[I corrected the pictures and deleted one question due to user i707107's valuable hint concerning cycles.]

Visualizing the functions $\mu_{n\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}(k) = kn\ \ \mathsf{ mod }\ \ m$ as graphs reveals lots of facts of modular arithmetic, among others the fixed points of $\mu_{n\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}$ and the fact that $\mu_{n\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}$ acts as a permutation $\pi^n_m$ of $[m] = \{0,1,\dots,m-1\}$ iff $n$ and $m$ are coprime. Furthermore the cycle structure and spectrum of $\pi^n_m$ can be visualized and related to number theoretic facts about $n$ and $m$.

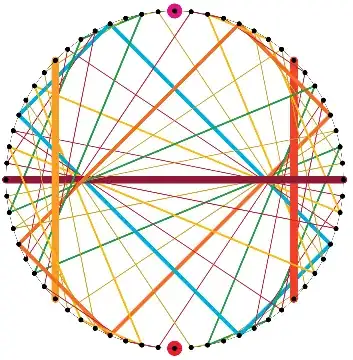

This is how the graph for $\mu_{3\ \mathsf{ mod }\ 64}(k) = 3k\ \ \mathsf{ mod }\ \ 64$ looks like when highlighting permutation cycles (the shorter the stronger):

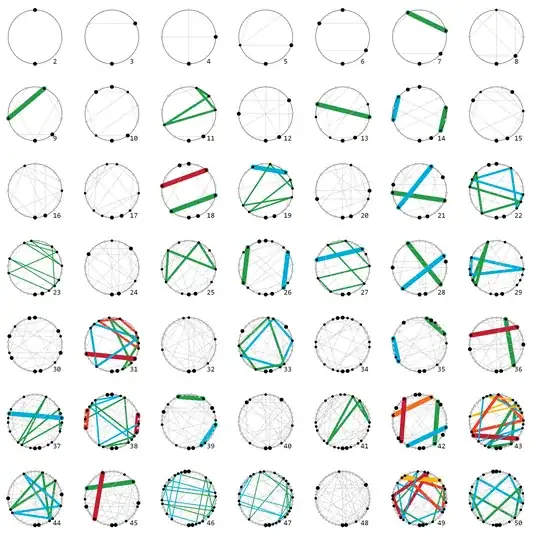

When visualizing the function $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}(k) = k^2\ \ \mathsf{ mod }\ \ m$ (which gives the quadratic residue of $k$ modulo $m$) in the same way as a graph, other observations can be made and tried to relate to facts of number theory, esp. modular arithmetic:

These graphs are not as symmetric and regular than the graphs for $\mu_{n\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}$ but observations can be made nevertheless:

the image of ${f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}}$, i.e. those $n$ with ${f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}}(k) = n$ for some $k < m$ (black dots)

number and distribution of fixed points with ${f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}}(k) = k$ (fat black dots)

cycles with ${f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}}^{(n)}(k) = k$ (colored lines)

parallel lines (not highlighted)

My questions are:

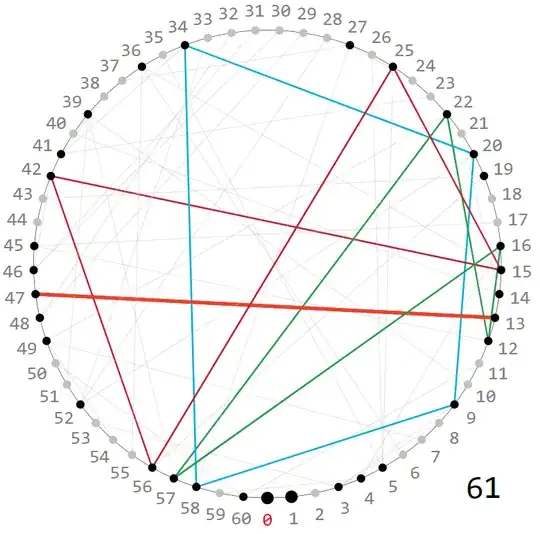

How can the symmetric distribution of image points $n$ (with $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ 61}(k)=n$ for some $k$, black dots in the picture below) be explained?

Can there be more than one cycle of length greater than 1 for $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ m}$?How does the length of the cycles depend on $m$?

How does the "parallel structure" depend on $m$?

With "parallel structure" I mean the number and size of groups of parallel lines. For example, $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ 8}$ has two groups of two parallel lines, $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ 12}$ has two groups of three parallel lines. $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ 9}$ has no parallel lines.

For $f^2_{\ \mathsf{ mod }\ 61}$ one finds at least four groups of at least two parallel lines:

For other prime numbers $m$ one finds no parallel lines at all, esp. for all primes $m\leq 11$ (for larger ones it is hard to tell).