Introduction

(This answer has been rewritten as a detour of Dirichlet convolution blog post by adamant)

Many sums of arithmetic functions like $\Phi(n) = \sum_{k\le n} \varphi(k)$ can be solved in sublinear time using the Dirichlet hyperbola method. Recall the Dirichlet convolution for arithmetic functions $f, g$:

$$(f * g)(n) = \sum_{d|n} f(d) g \left(\frac n d\right) = \sum_{ij = n} f(i) g(j) $$

$\newcommand{\floor}[1]{\left\lfloor #1 \right\rfloor}$

Let $F$ and $G$ be the summatory functions of $f$ and $g$, i.e. $F(x) = \sum_{i \le x} f(i)$ and $G(x) = \sum_{j \le x} g(j)$. These summatory functions have their domain extended to reals, as the indices are over positive integers $\le x$. Another way of putting it using only integer bounds is $F(x) := F(\floor{x})$. This will be useful for counting later.

We want to find the sum of the convolution, $\sum_{t \le n} (f * g)(t)$. Using the hyperbola method, we can compute this in terms of $f, g$ and their summation functions $F, G$.

From the first equation, the sum of the Dirichlet convolution is

$$

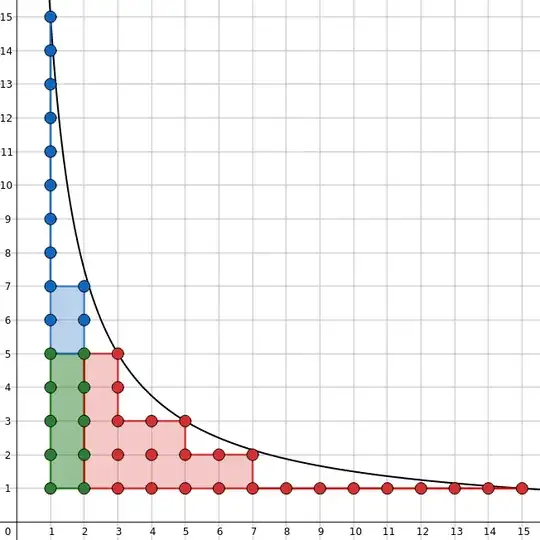

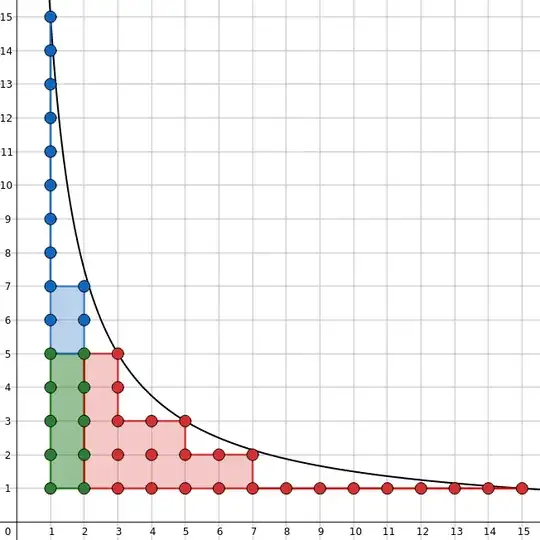

\sum_{t \le n} (f * g)(t) = \sum_{t \le n} \sum_{d | t} f(d) g \left( \frac t d \right) = \sum_{ij \le n} f(i) g(j)

$$

Lattice points under $ij = 15$. Credit: adamant.

Simplified hyperbola method

In our case, we start with the $\operatorname{Id} = \varphi * \mathbf 1$, another way of writing the identity

$$n = \sum_{d|n} \varphi(d) $$

We want to find $\Phi$, the sum of $\varphi$, and the sums of the others are easy: $\sum_{k\le n} \operatorname{Id}(k) = T(n)$, the triangular numbers, and $\sum_{k \le n} \mathbf 1 (k) = n = \operatorname{Id}(n)$. Thus in our case $f = \mathbf 1, F = \operatorname{Id}, g = \varphi, G = \Phi, f * g = \operatorname{Id}, \sum (f * g) = T$.

The key is that summation over $ij \le n$ is the hyperbola shape. The usual hyperbola method makes use of the fact that one of $i$ or $j$ is less than $\sqrt n$ (see below), but for this particular problem we can simplify the sum since $f$ is so simple.

Observe for each $i$, the values of $j$ under the hyperbola are from $1$ up to $n/i$. That is,

$$\sum_{ij \le n} f(i) g(j) = \sum_{i \le n} f(i) \sum_{j \le n/i} g(j)

= \sum_{i \le n} f(i) G \left( \frac n i \right)

$$

This identity is the starting point of the recursive algorithms:

$$

T(n) = \sum_{i=1}^n \Phi \left(\frac n i\right)

$$

By a generalization to the Möbius inversion formula,

$$\Phi(n) = \sum_{i=1}^n \mu(i) \ T \left( \frac n i \right)$$

Since $\mu(i)$ for range $[1,n]$ can be computed in linear time using a linear sieve, this gives a linear time and space algorithm. However, we can already use a small modification to the Sieve of Eratosthenes to compute $\varphi$ for the whole range in $O(n \log \log n)$ time, so we didn't make that much progress here.

Instead, the hyperbola shape suggests a sub-linear algorithm. Rearrange to solve for $\Phi(n)$:

$$\Phi(n) = T(n) - \sum_{i=2}^n \Phi \left(\frac n i \right)$$

The observation is that for large $i$ (consider $i \ge \sqrt n$), $\floor{n/i}$ is constant for many values. Let this cutoff point be $c = \floor{\sqrt n}$.

We can calculate precisely how many times each possible value occurs.

$$

\floor{\frac n i} =

\begin{cases}

1 & \text{if } n/2 < i \le n \\

2 & \text{if } n/3 < i \le n/2 \\

\vdots \\

c-1 & \text{if } n/c < i \le n/(c-1) \\

\end{cases}

$$

We can split the sum into two cases:

- Small $i$: $2 \le i \le n/c$

- Big $i$: $n/c < i \le n$, but we count by the distinct values of $j = \floor{n/i}$ instead

This gives us our final recursive formula:

$$\Phi(n) = T(n) - \sum_{2 \le i \le n/c} \Phi

\left(\frac n i \right)

- \sum_{j \le c-1}\left( \floor{\frac n j} - \floor{ \frac n {j+1} } \right) \Phi(j)

$$

What is the time complexity for the top level call $\Phi(N)$, assuming we memoize results? Since we chose $c \approx \sqrt N$, both summations each do about $\sqrt N$ recursive calls.

For $\Phi(N/i)$ term, all recursive calls use only values needed for the top-level $\Phi(N)$, as $\floor{\floor{N/i}/i'} = \floor{N/ii'}$. Assume for simplicity we can pre-compute all $\Phi(j)$ for $j \le \sqrt N$ in linear time, and retrieve values in $O(1)$. The total computation is bounded by something roughly like $\sum_{j=1}^{\sqrt N} O(1) + \sum_{i=2}^\sqrt N O(\sqrt{N/i}) = O(N^{3/4})$. See this answer by Erick Wong for more details.

The Codeforces post by adamant has a more detailed explanation and details on using pre-computed prefix sums for a better time complexity. The idea for this method is that you can compute $\Phi$ and prefix sums up to $c = n^{2/3}$ in linear time with a linear sieve, so $O(n^{2/3})$. Then we only need $\Phi(n/i)$ for $i$ up to $n/c = \sqrt[3]{n}$. The sum is computed in $\sum_{i=1}^{\sqrt[3]{n}} O(\sqrt{n/m}) = O(n^{2/3})$, which is balanced with the pre-computational cost. This is theoretically better than $O(n^{3/4})$, but at this point constant factors matter. In my experience, pre-computing up to $c = \sqrt n$ is the fastest.

Dirichlet hyperbola method

If we apply the simplified method to general functions $f, g$, for each $j$ there are $\sum_{n/(j+1) < i \le n/j} f(i)$ values, so the formula ends up as

$$

\sum_{i\le n} f(i) G \left(\frac n i \right)

= \sum_{i \le n/c} f(i) G \left( \frac n i \right)

+ \sum_{j\le c-1} \left( F \Bigl( \frac n j \Bigr)

- F \Bigl( \frac n {j+1} \Bigr) \right) G(j)

$$

The general Dirichlet hyperbola method considers for a cutoff point of $\sqrt n$ that at least one of $i$ or $j$ is $\le \sqrt n$. So we sum up points $i \le \sqrt n$ plus points $j \le \sqrt n$ minus overlap. This is essentially the same as the last formula, when we were more careful with counting to prevent overlap. This version highlights the symmetry much better.

$$

\sum_{ij \le n} f(i) g(j)

= \color{blue} {\sum_{i \le \sqrt n} f(i) G \Bigl( \frac n i \Bigr) }

+ \color{red}{ \sum_{j \le \sqrt n} g(j) F \Bigl( \frac n j \Bigr) }

- \color{green} { F(\sqrt n) G(\sqrt n) }

$$

Again we can choose a different cutoff covering all points using $i \le n/c$ and $j \le c$, if the computation times for $f, g, F, G$ are very different.

$$

\sum_{ij \le n} f(i) g(j)

= \color{blue} {\sum_{i \le n/c} f(i) G \Bigl( \frac n i \Bigr) }

+ \color{red}{ \sum_{j \le c} g(j) F \Bigl( \frac n j \Bigr) }

- \color{green} { F(n/c) G(c) }

$$