Sangaku (算額) are Japanese geometric puzzles written on wooden tablets over 150 years ago. There have been several previous puzzles, but I didn't see this one.

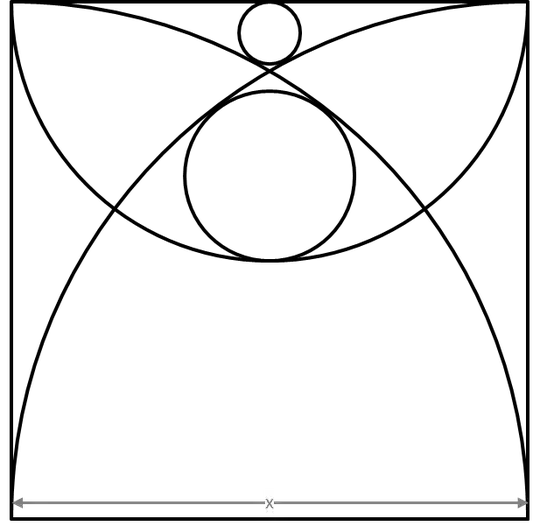

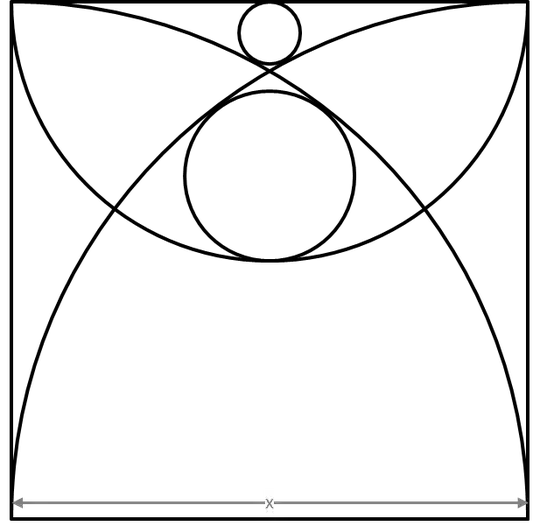

Find the radii of the two inner circles in terms of $x$:

Sangaku (算額) are Japanese geometric puzzles written on wooden tablets over 150 years ago. There have been several previous puzzles, but I didn't see this one.

Find the radii of the two inner circles in terms of $x$:

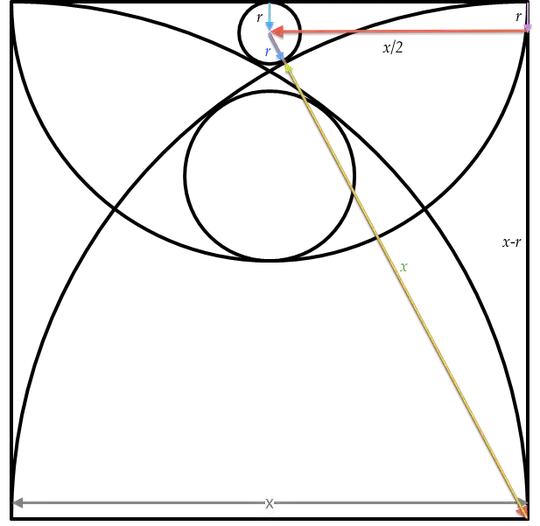

Let the radius of the smaller circle be $r$, and the larger be $R$. It is immediately obvious that $r$ satisfies $$(x-r)^2 + (x/2)^2 = (r+x)^2,$$ and $R$ satisfies $$(x/2+R)^2 + (x/2)^2 = (x-R)^2.$$ The solutions of these are a straightforward algebraic exercise.

Slightly less trivial would be finding the radius of the circle inscribed in either of the two "ear-shaped" regions (inside the semicircle and one of the two quarter circles, but outside the other quarter circle). However, it too is amenable to the same solving technique.

Addendum. Since an image was requested, I have attached it below:  The horizontal red line has length $x/2$, and the diagonal line has length $r+x$, since it joins the centers of two tangent circles with radius $r$ (blue) and $x$ (green/yellow). The third side is simply $x - r$, because the red horizontal line is parallel to the top edge of the square.

The horizontal red line has length $x/2$, and the diagonal line has length $r+x$, since it joins the centers of two tangent circles with radius $r$ (blue) and $x$ (green/yellow). The third side is simply $x - r$, because the red horizontal line is parallel to the top edge of the square.

An analogous procedure for the larger circle results in the second equation. It really does not get any easier than that.