On page 90 of Visual Group Theory by Nathan Carter, there's an exercise (Exercise 5.20) that points out an interesting phenomenon: some small groups belong to more than one of the classical group families — cyclic $C_n$, dihedral $D_n$, symmetric $S_n$, and alternating $A_n$ — when considered up to isomorphism.

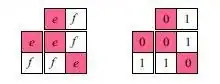

For example, the book notes that $D_1$, a degenerate dihedral group with two elements, has the same group structure as the cyclic group $C_2$. Their multiplication tables match, modulo the names of the elements.

My Question

What other small groups (say, with order $\leq 12$) are shared across these families in the sense that they are isomorphic? Are there, for example, any groups in the $D_n$ family that are isomorphic to a group in $S_n$, $A_n$, or $C_n$?

I'm trying to build intuition for recognizing structural similarities between groups that arise in different contexts, and I’m curious about how frequently this overlap occurs among these well-known families.