This is a question I was inspired to ask based on this question, which notes that quantum annealing is an entirely different model for computation than the usual circuit model. I've heard this before, and it's my understanding that the gate-model does not apply to quantum-annealing, but I've never quite understood why that is, or how to parse the computations that an annealer can do. As I understand from several talks (some by D-wave themselves!) the fact that the annealers are confined to a specific Hamiltonian plays into it.

2 Answers

A Quantum Annealer, such as a D-Wave machine is a physical representation of the Ising model and as such has a 'problem' Hamiltonian of the form $$H_P = \sum_{J=1}^nh_j\sigma_j^z + \sum_{i, j}J_{ij}\sigma_i^z\sigma_j^z.$$

Essentially, the problem to be solved is mapped to the above Hamiltonian. The system starts with the Hamiltonian $H_I = \sum_{J=1}^nh'_j\sigma_j^x$ and the annealing parameter, $s$ is used to map the initial Hamiltonian $H_I$ to the problem Hamiltonian $H_P$ using $H\left(s\right) = \left(1-s\right)H_I + sH_P$.

As this is an anneal, the process is done slowly enough to stay near the ground state of the system while the Hamiltonian is varied to that of the problem, using tunnelling to stay near the ground state as described in Nat's answer.

Now, why can't this be used to describe a gate model QC? The above is a Quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO) problem, which is NP-hard... Indeed, here's an article mapping a number of NP problems to the Ising model. Any problem in NP can be mapped to any NP-hard problem in polynomial time and integer factorisation is indeed an NP problem.

Well, the temperature is non-zero, so it's not going to be in the ground state throughout the anneal and as a result, the solution is still only an approximate one. Or, in different terms, the probability of failure is greater than a half (it's nowhere near having a decent probability of success compared with what a universal QC considers 'decent' - judging from graphs I've seen, the probability of success for the current machine is around $0.2\%$ and this will only get worse with increasing size), and the anneal algorithm is not bounded error. At all. As such, there's no way of knowing whether or not you've got the correct solution with something such as integer factorisation.

What it (in principle) does is get very close to the exact result, very quickly, but this doesn't help for anything where the exact result is required as going from 'nearly correct' to 'correct' is still an extremely difficult (i.e. presumably still NP in general, when the original problem is in NP) problem in this case, as the parameters that are/give a 'nearly correct' solution aren't necessarily going to be distributed anywhere near the parameters that are/give the correct solution.

Edit for clarification: what this means is that a quantum annealer (QA) still takes exponential time (albeit potentially a faster exponential time) to solve NP problems such as integer factorisation, where a universal QC gives an exponential speed up and can solve the same problem in poly time. This is what implies a QA cannot simulate a universal QC in poly time (otherwise it could solve problems in poly time that it can't). As pointed out in the comments, this is not the same as saying that a QA cannot give the same speedup in other problems, such as database search.

- 3,816

- 3

- 24

- 45

Annealing's more of an analog tactic.

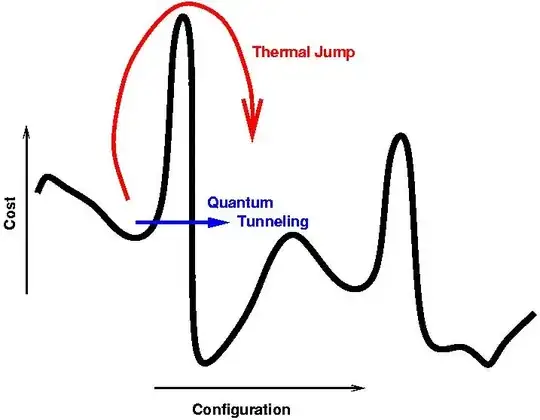

The gist is that you have some weird function that you want to optimize. So, you bounce around it. At first, the "temperature" is very high, such that the selected point can bounce around a lot. Then as the algorithm "cools", the temperature goes down, and the bouncing becomes less aggressive.

Ultimately, it settles down to a local optima which, ideally, is favorably like the global optima.

Here's an animation for simulated annealing (non-quantum):

But, it's pretty much the same concept for quantum annealing:

By contrast, gate-logic is far more digital than analog. It's concerned with qubits and logical operations rather than merely finding a result after chaotic bouncing-around.

- 1,497

- 1

- 14

- 27