I'm sorry for this hardly understandable caption - I could not make up a better one.

I am trying to learn assembly (AT&T) and have a question about registers:

Are register-names each accessing completely different and independent memory? Or do they give access to specific smaller parts of one register and therefore address the same memory?

e.g.: Is al addressing the lowest 8 bits of ax, eax & rax, so that modifying ah modifies bit 9-16 of ax, eax & rax ? Or are ah, al, ax, eax & rax all different independent registers ?

Thanks in advance

Moritz

- 328,167

- 45

- 605

- 847

- 59

- 1

- 1

- 8

3 Answers

Just to be clear: registers do no reside in memory and do not have an address.

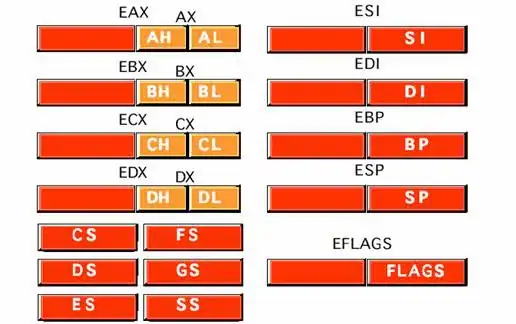

Yes, the AX is the lower 16 bits of the EAX register. AH and AL are the higher and lower 8 bits from AX. This is all a single register with different names for different ways to access it. This is for x86:

Image from: http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CPU/x86/lecture.html#X77_0070_gp_registers

- 8,183

- 25

- 43

-

Thank you for the nice explanation and Image. Can you tell wether this applies to x86_64 RAX (etc..) registers too? – Moritz Petersen Nov 03 '13 at 13:28

-

1@MoritzPetersen yes, it applies to the 64-bit registers as well – jalf Nov 03 '13 at 13:47

Registers use some type of electronic cycles called flip-flops, a flip-flop is a cycle that stores 0 or 1 and keeps it stored. An N size register is a block of N flip-flops. The flip-flop looks like this:

- clock: is a trigger that when it activated the data is passed, so no data, 0 or 1, is stored by ascendent. It's controlled by the control unit in the CPU.

- input: is a input for 1 bit, tiny wire, stores either 0 or 1 in the flip-flop.

- output: is output where you can read the data.

In a 32 bit register, 32 of these are aligned in one block with 32 bit input and 32 bit output:

notice, in this register there is no sub-registers, like eax, ax, ah, al. I guess Intel guys had to use 4 bit clock rather than 1 as:

- First clock, activates all the 32 bit flip-flops,

eax. - Second clock, activates only the lower 16 bit flip-flops,

ax. - Third clock, activates only the second 8 bit,

ah. - Fourth clock, activates only the first 8 bit,

al.

something like (8 FF, 8 flip-flops, and the dots means the line is connected there):

now when the processor decodes the instructions, it can tell which instruction you want and which register you target, which clock to trigger, using the opcode of the instruction:

[b0] ff mov $0xff, %al

[b4] ff mov $0xff, %ah

[66 b8] ff ff mov $0xffff, %ax

[b8] ff ff ff ff mov $0xffffffff, %eax

The realty might be different, but the principle is the same. You can read more about this stuff in any logic-design or computer architecture book, but you don't need to it to start program in assembly, but it will help you to understand how stuff works.

-

Thank you - that makes it even more understandable. Does memory work the same way ? – Moritz Petersen Nov 03 '13 at 16:10

-

@MoritzPetersen Not exactly, generally memory has input port for the address to write data into the bit cells, output for read and clocks for read and write, there are many types of memory each is deferent in the way bits are stored the memory cells, you can look for *memory arrays* or have a look at the memory arrays section in this [slides](https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxkcmFib3VlbG1hYXR5fGd4OjFiMWI5MGYyNDBkZjE3N2M) from a class I had, it helped me a lot. – Nov 03 '13 at 17:10

In addition to the overlap between parts of general purpose registers, the mm registers alias the x87 stack, and xmm registers overlap ymm registers (where applicable).

- 9,167

- 1

- 21

- 23