Originally this proof was part of the question statement.

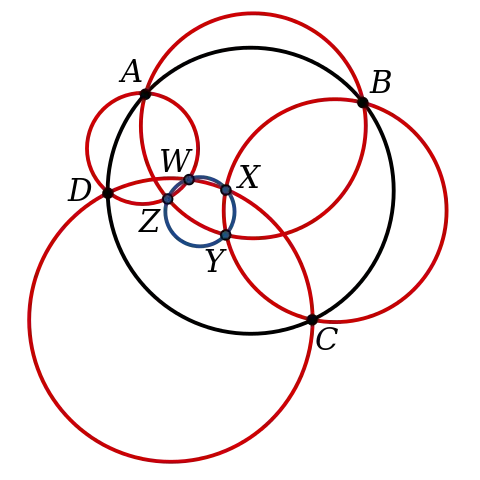

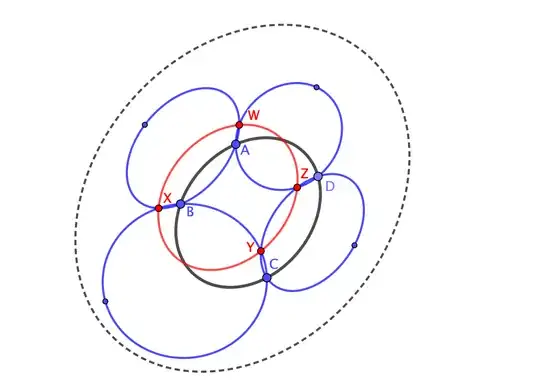

The proof I know uses the cross ratio in the complex plane. Consider your points as complex numbers. Then four points are cocircular (or collinear) if their cross ratio is real (as I will discuss in more detail below). So the circle $\bigcirc ABCD$ leads to the equation

$$(A,B;C,D)=\frac{(A-C)(B-D)}{(A-D)(B-C)}\in\mathbb R$$

and the other circles lead to similar equations. Furthermore, a different order of points on a circle leads to a different equation, too. Choosing the orders of points appropriately you can multiply all the cross ratios to obtain

$$

(A,C;B,D)\cdot(A,Y;Z,B)\cdot(C,Y;B,X)\cdot(C,W;X,D)\cdot(A,W;D,Z)=\\

\frac{\color{#00f}{(A-B)}\color{#090}{(C-D)}}{\color{#c00}{(A-D)}\color{#0cc}{(B-C)}}\cdot

\frac{\color{#c0c}{(A-Z)}\color{#660}{(Y-B)}}{\color{#00f}{(A-B)}(Y-Z)}\cdot

\frac{\color{#0cc}{(C-B)}(Y-X)}{\color{#09c}{(C-X)}\color{#660}{(Y-B)}}\cdot\\

\frac{\color{#09c}{(C-X)}\color{#900}{(W-D)}}{\color{#090}{(C-D)}(W-X)}\cdot

\frac{\color{#c00}{(A-D)}(W-Z)}{\color{#c0c}{(A-Z)}\color{#900}{(W-D)}}=\\

-\frac{(Y-X)(W-Z)}{(Y-Z)(W-X)}=-(Y,W;X,Z)

$$

so if all the original cross ratios were real, then so is the final one. Usually I'd formulate this in terms of homogeneous coordinates, writing $2\times2$ determinants instread of the differences, and taking the point at infinity from $\mathbb{CP}^1$ into account, but that's not all that relevant to this question here.

I learned this proof from Prof. Richter-Gebert at university, and his book Perspectives on Projective Geometry has a variation of this in section 18.5. There he describes a circle as a conic through the ideal circle points $[1:\pm i:0]$ but otherwise the approach is essentially the same: multiply all inputs and cancel terms.

Cross ratios and cocircularity

The underlying relationship between real cross ratio and cocircularity can be explained like this: Consider $(A-C)$ as the vector pointing from $C$ to $A$. Use

$$(A-C)=r_{CA}\exp\left(i\varphi_{CA}\right)$$

to express this vector in polar coordinates. Now

$$\frac{A-C}{B-C}=\frac{r_{CA}}{r_{CB}}

\exp\left(i\left(\varphi_{CA}-\varphi_{CB}\right)\right)$$

has an argument (angle) which depends on the difference of the angles of the individual vectors. And for the whole cross ratio you get

$$\frac{(A-C)(B-D)}{(A-D)(B-C)}=\frac{r_{CA}r_{DB}}{r_{DA}r_{CB}}

\exp\left(i\left(\varphi_{CA}+\varphi_{DB}-\varphi_{DA}-\varphi_{CB}\right)\right)$$

which is real iff

$$\varphi_{CA}+\varphi_{DB}-\varphi_{DA}-\varphi_{CB}\equiv0\pmod\pi\\

\varphi_{CA}-\varphi_{CB}\equiv \varphi_{DA}-\varphi_{DB}\pmod\pi$$

which translates to $\angle ACB\equiv\angle ADB$: two points $C$ and $D$ form the same (oriented) angle with the line segment $AB$. So this is essentially just a form of the inscribed angle theorem. As a special case, if the differences on both sides of the equation are zero, the four lines are collinear.