maclaurin series defined in formula (6) above are zero.

I've validated this equivalence using Mathematica for the first few values of $k$ in formulas (5) and (6) above for most of the cases defined in Table (1) above. This is easier to do when Mathematica understands the Dirichlet transform of $b(n)$ (i.e. the closed form representation of $\sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty b(n)\,n^{-s}$) which it does for the first four rows in Table (1) above but not for the last two rows. Evaluating this equivalence requires a little more work when Mathematica doesn't understand the Dirichlet transform of $b(n)$. For example, consider the following table for the first few Maclaurin series coefficients for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ for the case where $a(n)=\mu(n)$.

Table (2): Maclaurin Series Coefficients for $\tilde{f}_a'(x)$ for $a(n)=\mu(n)$

$$\begin{array}{cccc}

k & m=2 k & -4 f (-1)^k \sum\limits_{j=1}^k \frac{(-1)^j (2 \pi f)^{2 (k-j)}\frac{1}{\zeta (2 j)}}{(2 k-2 j+1)!} & \frac{1}{m!}\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} b(n) \underset{x\to 0}{\text{lim}}\left(\frac{\partial^m \left(-2 f\,\text{sinc}(2 f \pi x)+\frac{\cot \left(\frac{\pi x}{n}\right) \sin (2 f \pi x)}{n}\right)}{\partial x^m}\right) \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

1 & 2 & -\frac{24 f}{\pi ^2} & \frac{1}{2} \sum _{n=1}^{\infty } -\frac{4 \pi ^2 f b(n)}{3 n^2} \\

2 & 4 & 16 f^3-\frac{360 f}{\pi ^4} & \frac{1}{24} \sum _{n=1}^{\infty } \frac{16 \pi ^4 f b(n) \left(10 f^2 n^2-1\right)}{15 n^4} \\

3 & 6 & -\frac{4 f \left(4 \pi ^8 f^4-300 \pi ^4 f^2+4725\right)}{5 \pi ^6} & \frac{1}{720} \sum _{n=1}^{\infty } -\frac{64 \pi ^6 f b(n) \left(21 f^4 n^4-7 f^2 n^2+1\right)}{21 n^6} \\

\end{array}$$

The last two columns of Table (2) above can be validated as equivalent using the relationship $\sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty\frac{b(n)}{n^s}=\frac{1}{\zeta(s)^2}$ applicable to the case $a(n)=\mu(n)$. Take for example the second to last row in Table (2) above which can be verified as follows:

$$\frac{1}{24}\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{16 \pi ^4 f\,b(n) \left(10 f^2 n^2-1\right)}{15 n^4}=\frac{16 \pi ^4 f}{24\times 15} \left(10 f^2 \sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{b(n)}{n^2}-\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{b(n)}{n^4}\right)=\frac{16 \pi ^4 f}{24\times 15} \left(\frac{10 f^2}{\zeta (2)^2}-\frac{1}{\zeta (4)^2}\right)=16 f^3-\frac{360 f}{\pi ^4}\tag{20}$$