About the question regarding the purported absence of symbols for formulae (or statements) :

but there is no symbols for formulas or sentences in first order logic. Does the book miss it?

we have to note that the "basic convention" (alas! left implicit in Kaye's book) is that lower case letters from Greek alphabet are meta-variables (i.e. variables in the meta-language) standing for formulae of the propositional and first-order languages, while upper case letters stand for set of formulae (see page 65 : a "derivation from assumptions $Σ ⊆ BT(X)$ is a derivation of finite length where each statement in it is an element of $BT(X)$ and which uses only the following proof rules [...]").

Please, note that in the propositional logic, formulae are called boolean terms, and $BT(X)$ is the name of the set of boolean terms over the set $X$ of propositional letters [see page 64].

See also page 119 for the :

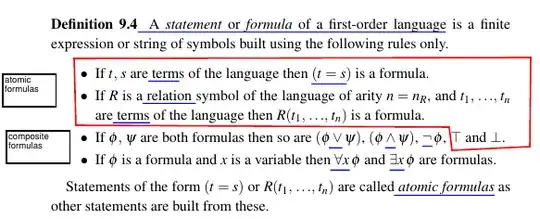

Definition 9.4 : A statement or formula of a first-order language is [...]

and see page 120 :

Definition 9.6 A formula $σ$ is closed or is a sentence if every occurrence of

every variable $x$ in it is in the scope of a matching quantifier [...].

Thus, a sentence is a (closed) formula and we use the same symbols (lower case Greek letters) for them.

Compare with Dirk van Dalen, Logic and Structure (5th ed - 2013), page 7, where the "basic convention" is made explicit :

Definition 2.1.2 The set $PROP$ of propositions is the smallest set $X$ with the properties :

(i) $p_i \in X (i \in \mathbb N), \bot \in X$,

<p><em>(ii)</em> if $ϕ,ψ \in X$, then $(ϕ ∧ ψ), (ϕ ∨ ψ), (ϕ→ψ), (ϕ↔ψ) \in X$,</p>

<p><em>(iii)</em> if $ϕ \in X$ then $(¬ϕ) \in X$.</p>

[...]

A warning to the reader is in order here. We have used Greek letters $ϕ,ψ$ in the

definition; are they propositions? Clearly we did not intend them to be so, as we want

only those strings of symbols obtained by combining symbols of the alphabet in a

correct way. Evidently no Greek letters come in at all! The explanation is that $ϕ$ and

$ψ$ are used as variables for propositions. Since we want to study logic, we must use

a language in which to discuss it. As a rule this language is plain, everyday English.

We call the language used to discuss logic our meta-language and $ϕ$ and $ψ$ are metavariables for propositions. We could do without meta-variables by handling (ii) and

(iii) verbally: if two propositions are given, then a new proposition is obtained by

placing the connective $∧$ between them and by adding brackets in front and at the

end, etc. This verbal version should suffice to convince the reader of the advantage

of the mathematical machinery.

\xiis $\xi$ (and notksi), you're looking for\psiwhich is $\psi$. – Asaf Karagila Jul 23 '14 at 21:22