Given any set $S$ of $9$ points (no three collinear) within a unit square, there always exist $3$ distinct points in $S$ such that the area of the triangle formed by these $3$ points is less than or equal to $\frac{1}{8}$. Proving existence of a triangle of area $\leq \frac{1}{8}$

That means having 9 points is a sufficient condition for an existing triangle that has area $\leq \frac{1}{8}$. But is it necessary? In other words, if we have less than 9 points, we can always find a placement that all triangle area $> \frac{1}{8}$. Is this true or false?

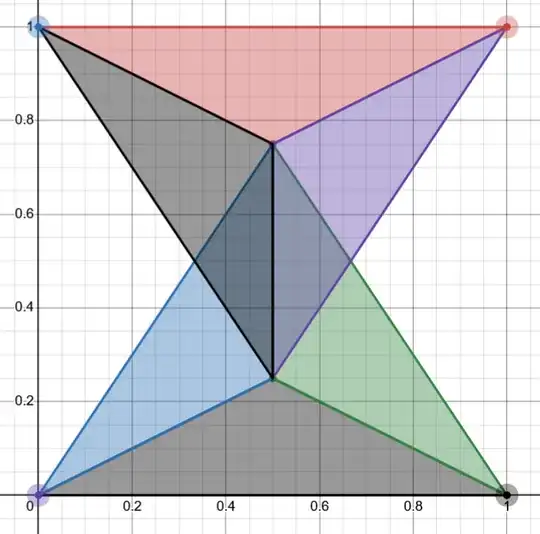

For example, if I place $8$ points in a unit square (no three collinear), is there any placement that the area of the triangle formed by any $3$ points is larger than $\frac{1}{8}$? If such placement exists, how to find it?

I tried to use Python brute-force method (repeated 20000000 times) but failed to find such a placement.

Any idea?