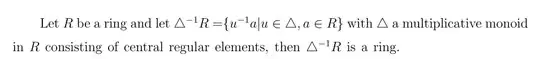

This notation refers to a noncommutative ring of fractions. The construction is analogous to the commutative case, but certain conditions have to be met.

A subset $S$ of a ring $R$ needs to satisfy the Ore conditions in order for the analogous construction to take place. Here in particular, the submonoid $\Delta$ of $R$ consisting of central regular elements does indeed satisfy the (left and right) Ore conditions.

The construction proceeds by forming all pairs $(r,s)$ with $r\in R$ and $s\in \Delta$, and then making an equivalence relation on them that forms a ring. The fact that the elements are central and regular comes into play when showing that the addition and multiplication are well-defined. The set of equivalence classes using these operations is a new ring $\Delta^{-1}R$. Verifying this elementarily is complicated, so I would prefer to refer you to the reference at the end.

how to understand the invertible element of u?

These pairs $(r,s)$ are thought of as "fractions" with denominator $s$. Normally we would have to be careful to say whether this was a left or right ring of fractions, but since elements of $\Delta$ are central, it turns out not to matter. Anyhow, after you start thinking of the equivalence class of $(r,s)$ as a fraction, then the notations $\frac{r}{s}=s^{-1}r$ starts to make sense.

So each $s\in\Delta$ is not necessarily a unit in $R$, but it is a unit in $\Delta^{-1}R$, having inverse $(1,s)=\frac{1}{s}$.

Moreover, is the product of a regular element and a unit also a unit?

All of the elements of $\Delta$ become units in $\Delta^{-1}R$, and of course all of the units of $R$ stay units in $\Delta^{-1}R$. In principle it is possible for a regular element $x$ of $R$ to remain noninvertible in $\Delta^{-1}R$, and since the group of units of any ring is closed under multiplication, it is possible for $xu$ to be a nonunit.

For a good introduction to this (assuming you're comfortable with the commutative ring of quotients) definitely check out Lectures on modules and rings by T.Y. Lam, specifically section 10A: "Ore localizations."