Question: Find the probability that a random pair of lattice points are opposite corners of a square in an $n\times n$ integer lattice.

Note: By a square in a lattice, I mean a square whose vertices are all lattice points.

Motivation: I have a messy proof that the solution is $\frac13$. The proof relies on calculating the total number of squares in each $n\times n$ lattice, but I want to know if there is some neat argument which avoids that method. There's reason to think there might be since the result is independent of $n$.

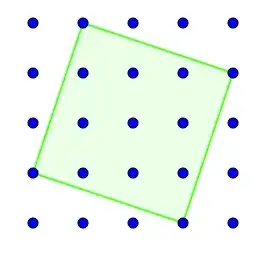

Background: First notice that in an $n\times n$ integer lattice, there are more squares than the obvious axis-aligned squares, for example the following:

With some calculation, one can find that the total number of squares in this grid is $$\sum\limits_{k=1}^nk^2(n-k)=\frac{(n-1)n^2(n+1)}{12}$$ I noticed that this can also be written as $\dfrac{n^2 \choose 2}{6}$, which led me to the combinatorial interpretation of picking corners of a square. Once we know that the number of squares is $\frac{1}{6}$-th of the number of pairs of points, the claimed solution of $\frac13$ is an immediate consequence (as each square has two pairs of opposite corners). However, I've searched for the past week and failed to discover a proof without relying on counting all the squares.

Source: I thought of this question while trying to write problems for a math competition.