I am working on a problem on the infinite coin-tossing space and I'm having trouble making any meaningful progress.

Let $(\Omega, \mathcal F, P)$, where $\Omega=\{0,1\}^{\mathbb N}$, $F$ is the $\sigma$-field generated by the finite-dimensional sets, and $P$ is the coin(a fair coin) tossing probability. Finite dimensional sets are defined as sets $A=\{\omega\in\Omega\lvert(\omega_1,\omega_2,...,\omega_n)\in B\}$ for some $n\in\mathbb N$, $B\subset\{0,1\}^n$.

Define $X_n(\omega)=\omega_n \in\{0,1\}$ is the result of the nth toss and define $X(\omega)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} X_n(\omega)2^{-n}$.

- Show that the above series converges for every $\omega \in \Omega$ and defines a random variable taking values in $[0,1]$.

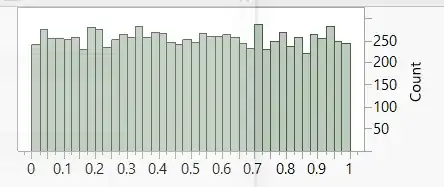

- Show that $X$ has uniform distribution on $[0,1]$.

My attempt:

I believe the series converges (absolutely) by using the comparison test with $\sum_{i=1}^\infty 2^{-n}$, as $X_n\leq 1$, and $\lvert X_n2^{-n} \rvert\leq\lvert2^{-n}\rvert$. Now I'm hoping to show that $$E=\{\omega :X(\omega)\in (a,b)\}\in\sigma(F)$$ as if that holds, I can conclude that any Borel set will be in $\sigma(F)$ as well, since $\{(a,b):a,b\in[0,1]\}$ generates all the Borel sets in $[0,1]$. Now I can certainly find $\omega$'s that will be in $E$, since $X$ is a binary expansion of some real number in $[0,1]$, but I'm a bit stuck at this point.

I was given a hint to find $P(X\in[i2^{-m},(i+1)2^{-m}])$ for $i=0,...,2^{m}-1$. I'm not sure how to find the probabilities, and how it can help to show that $X$ has a uniform distribution.

Any help on both questions would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.