(By request of the OP.)

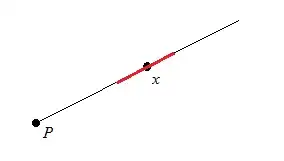

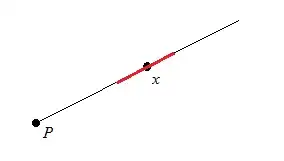

If $x$ is a point different from $P$, and $\epsilon\le\|x-P\|$, the $\epsilon$-ball centred at $x$ is an open interval of length $2\epsilon$ centred at $x$ on the line $\overline{Px}$:

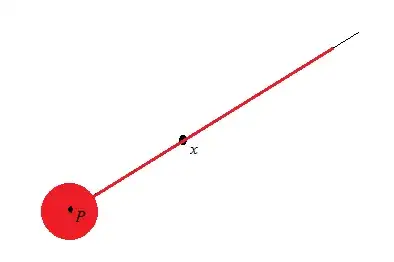

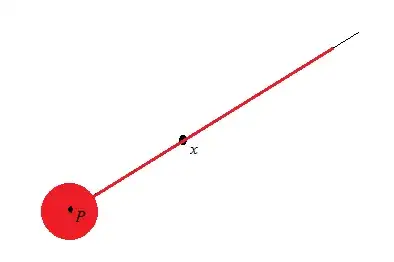

If $\epsilon>\|x-P\|$, the $\epsilon$-ball at $x$ consists of the segment $\overline{Px}$, the open ray of length $\epsilon$ extending from $x$ away from $P$ on the line $\overline{Px}$, and the ordinary open ball of radius $\epsilon-\|x-P\|$ centred at $P$:

In other words, in every case it contains all of the points that are less than $\epsilon$ away from $x$ provided that you can move only along lines passing through $P$. You must always be moving directly towards or directly away from $P$.

Finally, the $\epsilon$-ball at $P$ is just the ordinary Euclidean $\epsilon$-ball at $P$.

For the triangle inequality, let $x,y$, and $z$ be any three points; we wish to show that $$d(x,y)\le d(x,z)+d(z,y)\;.$$

Consider first the case in which $x,y$, and $P$ are collinear. If $z$ is also on this line, $d$ reduces to the usual Euclidean metric, so assume that this is not the case. Then $d(x,z)=\|x-P\|+\|P-z\|$, $d(z,y)=\|z-P\|+\|P-y\|$, and $d(x,y)\le\|x-P\|+\|P-y\|$ by the triangle inequality for the Euclidean metric, so

$$\begin{align*}

d(x,y)&\le\|x-P\|+\|P-y\|\\

&\le\big(\|x-P\|+\|P-z\|\big)+\big(\|z-P\|+\|P-y\|\big)\\

&=d(x,z)+d(z,y)\;.

\end{align*}$$

Now assume that $x,y$, and $P$ are not collinear, so that $d(x,y)=\|x-P\|+\|P-y\|$. If $z$ is not on either of the lines $\overline{Px}$ and $\overline{Py}$, then

$$\begin{align*}

d(x,y)&=\|x-P\|+\|P-y\|\\

&<\big(\|x-P\|+\|P-z\|\big)+\big(\|z-P\|+\|P-y\|\big)\\

&=d(x,z)+d(z,y)\;.

\end{align*}$$

If $z$ is on one of those lines, we may assume without loss of generality that it’s on $\overline{Px}$. Then $\|x-P\|\le\|x-z\|+\|z-P\|$ by the triangle inequality for the Euclidean metric, so

$$\begin{align*}

d(x,y)&=\|x-P\|+\|P-y\|\\

&\le\big(\|x-z\|+\|z-P\|\big)+\|P-y\|\\

&=\|x-z\|+\big(\|z-P\|+\|P-y\|\big)\\

&=d(x,z)+d(z,y)\;.

\end{align*}$$