The intuition for the (second) fundamental theorem of calculus is that

\begin{equation}

\text{"the total change is the sum of all the little changes".}

\end{equation}

The total change is $g(b) - g(a)$. The little changes are

\begin{equation*}

g(t_i) - g(t_{i-1}) \approx g'(\xi_i)(t_i - t_{i-1})

\end{equation*} (where $\xi_i$ is any point in $[t_{i-1},t_i]$.)

By adding up all the little changes, you get the total change.

\begin{align*}

g(b) - g(a) &= \sum g(t_i) - g(t_{i-1}) \\

&\approx \sum g'(\xi_i)(t_i - t_{i-1}).

\end{align*}

Notice that this last expression is a Riemann sum for the integral $\int_a^b g'(t) \, dt$.

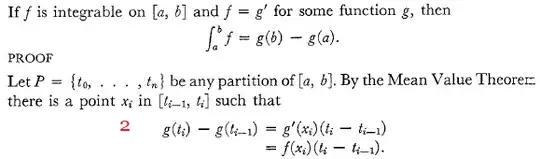

It's wonderful that the mean value theorem allows us to replace the approximate equalities with exact equalities, which helps us turn this intuitive argument into a rigorous proof.