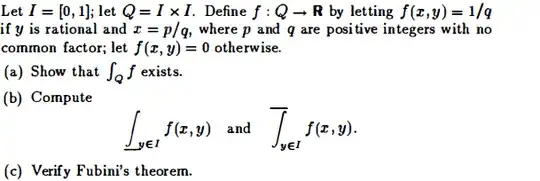

In what follows, $p$ and $q$ will denote positive integers with no common factor, $r,s$ will be rational numbers, $i$ will be an irrational number, and $x,y,z$ will be arbitrary real numbers.

The function is defined by $f(\frac pq,r)=\frac 1q$, $f=0$ otherwise. I claim that $f$ is discontinuous on the points $a$ which have a rational first coordinate and continuous on the points $b$ which have an irrational first coordinate.

Discontinuity. Fix $p$ and $q$ and suppose the point is of the form $a=(\frac pq,y),$ for some real $y$. In any neighborhood of $a$ there are points of the form $(\frac pq,r)$ and $(\frac pq,i)$. It follows that in any neighborhood of $a$ the function takes the values $f(\frac pq,r)=\frac 1q$ and $f(\frac pq,i)=0$, so $\lim_{(x,y)\to a} f(x,y)$ doesn't exist.

Continuity. Now suppose $b=(i,y)$ for some real $y$, so that $f(b)=0$, and let $g(u)$ be Thomae's function. $g(u)$ is continuous at the irrationals $i$, so we know that given a positive $\epsilon$ there exists some positive $\delta$ such that, whenever $|i-u|<\delta$, $|g(u)|<\epsilon$.

Now, take that same $\delta$. If $|(i,y)-(u,v)|<\delta$, then in particular $|i-u|<\delta$. There are two possibilities: either $f(u,v)=0$ or $f(u,v)=g(u)$. In either case, following the property of $\delta$, $|f(u,v)|<\epsilon$, so that $f$ is continuous at these points.

What I tried to say in the comments, intuitively, is that in any neighborhood of $b$ you will find points which map to $0$ and points which map to $\frac 1q$ for some $q$, but as the first coordinate inevitably approaches an irrational number, those values of $q$ will be forced to approach infinity. I hope that the argument presented made this intuition clear.

Finally, the segments $S_r=\{(r,y): 0\leq y\leq 1\}=\{r\}\times [0,1]$ have product measure $0\cdot 1=0$, so that the set of points of discontinuity $\cup_{r\in \mathbb Q} S_r$ has measure $0$.