Define $V$ as a matrix whose columns are $v_i$, taken componentwise in the $e$-basis, and a matrix $Δ = I - V$. Then the elements of $Δ^TΔ$ are of the form of scalar products between all pairs of $(e_i - v_i)$, about which we know that

$$(e_i - v_i)\cdot(e_i - v_i) = \|e_i - v_i\|^2 < \frac1n,$$

$$|(e_i - v_i)\cdot(e_j - v_j)| \le \|e_i - v_i\|\cdot\|e_j - v_j\| < \frac1n.$$

That's interesting so let's use it!

We know our matrix $Δ^TΔ$ has elements which are never $\frac1n$ or more, and want to prove that $I-Δ$ is regular. A contradiction would be to find a normalized vector $x$ such that

$$x = Δ x.$$

If such vector exists then $x^TΔ^TΔx = \|Δx\|^2 = \|x\|^2 = 1$. Now proceed as

$$1 = \sum_{j,k}|x_j(Δ^TΔ)_{jk}x_k| \le \sum_{jk} |x_j| |(Δ^TΔ)_{jk}| |x_k| < \frac1n \sum_{jk} |x_j| |x_k|$$

(here I used triangle inequality and the fact we know about elements of $Δ^TΔ$, notice the strict $<$ between the two latter terms),

$$\frac1n \sum_{jk} |x_j| |x_k| = n\left(\frac{\sum_j |x_j|}{n}\right)^2 \le n \frac{\sum_j |x_j|^2}{n}$$

(inequality between arithmetic and quadratic mean, probably Cauchy-Schwartz if you rephrase it in a clever way), thus

$$1 < \sum_j |x_j|^2 = 1.$$

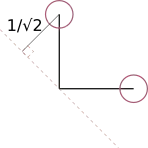

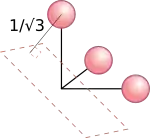

That's a contradiction, so that's our proof done. It also shows that the bound is tight: for $\|e_j - v_j\| \le 1/\sqrt n$ you could find a counterexample which saturates each of the $≤$'s (namely, $(e_j - v_j)_k = 1/n, \forall j \forall k$).