A few examples of calculation of smoothed min-entropy:

(Non-degenerate distribution, small $\epsilon$)

Consider a generic discrete probability distribution whose maximum is strictly larger than the other values. We can assume without loss of generality that the probabilities are arranged in non-increasing order, so that we have

$$P_{\rm max}\equiv\max_x P_x = P_1 > P_2 \ge P_3 \ge \cdots$$

The min-entropy is in this case

$$H_{\rm min}(X)_P\equiv H_{\infty}(X)_P \equiv \log \frac{1}{P_{\rm max}}.$$

On the other hand, for small enough $\epsilon>0$ (or more specifically, for $\epsilon<P_{\rm max}-P_2$), the smoothed min-entropy will be

$$H_{\rm min}^\epsilon(X)_P = \log\left( \frac{1}{P_{\rm max}-\epsilon}\right).$$

The idea is simple: we "steal" probability from the maximum probability event, in order to decrease the maximum probability of the distribution. As long as $\epsilon$, the amount we're stealing is small enough, then the most likely event does not change, and we get this result.

(Non-degenerate distribution, not-so-small $\epsilon$)

If, on the other hand, $\epsilon$ starts being large enough that the most likely event changes, then we get a different values for the smoothed min-entropy. The next simplest such example we can consider is when $\epsilon$ is large enough to lower $P_{\rm max}$ to the height of $P_2$, but not large enough to also lower $P_{\rm max}$ and $P_2$ to the height of $P_3$. More precisely, this amounts to the conditions:

$$\epsilon>P_{\rm max}-P_2,

\qquad P_2>P_3,

\qquad \epsilon< (P_{\rm max}-P_2) + 2(P_2-P_3).$$

In such cases, we get

$$H_{\rm min}^\epsilon(X)_P = \log\left(\frac{1}{P_2 - \left(\frac{\epsilon-(P_{\rm max}-P_2)}{2}\right) }\right)

= \log \left(\frac{2}{P_{\rm max}+P_2 - \epsilon}\right).$$

The first expression in the logarithm is derived by gradually removing probability first from $P_{\rm max}$, and then from $P_{\rm max}$ and $P_2$ together: $\epsilon-(P_{\rm max}-P_2)$ is how much probability we have to remove after having $P_{\rm max}=P_2$, and we then decrease both $P_{\rm max}$ and $P_2$ together, but at a halved rate (because we have to decrease them both together, so the "cost" is doubled).

(Degenerate most likely events)

Suppose now that $P_1=P_2=\cdots P_n> P_{n+1}\ge ...$ In this scenario, for $\epsilon$ small enough, we reduce all of the most likely events at the same time. Therefore the smoothed min-entropy becomes

$$H_{\rm min}^\epsilon(X)_P = \log\left(\frac{1}{P_{\rm max} - \epsilon/n}\right).$$

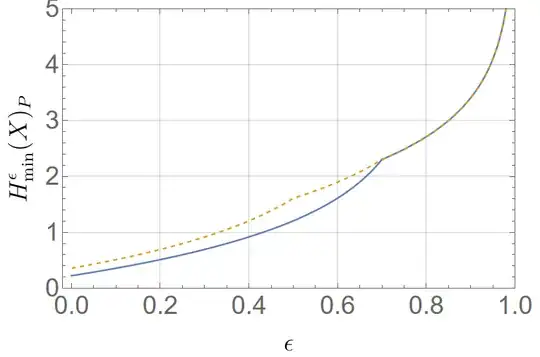

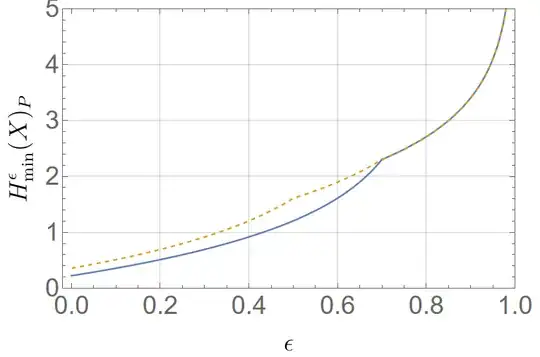

(More explicit examples)

- Consider $P_1 = 0.7, P_2=0.2, P_3=0.1$. Then

$$H_{\rm min}^\epsilon(X)_P = \begin{cases}\log\left(\frac{1}{0.7-\epsilon}\right) & \epsilon \le 0.5, \\

\log\left(\frac{1}{0.2 - (\epsilon-0.5)/2}\right), & 0.5\le \epsilon\le 0.7, \\

\log\left(\frac{1}{0.1 - (\epsilon-0.7)/3}\right), & 0.7\le \epsilon\le 1

\end{cases}.$$

- Another example, where this time the two least likely even have the same probability, is $P_1 = 0.8, P_2=0.1, P_3=0.1$. In this case, we have

$$H_{\rm min}^\epsilon(X)_P = \begin{cases}\log\left(\frac{1}{0.8-\epsilon}\right) & \epsilon \le 0.7, \\

\log\left(\frac{1}{0.1 - (\epsilon-0.7)/3}\right), & 0.7\le \epsilon\le 1

\end{cases}.$$

Note how $H_{\rm min}^\epsilon(X)_P$ is always continuous, but not smooth, with respect to $\epsilon$.

More specifically, here is what the two smoother min-entropies look like as a function of $\epsilon$:

Here, the dashed orange line corresponds to the first example, while the solid blue line to the second one.