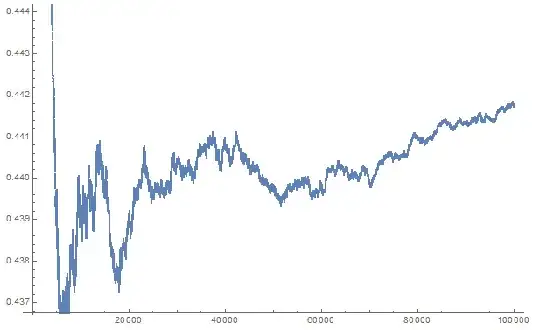

Let $\mathcal S=\{p\in\mathbb P|\exists m,n\in\mathbb Z_+:p=p_n+\cdots+p_{n+m}\}$. For "small" primes, not much greater than one million, it seems that about half of the primes belong to $\mathcal S$. But the greater primes the more combinations of consecutive primes available.

There are $\pi(p)$ primes less than or equal to $p$ and the number of available prime sequences is

$1\cdot\pi(p)+2\cdot(\pi(p)-1)+3(\pi(p)-2)+\cdots+(\pi(p)-1)\cdot 2=$

$\displaystyle\frac{\pi(p)^3+3\pi(p)^2+4\pi(p)}{6}$

(If I calculated it right).

I suppose it's possible to use the Prime Number Theorem to estimate the probability of $p\in\mathcal S$, but I'm pretty sure that I would mess it up.

My questions are:

Does $P(p\in\mathcal S)\to 1$ as $p\to\infty$?

Can it be proved that there is a maximal prime number not being a sum of consecutive primes?

See also How often is a sum of $k$ consecutive primes also prime? which is a similar but not an equivalent question.

This is what I got so far. It doesn't support my intuition, but I will let it run up to $10,000,000$ or more.