I think part of your original confusion is that your 'envelope' function is

too simple. Let's start (as in the crucial comment by @Ian)

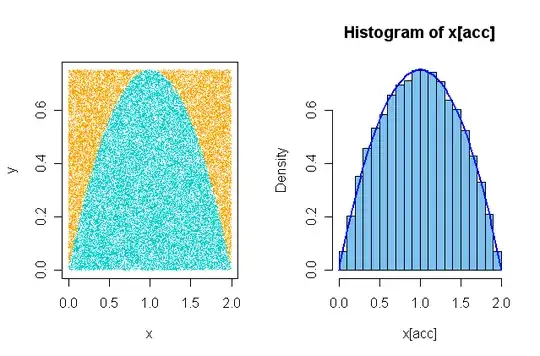

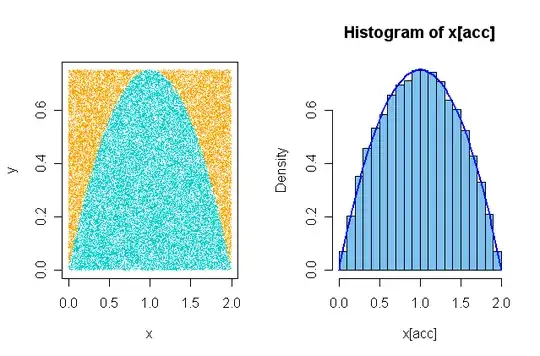

by generating points uniformly in the rectangle that encloses your PDF

$f(x) = 0.75(2x - x^2),$ for $x \in [0,2].$ Points (blue) that fall under

the PDF curve are accepted and those above it (orange) are rejected.

A histogram of the accepted x-values fits the PDF well. You can

verify by integration that the simulated values of $E(X)$ and $SD(X)$

are correct within simulation error. (My R code below, saves all

points and then settles which ones are accepted at the end.)

B = 40000; M = 3/4

x = runif(B, 0, 2); y = runif(B, 0, M)

acc = y <= M*(2*x - x^2)

mean(x[acc]); sd(x[acc])

## 1.002849 # Simulated E(X)

## 0.446792 # Simulated SD(X)

par(mfrow = c(1,2)) # side-by-side plots

plot(x, y, pch=".", col="red")

points(x[acc], y[acc], pch=".")

hist(x[acc], prob=T, col="wheat")

curve(.75*(2*x - x^2), 0, 2, lwd=2, col="blue", add=T)

par(mfrow = c(1,1)) # restore default plotting

In practice, it often 'wastes' too many candidate values to

simulate within a rectangle, so an 'envelope' function is chosen

for the upper boundary.

In your more general notation, the envelope function is $M$ times the

density function of $Unif(0, 2)$. It may help you to remember how

this method works if you rewrite my code in your more general

notation.

Notes: (a) Your PDF is the density function of $X$ where $X = 2U$ and $U \sim Beta(2,2).$ In R, you could simulate this distribution

using 2*rbeta(B, 2, 2) where the random sampling function rbeta is built into R.

w = rbeta(100000, 2, 2)

mean(2*w); sd(2*w)

## 1.001450 # Compare with simulated mean and SD above

## 0.4466403

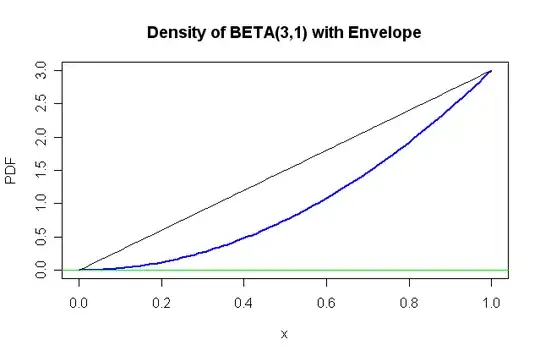

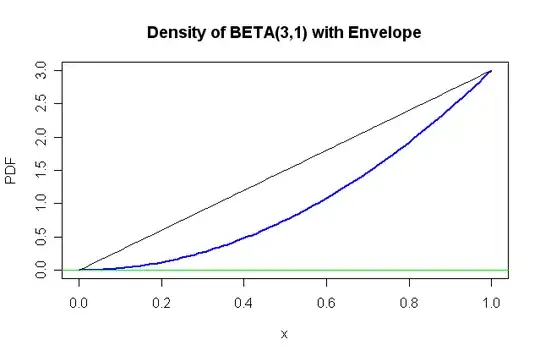

(b) If you wanted to sample from $Beta(3,1)$

using the rejection method, there is a natural nontrivial envelope: you could use the envelope function $3x$ which

can be considered a multiple of the triangular density function

of $Beta(2,1).$ (It is easy to simulate observations from $Beta(2,1)$ using the inverse CDF method and the envelope is 'close enough'

that only a small proportion of candidate values will be rejected.)