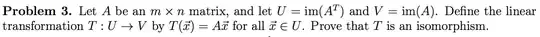

There may be some additional conceptual insights to be gained by proving this result WITHOUT using the fact that $rank(A) = rank(A^T)$. In fact, once the isomorphism result is established independently, it will immediately imply $rank(A) = rank(A^T)$, thereby yielding a conceptual proof of the latter.

We can establish isomorphism without assuming $rank(A) = rank(A^T)$ using basic properties of orthogonality and orthocomplementary subspaces. Let us assume that the entries in $A$ are real numbers (it will work on the complex field as well) so $\mbox{im}(A^T)$ and $\mbox{im}(A)$ are subspaces of $\mathbb{R}^n$ and $\mathbb{R}^m$, respectively. We will need to prove that $T(\vec{x}) = A\vec{x}$ is one-one and onto.

To prove that $T$ is onto, we will need to show that for any $\vec{y} \in \mbox{im}(A)$, there exists $\vec{x} \in \mbox{im}(A^T)$ such that $T(\vec{x}) = \vec{y}$. Since $\vec{y} \in \mbox{im}(A) \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m$, there exists $\vec{u} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ such that $\vec{y} = A\vec{u}$. We can write $\vec{u} = A^{T}\vec{z} + \vec{w}$ for some $\vec{z} \in \mathbb{R}^m$ and some $\vec{w} \in \mbox{im}(A^{T})^{\perp}$ making use of the orthogonal direct sum decomposition: $\mathbb{R}^n = \mbox{im}(A^{T}) \oplus \mbox{im}(A^{T})^{\perp}$ (note that $A^{T}\vec{z} \in \mbox{im}(A^T)$). Therefore, $\vec{y} = A\vec{u} = AA^{T}\vec{z} + A\vec{w}$. Furthermore, since $\vec{w} \in \mbox{im}(A^{T})^{\perp}$, it follows that $\vec{w}$ is orthogonal to each of the columns of $A^T$ or the rows of $A$ implying $A\vec{w} = \vec{0}$. This yields $\vec{y} = AA^{T}\vec{z} = A\vec{x}$, where $\vec{x} = A^T\vec{z} \in \mbox{im}(A^T)$. This proves that $T$ is onto.

That $T$ is one-one has been neatly proved in the earlier post by @symplectomorphic, but I include a slightly different presentation here for completeness. Suppose we are given that $T(\vec{x}_1) = T(\vec{x}_2)$ for $\vec{x}_1$ and $\vec{x}_2$ in $\mbox{im}(A^T)$. Let $\vec{u} = \vec{x}_1 - \vec{x}_2$ so $A\vec{u} = \vec{0}$. This means that $\vec{u}$ is orthogonal to the rows of $A$ (or columns of $A^T$) and, hence, to vectors in the linear span of columns of $A^T$. Therefore, $\vec{u} \in \mbox{im}(A^T)^{\perp}$. On the other hand, $\vec{u}$ itself resides in $\mbox{im}(A^T)$ because $\vec{x}_1$ and $\vec{x}_2$ are vectors in $\mbox{im}(A^T)$. Hence, $\vec{u}$ is orthogonal to itself, which means that $\vec{u} = \vec{0}$ and $\vec{x}_1 = \vec{x}_2$. Therefore, $T$ is one-one.

This completes the proof that $T$ is an isomorphism. One can easily deduce $rank(A) = rank(A^T)$ as a corollary of the above because isomorphic subspaces have the same dimension. In fact, they will carry any basis of its domain to a basis of its range. See this post:

The Pointer (https://math.stackexchange.com/users/356308/the-pointer), Proof that $f$ is an isomorphism if and only if $f$ carries a basis to a basis., URL (version: 2017-11-15): Proof that $f$ is an isomorphism if and only if $f$ carries a basis to a basis.