A polynomial in two variables, $t$ and $c$, is quintic in $t$ and quartic in $c$:

\begin{align} 16\,t^5 -8\,c (5\,c +2) t^4 +c^2 (25\,c^2+20\,c + 36) t^3& \\ -4\,c (11\,c^3+8\,c^2+5\,c+2) t^2& +8\,c^2 ( 3\,c^2+3\,c+2 ) t -4\,c^3 (c+2) \tag{1}\label{1} , \end{align}

\begin{align} (25 t^3-44 t^2+24 t-4)\,c^4 +(20 t^3-32 t^2+24 t-8)\,c^3 -4 t (10 t^3-9 t^2+5 t-4)\,c^2 -8 t^2 (2 t^2+1)\,c +16 t^5 \tag{2}\label{2} . \end{align}

It is related to An ancient Japanese geometry problem

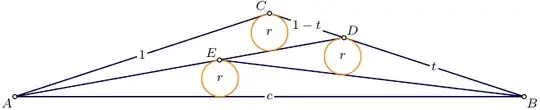

Given isosceles $\triangle ABC$ with legs $|AC|=|BC|=1$ and base $|AB|=c$, find $t=|BD|$ which provides the same radius for all three circles, inscribed in triangles $ADC$, $ABE$ and $BDE$.

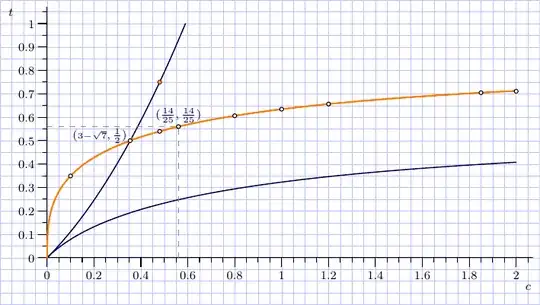

The roots of polynomial \eqref{1} provides the answer to this question, and for any valid value of $c\in(0,2)$ this quintic always has only three real roots.

This drawing demonstrates that zeros of \eqref{1} are presented by the three distinct branches.

Only one branch (the orange one) provides the pairs $(c,t)$ which correspond to correct geometric construction.

There are two "nice" points on that branch: one corresponds to the original sangaku, $t=c=0.56$, another one is located at the intersection of the two branches: $c=3-\sqrt7$, $t=0.5$.

Curiously, the valid range for $t$ is not $(0,1)$ as one might expect, so the quartic expression \eqref{2} may be misleading. For example, solving \eqref{2} for $t=\tfrac34=0.75$, we find $c=\frac{4\sqrt{61}-25}{13}\approx0.48$. However, since this $c\in(0,2)$, substituting this back into \eqref{2}, one gets the three real branches of the quintic as $t = 0.75, \, 0.5397, \,0.2284$ (approx) as can be seen in graph, with the correct solution being the middle one $t = 0.5397$ (approx).

So, the question is: is it possible to reduce the quintic \eqref{1} to a cubic?