$\newcommand{\Map}{\textrm{Map}}\newcommand{\Sym}{\textrm{Sym}}$Unfortunately, you are interpreting something wrong… Let's try to make more sense out of it.

What that says to me is it is a homomorphism (function) $f\colon X\to S$ where $S$ is a set of bijective functions on $X$.

No, it doesn't say that. There are three different objects here, but you keep confusing them with other (in different ways throughout your post). Those three objects are:

- a group $G$,

- a set $X$,

- and the symmetric group of all bijective functions on $X$, which we may denote $S=\Sym(X)$.

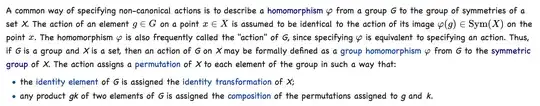

Now, the definition of a group action (of a group $G$ on a set $X$) says that is it a group homomorphism $f\colon G\to S$, i.e. $f\colon G\to\Sym(X)$. Note that the domain of the group action $f$ is $G$, not $X$ as you said.

… if we have … a group $(∗,\{4,5,6\})$ …

This is a bit hard to understand. I guess you're saying that we have a group $G=(∗,\{4,5,6\})$. Okay, so $\{4,5,6\}$ is the underlying set of this group, but it's not quite clear how the operation $*$ works. Since this is not one of the common standard notations for a concrete group (like $\mathbb{Z}$ or $V_4$), you should define it. Of course, since you're having a general discussion here and don't use this operation explicitly, I can't say that there's anything wrong with it per se. It is possible to define a group operation $*$ on the set $\{4,5,6\}$. But it would be a bit unusual considering the choice of the symbols for the elements of the group (for example, one of them — either $4$ or $5$ or $6$ — will have to be the identity element). So the only reason I am pointing this out is because I suspect it is also a sign of one of your confusions.

… the symmetric group of $X$ would be something like $S=\{1\to2,2\to3,\ldots\}$ …

Sorry, but this doesn't make much sense. We can say that an individual element of the symmetric group looks more or less like that. For example, if $X=\{1,2,3\}$, then one of the elements of $S=\Sym(X)$ is the bijective mapping $\sigma_1=\{1\mapsto2,2\mapsto3,3\mapsto1\}$, or rather $\sigma_1=\{(1,2),(2,3),(3,1)\}$ in ordered pairs notation. Another examples of an elements of $S=\Sym(X)$ is the bijective mapping $\sigma_2=\{1\mapsto2,2\mapsto1,3\mapsto3\}=\{(1,2),(2,1),(3,3)\}$. But then $S=\Sym(X)$ is the set of all such bijective mappings. In this example (hold your breath):

$$\begin{align}

S&=\{\sigma_1,\sigma_2,\sigma_3,\sigma_4,\sigma_5,\sigma_6\}, \quad \text{where}\\

\sigma_1&=\{1\mapsto2,2\mapsto3,3\mapsto1\}=\{(1,2),(2,3),(3,1)\},\\

\sigma_2&=\{1\mapsto2,2\mapsto1,3\mapsto3\}=\{(1,2),(2,1),(3,3)\},\\

\sigma_3&=\{1\mapsto3,2\mapsto2,3\mapsto1\}=\{(1,3),(2,2),(3,1)\},\\

\sigma_4&=\{1\mapsto1,2\mapsto3,3\mapsto2\}=\{(1,1),(2,3),(3,2)\},\\

\sigma_5&=\{1\mapsto3,2\mapsto1,3\mapsto2\}=\{(1,3),(2,1),(3,2)\},\\

\sigma_6&=\{1\mapsto1,2\mapsto2,3\mapsto3\}=\{(1,1),(2,2),(3,3)\},

\end{align}$$

listed in no particular order.

… and $\varphi$ would be something like $f\colon\{4,5,6\}\to S$.

Yes, under three conditions:

- you understand correctly what $S$ is;

- you clearly define a group structure, i.e. the multiplication operation $*$ on the group $G=\{4,5,6\}$;

- and you make sure that $f\colon G\to S$ is group homomorphism between the group $G=\{4,5,6\}$ with the operation $*$ and the group $S=\Sym(X)$ with composition as the group operation.