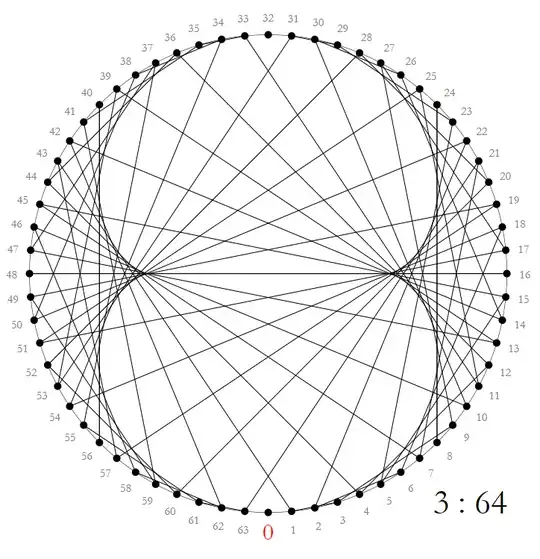

Let the multiplication graph $n:m$ be the graph with $m$ points equally distributed on a circle and a line between points $a$ and $b$ when $n\cdot a \equiv b\operatorname{mod} m$.

Looking at the multiplication graph $3:64$ with coprime $n, m$ reveals not so much at first sight – except of the ($n- 1$)-foil pattern that is to be expected for every "nominator" $n$:

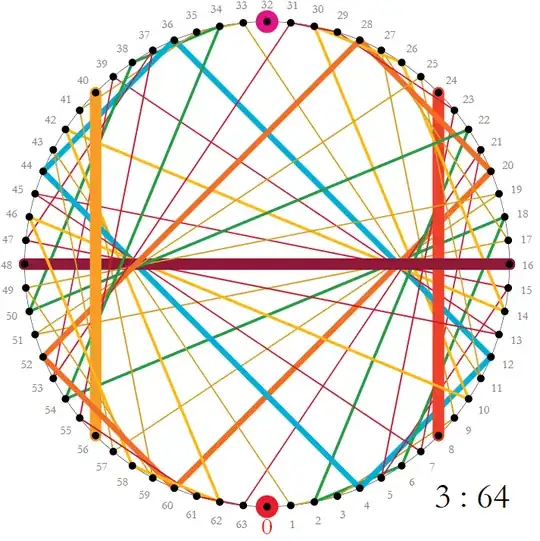

But when highlighting permutation cycles – the shorter the stronger – something interesting appears:

What one sees are two $4$-cycles $(4,12,36,44)$ and $(20,60,52,28)$ which describe two perfect rectangles with integral side lengths $8 : 24 = 1 : 3$

I wonder which properties of $n$ and $m$ are responsible for the appearance of two such rectangles and their corresponding side lengths? Is it by sheer coincidence that $8$ is the square root of $64$?