In linear regression overfitting occurs when the model is "too complex". This usually happens when there are a large number of parameters compared to the number of observations. Such a model will not generalise well to new data. That is, it will perform well on training data, but poorly on test data.

A simple simulation can show this. Here I use R:

> set.seed(2)

> N <- 4

> X <- 1:N

> Y <- X + rnorm(N, 0, 1)

>

> (m0 <- lm(Y ~ X)) %>% summary()

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -0.2393 1.8568 -0.129 0.909

X 1.0703 0.6780 1.579 0.255

Residual standard error: 1.516 on 2 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.5548, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3321

F-statistic: 2.492 on 1 and 2 DF, p-value: 0.2552

Note that we obtain a good estimate of the true value for the coefficient of X. Note the Adjusted R-squared of 0.3321 which is an indication of the model fit.

Now we fit a quadratic model:

> (m1 <- lm(Y ~ X + I(X^2) )) %>% summary()

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -4.9893 2.7654 -1.804 0.322

X 5.8202 2.5228 2.307 0.260

I(X^2) -0.9500 0.4967 -1.913 0.307

Residual standard error: 0.9934 on 1 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9044, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7133

F-statistic: 4.731 on 2 and 1 DF, p-value: 0.3092

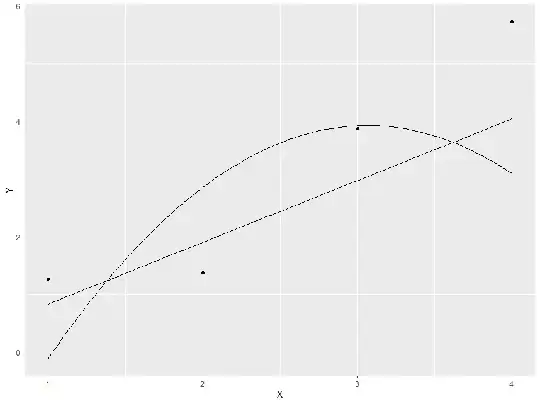

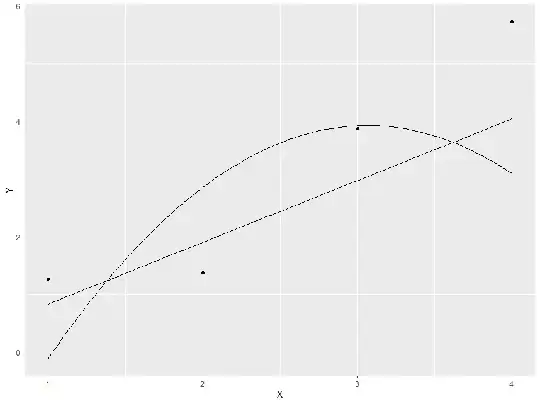

Now we have a much higher Adjusted R-squared: 0.7133 which may lead us to think that the model is much better. Indeed if we plot the data and the predicted valus from both models we get :

> fun.linear <- function(x) { coef(m0)[1] + coef(m0)[2] * x }

> fun.quadratic <- function(x) { coef(m1)[1] + coef(m1)[2] * x + coef(m1)[3] * x^2}

>

> ggplot(data.frame(X,Y), aes(y = Y, x = X)) + geom_point() + stat_function(fun = fun.linear) + stat_function(fun = fun.quadratic)

So on the face of it, the quadratic model looks much better.

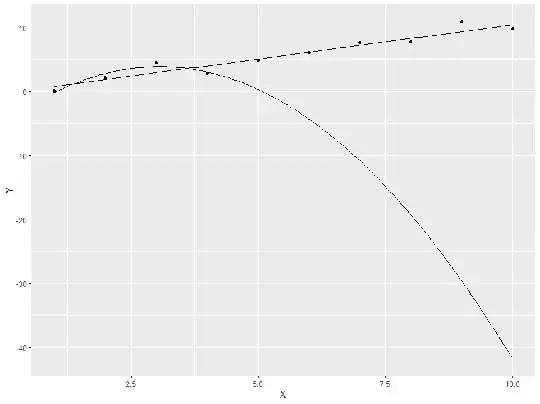

Now, if we simulate new data, but use the same model to plot the predictions, we get

> set.seed(6)

> N <- 4

> X <- 1:N

> Y <- X + rnorm(N, 0, 1)

> ggplot(data.frame(X,Y), aes(y = Y, x = X)) + geom_point() + stat_function(fun = fun.linear) + stat_function(fun = fun.quadratic)

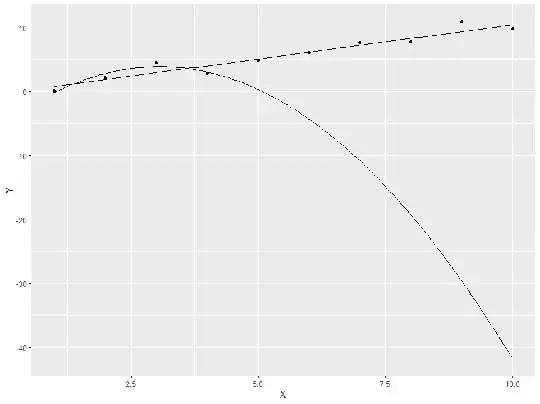

Clearly the quadratic model is not doing well, whereas the linear model is still reasonable. However, if we simulate more data with an extended range, using the original seed, so that the initial data points are the same as in the first simulation we find:

> set.seed(2)

> N <- 10

> X <- 1:N

> Y <- X + rnorm(N, 0, 1)

> ggplot(data.frame(X,Y), aes(y = Y, x = X)) + geom_point() + stat_function(fun = fun.linear) + stat_function(fun = fun.quadratic)

Clearly the linear model still performs well, but the quadratic model is hopeless outside the orriginal range. This is because when we fitted the models, we had too many parameters (3) compared to the number of observations (4).

Edit: To address the query in the comments to this answer, about a model that does not include higher order terms.

The situation is the same: If the number of parameters approaches the number of observations, the model will be overfitted. With no higher order terms, this will occur when the number of variables / features in the model approaches the number of observations.

Again we can demonstrate this easily with a simulation:

Here we simulate random data data from a normal distribution, such that we have 7 observations and 5 variables / features:

> set.seed(1)

> n.var <- 5

> n.obs <- 7

>

> dt <- as.data.frame(matrix(rnorm(n.var * n.obs), ncol = n.var))

> dt$Y <- rnorm(nrow(dt))

>

> lm(Y ~ . , dt) %>% summary()

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -0.6607 0.2337 -2.827 0.216

V1 0.6999 0.1562 4.481 0.140

V2 -0.4751 0.3068 -1.549 0.365

V3 1.2683 0.3423 3.705 0.168

V4 0.3070 0.2823 1.087 0.473

V5 1.2154 0.3687 3.297 0.187

Residual standard error: 0.2227 on 1 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9771, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8627

We obtain an adjusted R-squared of 0.86 which indicates excellent model fit. On purely random data. The model is severely overfitted. By comparison if we double the number of obervations to 14:

> set.seed(1)

> n.var <- 5

> n.obs <- 14

> dt <- as.data.frame(matrix(rnorm(n.var * n.obs), ncol = n.var))

> dt$Y <- rnorm(nrow(dt))

> lm(Y ~ . , dt) %>% summary()

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -0.10391 0.23512 -0.442 0.6702

V1 -0.62357 0.32421 -1.923 0.0906 .

V2 0.39835 0.27693 1.438 0.1883

V3 -0.02789 0.31347 -0.089 0.9313

V4 -0.30869 0.30628 -1.008 0.3430

V5 -0.38959 0.20767 -1.876 0.0975 .

Signif. codes: 0 ‘*’ 0.001 ‘’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 0.7376 on 8 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.4074, Adjusted R-squared: 0.03707

F-statistic: 1.1 on 5 and 8 DF, p-value: 0.4296

..adjusted R squared drops to just 0.037