I have been practicing my residue calculus recently (a fairly new topic for me), I started with calculating integrals of simple functions in the form of

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(x^2 + 1)^n} \, dx$$

where $n$ is an integer $>0$. I used a semicircular contour over the top half of the complex plane with the diameter of this contour covering the real axis. It is not that difficult to prove that the circumference part of such contour will be $0$ as $R$ tends to infinity. So I will not spend time on this here and focus on the real part of the contour.

I used these formulas from Cauchy Residue Theorem

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(x^2 + 1)^n} \, dx = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{Res}(f,i)$$

and

$$\operatorname{Res}(f, i) = \frac{1}{(n-1)!} \lim_{x \to i} \frac{d^{n-1}}{dx^{n-1}} \left[ (x - i)^n f(x) \right]$$

I did not use the sum in the first formula since there is only one special point in those kinds of integrals and therefore only one residue.

Out of curiosity, I decided to try using this formula for cases that $n$ is a non-integer. I tried $1.5$, then a bunch of half integers ($2.5$ through $5.5$), then $1.6$ and then a general formula for any $n>0.5$, as if $n$ is less than or equal to $0.5$ then the integral obviously diverges.

The $\frac{1}{(n-1)!}$ part of the formula is easy to extend into non-integers using the gamma function. The problem arises when defining a non-integer order derivative. I tried generalising it from differentiating a function in the form $(x + a)^n$.

If you only use positive integers it is easy to see that $k$-th derivative of such function will be as follows

$$\frac{d^k}{dx^k} (x + a)^n = \begin{cases} \dfrac{n!}{(n - k)!} (x + a)^{n - k}, & \text{if } k \leq n, \\ 0, & \text{if } k > n. \end{cases}$$

This of course can be written using the gamma function, which allows positive non-integer values for $n$ and $k$. It is also my undertsanding that this is consistent with the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative for basic power functions.

$$\frac{d^k}{dx^k} (x + a)^n = \begin{cases} \dfrac{\Gamma(n+1)}{\Gamma(n - k+1)} (x + a)^{n - k}, & \text{if } k \leq n, \\ 0, & \text{if } k > n. \end{cases}$$

This clearly does not work when $n$ is a negative integer, or if $n$ and $k$ are both half integers with $n$ being negative, as then $n-k$ is a negative integer and the gamma function is not defined for those. Here comes my biggest leap of faith in this entire solution. I needed to have a formula which will be consistent with an idea of the fractional derivative, but also will be defined for all negative values of $n$ and $n-k$. I used the recurrent relationship of the gamma function to obtain a different formula. A similar idea has been used in answering this question here and I just expanded the application of this formula with non-integers. Eventually I reached this formula:

$$\frac{\Gamma(q-l)}{\Gamma(-l)} = (-1)^{q} \frac{\Gamma(l+1)}{\Gamma(l-q+1)}$$

Now, this formula is clearly only valid if $q$ is an integer. If $q$ is, let's say. $0.8$, and $l$ is $0.5$, you will have on the LHS the ratio of two real values of the gamma functions, and on the RHS you will have some other ratio of two real values of the gamma function multiplied by ${-1}^{0.8}$ which is complex. However, I decided to use RHS as the basis of defining my fractional derivative, including non-integer values, since even though there is no equality between the two sides when $q$ is non-integer, RHS is always defined for all negative values I need. In fact when I was originally developing the solution of this problem I introduced a different function I called $\Gamma^*$, but right now I see that there is no reason for this. Using two formulas above I said,

let $-l = n-k+1$ and $q-l = n+1$

Therefore $q = k$ and $l = k-n-1$

So for my positive powers my fractional derivative looks like this:

$$D^{k} (x + a)^{n} = \frac{\Gamma(n+1)}{\Gamma(n-k+1)} (x + a)^{n - k}$$

For negative $n$ it switches to this, which is also consistent with Riemann-Liouville definition for negative integer powers. But my intention is to use it for all negative powers (and as you will see, for some positive non integer powers as well).

$$D^{k} (x + a)^{n} = {(-1)}^k\frac{\Gamma(k-n)}{\Gamma(-n)} (x + a)^{n - k}$$

(Note that for the ${(-1)}^k$ term, the principal value is used for non-integer $k$)

As you can see, as long as the order of the derivative is positive and $n$ is negative, resulting inputs for the gamma function will be positive and therefore defined everywhere. Yes, resulting fractional derivatives generally are complex, but I have tested it and if you take, lets say half derivative and then half derivative again you will get first derivative. I will supply a more rigorous proof on request if needed.

Consider this integral

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(x^2 + 1)^{1.5}} \, dx$$

At this point I am going to use the term pseudoresidue to acknowledge the shaky mathematical justification of what I am doing. If we are using the semicircular contour, then there will only be one special point at $x=i$ at which we will evaluate our pseudoresidue.

So I followed the general pattern and said that

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(x^2 + 1)^{1.5}} \, dx = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,i)$$

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, i) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(n)} \lim_{x \to i} \frac{d^{n-1}}{dx^{n-1}} \left[ (x - i)^n f(x) \right]$$

For this case $n=1.5$ hence

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, i) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.5)}\lim_{x \to i} \frac{d^{0.5}}{dx^{0.5}} (x - i)^{1.5} \frac{1}{(x^2 + 1)^{1.5}}$$

This simplifies into

$$\frac{1}{\Gamma(1.5)}\lim_{x \to i}\left( (x+i)^{-1.5} \right)^{(0.5)}$$

So $0.5$-th derivative of a power function of an order $-1.5$. Use the formula from before

$$D^{k} (x + a)^{n} = {(-1)}^k\frac{\Gamma(k-n)}{\Gamma(-n)} (x + a)^{n - k}$$

$k=0.5$, $n=-1.5$ and $a=i$

$$D^{0.5} (x + i)^{-1.5} = {(-1)}^{0.5}\frac{\Gamma(2)}{\Gamma(1.5)} (x + i)^{-2}$$

Hence we get that the total value of pseudoresidue is

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, i)= \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.5)} {(-1)}^{0.5}\frac{\Gamma(2)}{\Gamma(1.5)} (x + i)^{-2}$$

with $x=i$ that yields

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f,i)= \frac{1}{\Gamma\left(1.5\right)} \cdot \frac{i \cdot \Gamma(2)}{\Gamma(1.5)} \cdot (2i)^{-2} = -\frac{i}{\pi}$$

So total integral will be

$$2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,i) = 2$$

Which is correct for this integral.

I tried this with several other values using the same method and it all yielded the correct results. So after that I tried using the general case to obtain a general formula and compare it to what exists in literature and internet. To my surprise this was also successful and I managed to obtain a known general formula.

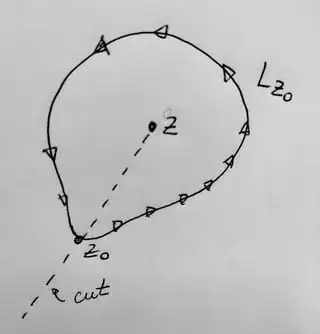

(At this point I realised I have been using $x$ instead of $z$ for complex variable, which is against the convention, so in this example I will be using $z$.)

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(z^2 + a^2)^{m}} \, dz = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,ai)$$

Here $a$ can be any nonzero real number and $m$ is any real number greater that $1/2$.

Using the same semicircular contour around one special point at $z=ai$ we get:

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f,ai) = \frac{1} {\Gamma{(m)}} \lim_{z \to ai} \frac{d^{(m-1)}}{dz^{(m-1)}} \left[ (z - ai)^{m} f(z) \right] = \frac{1}{\Gamma(m)}\lim_{z \to ai}\left( (z+ai)^{-m} \right)^{(m-1)}$$

Using the formula for the fractional derivative of negative power functions we get that

$$D^{k} (z + a)^{n} = {(-1)}^k\frac{\Gamma(k-n)}{\Gamma(-n)} (z + a)^{n - k}$$

For $n=-m$, $k=m-1$ and $a=ai$

$$D^{m-1} (z + ai)^{-m} = {(-1)}^{m-1}\frac{\Gamma(2m-1)}{\Gamma(m)} (z + ai)^{1-2m}$$

Then we return to the pseudoresidue itself with $z=ai$

$$\operatorname{Res}(f,ai) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(m)}(-1)^{m-1} \frac{\Gamma(2m-1)}{\Gamma(m)}(2ai)^{1-2m}$$

Replace $-1 $with $i^2$ Here, as before, we are using principle values for all expressions, so the index laws hold.

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f,ai) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(m)}(i)^{2m-2} \frac{\Gamma(2m-1)}{\Gamma(m)}(i)^{1-2m}(2a)^{1-2m}$$

Let us cancel the powers of $i$

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, ai) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(m)}(i)^{-1} \cdot \frac{\Gamma(2m - 1)}{\Gamma(m)}(2a)^{1 - 2m}$$

Hence we get

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(z^2 + a^2)^{m}} \, dz = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,ai) = {2 \pi}\frac{\Gamma(2m-1)}{\Gamma^2(m)}(2a)^{1-2m}$$

Now, this formula is already correct as far as I tested it for all real $a$ and all real $m>1/2$ but I wanted it to be a bit more rigorous and obtain a formula from another source. So I wanted to get something similar to this. I decided to apply Legendre Duplication formula.

$$\Gamma(z) \cdot \Gamma\left(z + \frac{1}{2}\right) = 2^{1 - 2z} \cdot \sqrt{\pi} \cdot \Gamma(2z)$$

Assume $z=m-1/2$, then

$$\Gamma(2m - 1) = \Gamma(2z) = \frac{\Gamma(z) \cdot \Gamma\left(z + \frac{1}{2}\right)}{2^{1 - 2z} \cdot \sqrt{\pi}} = \frac{\Gamma\left(m - \frac{1}{2}\right) \cdot \Gamma(m)}{2^{2 - 2m} \cdot \sqrt{\pi}}$$

We input the obtained expression for $\Gamma(2m-1)$ into the integral.

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(z^2 + a^2)^{m}} \, dz = 2\pi \cdot \frac{\Gamma\left(m - \frac{1}{2}\right) \cdot \Gamma(m)}{2^{2 - 2m} \cdot \sqrt{\pi} \cdot \Gamma^2(m)} \cdot (2a)^{1 - 2m} = 2\pi\frac{\Gamma\left(m - \frac{1}{2}\right)}{2^{2 - 2m} \cdot \sqrt{\pi} \cdot \Gamma(m)}(2a)^{1 - 2m}$$

Since $(2a)^{1 - 2m} = (2)^{1 - 2m}(a)^{1 - 2m}$

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(z^2 + a^2)^{m}} \, dz = 2\pi \cdot \frac{\Gamma\left(m - \frac{1}{2}\right)}{2^{2 - 2m} \cdot \sqrt{\pi} \cdot \Gamma(m)} \cdot 2^{1 - 2m} \cdot a^{1 - 2m}$$

All the powers of $2$, including the one before $\pi$ will cancel, we will get

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(z^2 + a^2)^{m}} \, dz = \pi \cdot \frac{\Gamma\left(m - \frac{1}{2}\right)}{\sqrt{\pi} \cdot \Gamma(m)} \cdot a^{1 - 2m} = \sqrt{\pi} \cdot \frac{\Gamma\left(m - \frac{1}{2}\right)}{\Gamma(m)} \cdot a^{1 - 2m}$$

Which is almost exactly the formula from the link with the exception of the fact they did not square the term added to $x^2$ and the coefficient for $x^2$ in my case is $1$.

I tried using this method for some more complicated cases and more interesting contours with branch cuts etc. (for example $\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z + 1)^{1.6}} \, dz$) and it also yielded the correct result. As long as there was a nice way do define a fractional derivative of a function using method above (which only works for a small class of functions), my calculations worked.

My question is, why does this work despite the whole idea of non-integer order pole being nonsensical and me choosing rather arbitrary methods to define a fractional derivative for negative power functions? Is this method valid? If so, has it been used before? Can I show it to my students (I am a schoolteacher)?

My apologies for such a long question but I am unable to make it shorter without throwing away key information. I actually had to remove some derivations of some integrals to keep this shorter. I can provide those calculations at request separately if they are needed to clarify anything.

28/05/2025 (around 9 am UK time) UPDATE

This question has gotten some notice and it does not look like I have done something completely silly, so I decided to add another derivation for a completely different type of an integral to illustrate that it works with some other classes of functions as well. I am currently searching for other cases where that easily works, as well as cases where it breaks apart.

Consider $$\int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dz$$

The contour will be made up of four parts: Large circle with $R$ tending to infinity, small circle around origin where $r$ tends to 0 and two branches connecting those circles which are parallel to real axis with $arg(z)=0$ and $arg(z)=2\pi$. It is easy to see that as radii of circles tend to infinity and $0$ respectively the value of those contours will be $0$. So we are left only with two branches.

On the upper path, $arg(z)=0 \Rightarrow z^{1/2} = \sqrt{z}$

On the lower path, $ arg(z)=2\pi \Rightarrow z^{1/2} = \sqrt{z} \cdot e^{2\pi i \cdot \frac{1}{2}} = -\sqrt{z} $

Hence, we get:

$$\int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx + \int_\infty^0\frac{-\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx = 2 \int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx$$

Therefore, considering that there is a special point at $z=-1$, we get

$$2 \int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,-1)$$

Let us evaluate our pseudoresidue.

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, -1) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(n)} \lim_{z \to -1} \frac{d^{n-1}}{dz^{n-1}} \left[ (z + 1)^n f(z) \right]$$

As $n=1.8$ we get:

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, -1) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.8)} \lim_{z \to -1} \frac{d^{0.8}}{dz^{0.8}} \left[ \sqrt{z} \right]$$

Therefore we get $0.8$-th derivative of a function of $0.5$-th power. Let us use the formula I derived at the start:

$$D^{k} (z + a)^{n} = {(-1)}^k\frac{\Gamma(k-n)}{\Gamma(-n)} (z + a)^{n - k}$$

$n=0.8$, $k=0.5$ and $a=0$

Interestingly enough, here the power of the function is positive, so you might think that using formula I derived for negative powers will not yield the correct result, but it will.

$$D^{0.8} (x)^{0.5} = {(-1)}^{0.8}\frac{\Gamma(0.3)}{\Gamma(-0.5)} (z)^{-0.3}$$

Now let us return to the pseudoresidue. Of course $z=-1$

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, -1) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.8)}{(-1)}^{0.8}\frac{\Gamma(0.3)}{\Gamma(-0.5)} (-1)^{-0.3}$$

Let us cancel the powers of $-1$ and simplify.

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, -1) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.8)}\frac{\Gamma(0.3)}{\Gamma(-0.5)}{(i)}$$

Since

$$2 \int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,-1)$$

We get

$$2 \int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx = 2\pi i \cdot \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.8)}\frac{\Gamma(0.3)}{\Gamma(-0.5)}{(i)}$$

Cancel $2$ on both sides and simplify.

$$\int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{z}}{(z+1)^{1.8}} \, dx = -\pi \cdot \frac{1}{\Gamma(1.8)}\frac{\Gamma(0.3)}{\Gamma(-0.5)}$$

I used Wolfram Alpha to evaluate LHS and RHS of this expression, and as far as precision of the computation goes, they are equal.

So here is one extra piece of puzzle for this rather interesting problem I am exploring.

My questions remains the same: Why does it work?

01/06/2025 (around 2:30 am UK time) UPDATE

I keep trying it with more complicated functions.

Consider $$\int_0^\infty \frac{{z}^{1/3}}{(z+1)^{1.9}} \, dz$$

Similarly to the previous example, we will end up with two branches.

On the upper path, $arg(z)=0 \Rightarrow z^{1/3}$

On the lower path, $ arg(z)=2\pi \Rightarrow z^{1/3} = z^{1/3} \cdot e^{2\pi i \cdot \frac{1}{3}} = z^{1/3} \cdot (-\frac{1}{2} + \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}i)$

We flip the sign and bounds of integration for the lower path and get this

$$\int_0^\infty \frac{{z^{1/3}}}{(z+1)^{1.9}} \, dx + (\frac{1}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)\int_0^\infty\frac{{z^{1/3}}}{(z+1)^{1.9}} \, dx = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,-1)$$

To simplify a bit, let us state that $\int_0^\infty \frac{{z^{1/3}}}{(z+1)^{1.9}} \, dx = I$

This will mean that

$$(\frac{3}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)I = 2\pi i \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,-1)$$

Hence

$$I = \frac{2\pi i}{(\frac{3}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)} \cdot \operatorname{PsRes}(f,-1)$$

Let us evaluate pseudoresidue using the same method as before:

$$\operatorname{PsRes}(f, -1) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(n)} \lim_{z \to -1} \frac{d^{n-1}}{dz^{n-1}} \left[ (z + 1)^n f(z) \right]$$

In this case $n=1.9$

Therefore we get $0.9$-th derivative of a function of $\frac{1]{3}$-th power. Using the same formula.

$$D^{k} (z + a)^{n} = {(-1)}^k\frac{\Gamma(k-n)}{\Gamma(-n)} (z + a)^{n - k}$$

We have $n=\frac{1}{3}$, $k=0.9$, $a=0$

$$D^{0.9} (x)^{\frac{1}{3}} = {(-1)}^{0.9}\frac{\Gamma(0.9-\frac{1}{3})}{\Gamma(-\frac{1}{3})} (z)^{\frac{1}{3}-0.9}$$

Again, $z=-1$ so the total pseudoresidue will be

$$D^{0.9} (x)^{\frac{1}{3}} = {(-1)}^{0.9}\frac{\Gamma(0.9-\frac{1}{3})}{\Gamma(-\frac{1}{3})} ({(-1)})^{\frac{1}{3}-0.9}$$

Hence, if we were to evaluate this integral, we get

$$I = \frac{2\pi i}{{(\frac{3}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)} {\Gamma{(1.9)}}}\cdot {(-1)}^{0.9}\frac{\Gamma(0.9-\frac{1}{3})}{\Gamma(-\frac{1}{3})} {(-1)}^{\frac{1}{3}-0.9}$$

Let us cancel powers of $-1$ and simplify $0.9-\frac{1}{3}$ into $\frac{17}{30}$

$$I = \frac{2\pi i}{{(\frac{3}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)} {\Gamma{(1.9)}}}\cdot {(-1)}^{\frac{1}{3}}\frac{\Gamma{(\frac{17}{30})}}{\Gamma(-\frac{1}{3})}$$

Let us evaluate the part of this expression involving $i$

$$\frac{2\pi i}{{(\frac{3}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)}}\cdot {(-1)}^{\frac{1}{3}}$$

We will get a real number, according to Wolfram

Let us evaluate the rest of the expression.

$$\int_0^\infty \frac{{z^{1/3}}}{(z+1)^{1.9}} \, dx = \frac{2\pi i}{{(\frac{3}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} i)} {\Gamma{(1.9)}}}\cdot {(-1)}^{\frac{1}{3}}\frac{\Gamma{(\frac{17}{30})}}{\Gamma(-\frac{1}{3})}$$

Look at LHS and RHS of this expression with Wolfram.

Just like in examples before, they are equal.