I am reading this paper (A Geometric Proof of the Perron-Frobenius Theorem, A. Borobia, U. R. Trias, Revista Mathematica de la Universidad Conplutense de Madrid, Vol. 5, 1992) where a short geometric proof of the Perron-Frobenius theorem is given. I am having trouble at one place, which I articulate below. I sacrifice some generality in service of simplicity.

Let $A$ be an $n\times n$ matrix with positive real entries and $T:\mathbf R^n\to \mathbf R^n$ be the linear map whose matrix representation with respect to the standard basis is same as $A$. Define $$C=\{(x_1, \ldots, x_n)\in \mathbf R^n:\ x_i>0\}, \quad \bar C=\{(x_1, \ldots, x_n)\in \mathbf R^n:\ x_i\geq 0\}$$

The following are true:

Theorem 1. There is a positive eigenvalue of $T$ with corresponding eigenvector in $C$.

Theorem 2. If $\lambda$ is an eigenvalue as in Theorem 1, then the geometric multiplicity of $\lambda$ is $1$.

Theorem 3. If $\lambda$ is an eigenvalue as in Theorem 1, then the algebraic multiplicity of $\lambda$ is $1$.

(Clearly, Theorem $3$ subsumes Theorem 2.)

Theorem 1 can be proved using Brouwer's fixed point theorem (BFPT). We notice that if $R$ is the collection of all rays in $\mathbf R^n$ of the form $\{av:\ a\geq 0\}$ for some $v\in \mathbf R^n$ having all entries non-negative, then $R$ is fixed, as a set, by $T$. But $R$ is homeomorphic to the $n-1$ disc, and thus by BFPT we see that there is some ray in $R$ that is fixed by $T$. This immediately gives $1$. (The fixed ray cannot lie in $\partial C$ because all entries of $A$ are positive.)

For Theorem 2 we argue as follows. Let $\lambda$ be a positive eigenvalue of $T$ with $v$ as a corresponding eigenvector, all of whose entries are positive. If the geometric multiplicity of $\lambda$ is not $1$, then there is a vector $u\notin \text{span}(v)$ with $Tu=\lambda u$. Let $V$ be the plane spanned by $u$ and $v$. Each ray in $V$ is fixed by $T$. But there is a ray in $V$ spanned by a vector in $\partial C$, which cannot remain fixed under $T$, giving a contradiction.

I am stuck with the proof of Theorem 3. The proof in the above-cited paper proceeds as follows. Let $\lambda$ be a positive eigenvalue with the corresponding eigenvector $v$ having all entries positive. Assume that the algebraic multiplicity of $\lambda$ is more than $1$. Then we can find a $T$-invariant plane $U$ containing $\text{span}(v)$. Let $S^1$ be identified with the set of rays in $U$. Let $r$ and $-r$ denote the rays spanned by $v$ and $-v$ respectively. By Theorme 2, $S^1$ is not point-wise fixed under the action of $T$.

And here is what I don't follow:

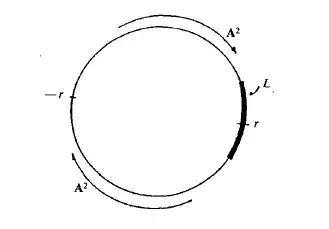

The set of points in $S^1$ which are fixed by the action of $T^2$ does not consist only of $r$ and $-r$. Other wise the dynamics of the action of $T^2$ over $S^1$ looks like this

Here $L$ is the arc of $S^1$ formed by the intersection of $S^1$ with the set of rays in $\bar C$.

EDIT: Why $T^2$ needs to have a fixed point apart from $r$ and $-r$ can be argued as follows: Assume on the contrary. Note that $T^2$ is orientation preserving. So the arc "above" the points $-r$ and $r$ (including $-r$ and $r$) is mapped to itself under $T^2$. Since this is homeomorphic to the closed interval, either all points in the open arc converge to $r$ under iterates of $T^2$, or all points of the open arc converge to $-r$ under iterates of $T^2$. But the sets $C$ and $-C:=\{-x:\ x\in C\}$ are invariant under $T^2$ so we get a contradiction.

Can somebody explain this last piece of reasoning. And how is it helping us deduce that the algebraic multiplicity of $\lambda$ is $1$. This argument is at the bottom of the second page of the paper I mentioned.