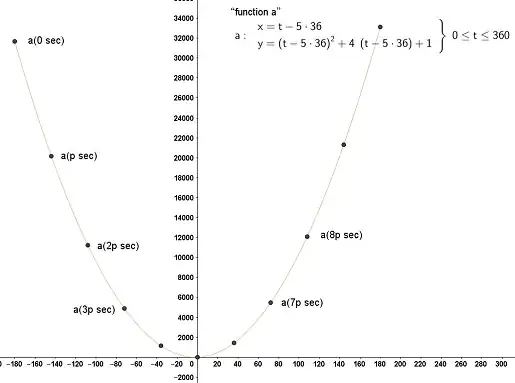

The laser beam is effectively a family of rays parameterized by time, which can be represented by the rotating unit vector $$\mathbf L(t) = (\cos\omega t, \sin\omega t),$$ where $\omega$ is the angular velocity of the ray. For simplicity, I’m assuming that the laser starts off pointing in the positive $x$-direction at $t=0$. You can always add a constant phase shift $\delta$ or offset the time if this is not the case. If you can come up with a time parameterization $\mathbf\gamma(t)$ of the object path, then the problem becomes one of finding the solutions to $\mathbf\gamma(t)=c\mathbf L(t)$, $c\ge0$.

In theory, finding this time parameterization is straightforward. Every regular parameterized curve can be reparameterized by arc length: if $\mathbf\gamma$ is regular, then the arc length function $$s(\lambda) = \int_a^\lambda \|\mathbf\gamma'(u)\|\,du$$ is an increasing differentiable function, so has a differentiable inverse $\lambda = \lambda(s)$. Setting $s=vt$ in this arc length parameterization of the curve then has the property that the object moves with constant speed $v$, as required. (You can verify this by an application of the chain rule.)

In practice, however, the arc length function for most curves doesn’t have a nice inverse, and in fact the arc length itself might not be expressible in terms of elementary functions. For instance, for your parabola, the arc length function derived in the answers to this question doesn’t have a closed-form inverse. Indeed, as Will Jagy notes in a comment to that question, a parabola is one of the few curves for which the arc length integral has a closed form, however ugly. Since we have $s=vt$, you could try solving $$c\left(\cos\left(\frac\omega vs(\lambda)\right),\sin\left(\frac\omega vs(\lambda)\right)\right) = \mathbf\gamma(\lambda)$$ for some convenient parameterization of the parabola, but that doesn’t look very promising, either. In general, you’re going to have to resort to numeric methods to solve this problem.