I have been working on dynamic programming for some time. The canonical way to evaluate a dynamic programming recursion is by creating a table of all necessary values and filling it row by row. See for example Cormen, Leiserson et al: "Introduction to Algorithms" for an introduction.

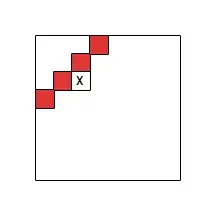

I focus on the table-based computation scheme in two dimensions (row-by-row filling) and investigate the structure of cell dependencies, i.e. which cells need to be done before another can be computed. We denote with $\Gamma(\mathbf{i})$ the set of indices of cells the cell $\mathbf{i}$ depends on. Note that $\Gamma$ needs to be cycle-free.

I abstract from the actual function that is computed and concentrate on its recursive structure. Formally, I consider a recurrrence $d$ to be dynamic programming if it has the form

$\qquad d(\mathbf{i}) = f(\mathbf{i}, \widetilde{\Gamma}_d(\mathbf{i}))$

with $\mathbf{i} \in [0\dots m] \times [0\dots n]$, $\widetilde{\Gamma}_d(\mathbf{i}) = \{(\mathbf{j},d(\mathbf{j})) \mid \mathbf{j} \in \Gamma_d(\mathbf{i}) \}$ and $f$ some (computable) function that does not use $d$ other than via $\widetilde{\Gamma}_d$.

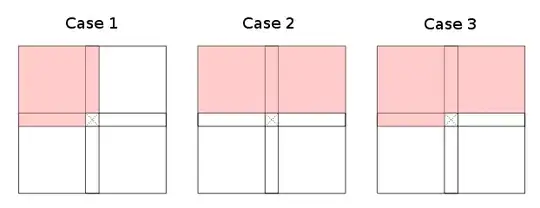

When restricting the granularity of $\Gamma_d$ to rough areas (to the left, top-left, top, top-right, ... of the current cell) one observes that there are essentially three cases (up to symmetries and rotation) of valid dynamic programming recursions that inform how the table can be filled:

The red areas denote (overapproximations of) $\Gamma$. Cases one and two admit subsets, case three is the worst case (up to index transformation). Note that it is not strictly required that the whole red areas are covered by $\Gamma$; some cells in every red part of the table are sufficient to paint it red. White areas are explictly required to not contain any required cells.

Examples for case one are edit distance and longest common subsequence, case two applies to Bellman & Ford and CYK. Less obvious examples include such that work on the diagonals rather than rows (or columns) as they can be rotated to fit the proposed cases; see Joe's answer for an example.

I have no (natural) example for case three, though! So my question is: What are examples for case three dynamic programming recursions/problems?