The image of a segment by $z^2$ is a quadratic Bézier curve

The image of a segment by $z^2$ is a quadratic Bézier curve (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B%C3%A9zier_curve) in the plane $\mathbb{C} \simeq \mathbb{R}^2$.

A quadratic Bézier curve is either an arc of a parabola or a straight line segment. Convert quadratic bezier curve to parabola

Let $z_1, z_2 \in \mathbb{C}$ be two distinct points inside the unit disk. The line segment joining them can be parametrized as

$$

z(t) = (1 - t) z_1 + t z_2, \quad t \in [0,1].

$$

Applying the squaring map $z \mapsto z^2$, we obtain the curve

$$

w(t) = z(t)^2 = \left[(1 - t) z_1 + t z_2\right]^2.

$$

Expanding the square:

$$

w(t) = (1 - t)^2 z_1^2 + 2(1 - t)t z_1 z_2 + t^2 z_2^2.

$$

This is exactly the form of a quadratic Bézier curve in the complex plane, with control points:

$$

P_0 = z_1^2, \quad P_1 = z_1 z_2, \quad P_2 = z_2^2.

$$

Therefore, the image of the segment under the map $z \mapsto z^2$ is the curve

$$

w(t) = (1 - t)^2 P_0 + 2(1 - t)t P_1 + t^2 P_2, \ with \ t\in [0,1].

$$

Why is a quadratic Bézier curve a segment of a parabola?

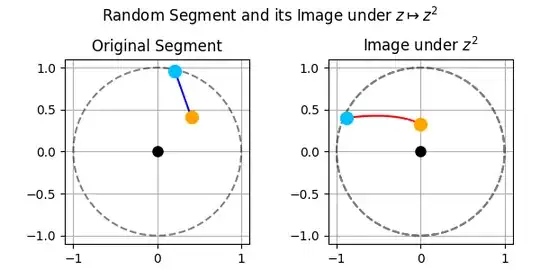

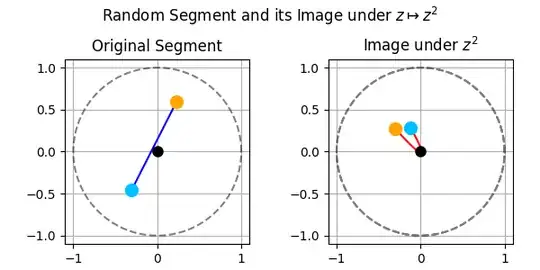

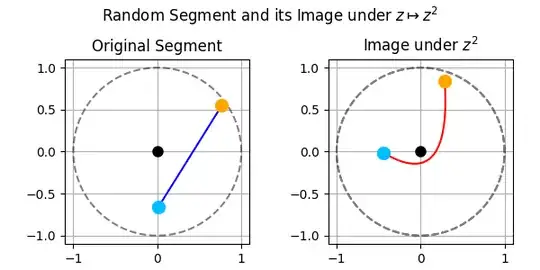

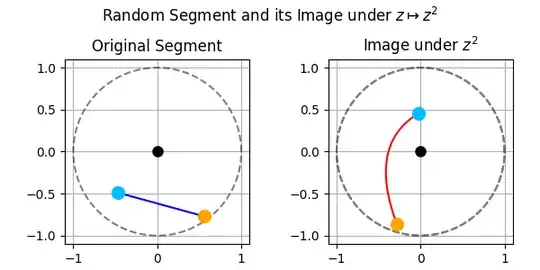

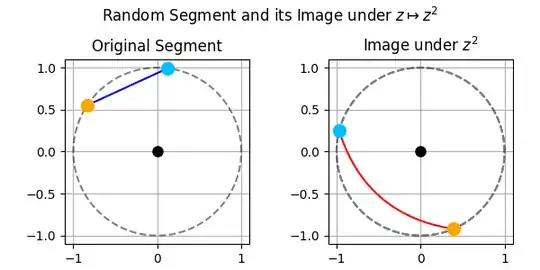

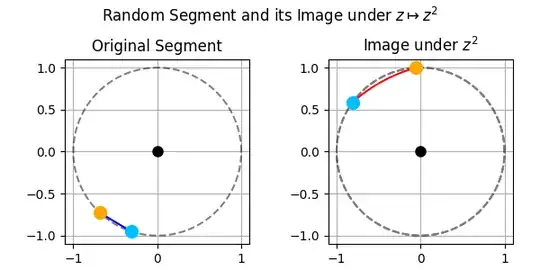

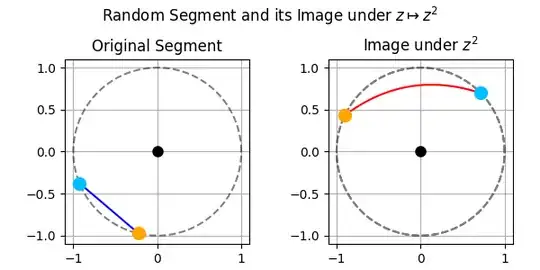

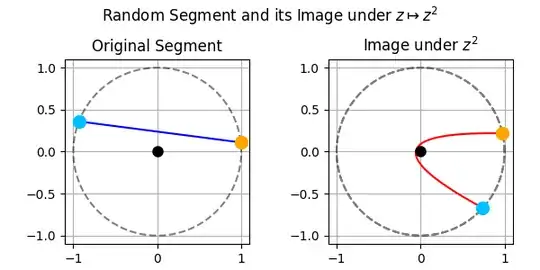

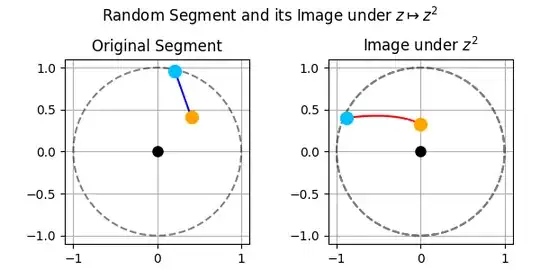

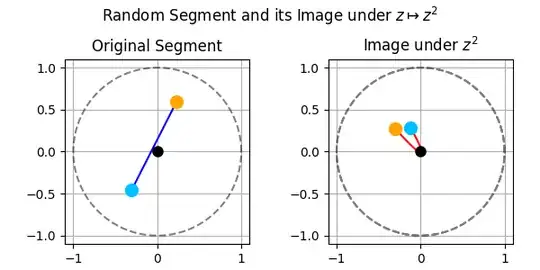

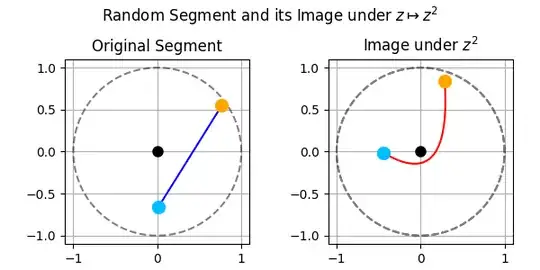

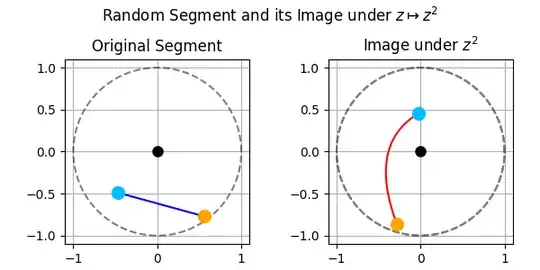

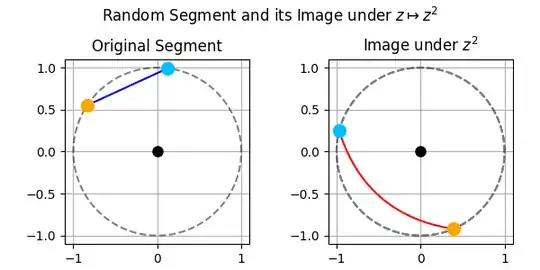

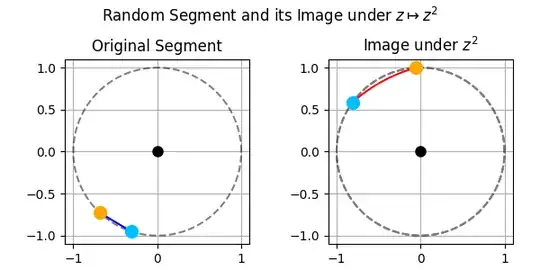

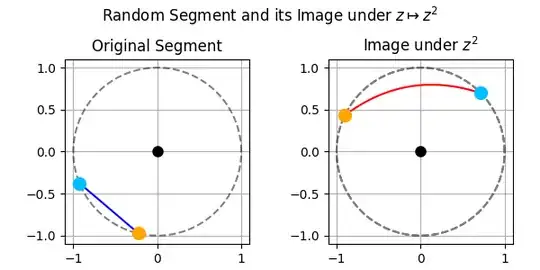

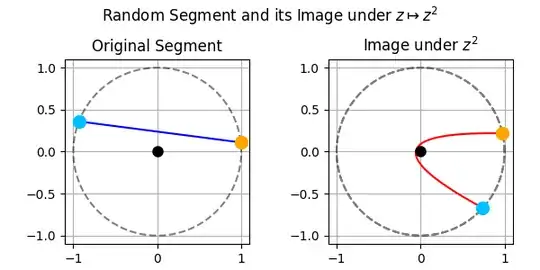

We will consider only the case when $|z_1| = |z_2| = 1$. For the general case, see the reference above. If you visualize a few examples as shown in the images below, you will see that they clearly look like arcs of parabolas.

This is especially evident in the case $|z_1| = |z_2| = 1$, where the Bézier curve has an obvious line of symmetry passing through the origin, aligned with the direction of the midpoint $(z_1^2 + z_2^2)/2$.

Indeed, in this case we have $||P_0|| = |z_1|^2 = 1$ and $||P_2|| = |z_2|^2 = 1$. We assume that $z_1 \neq \pm z_2$ and, to avoid a special case that would require a slightly different approach, we also assume $z_1 \neq \pm i z_2$. We will deal with the case $z_1=\pm i z_2$ later.

Under this assumption, the vectors $z_2^2 - z_1^2$ and $z_2^2 + z_1^2$ are nonzero and orthogonal, since

$$

\langle P_2 + P_0, P_2 - P_0 \rangle = ||P_2||^2 - ||P_0||^2 = 0.

$$

So they form an orthogonal basis of $\mathbb{R}^2$. In particular, there exist real numbers $C$ and $D$ such that

$$

z_1 z_2 = C(z_2^2 + z_1^2) + D(z_2^2 - z_1^2).

$$

But in fact $D = 0$, because

$$

\frac{z_2^2 + z_1^2}{z_1 z_2} = \frac{z_2}{z_1} + \frac{z_1}{z_2} = u + \overline{u} = 2\,\text{Re}(u) \in \mathbb{R},

$$

where $u = z_2/z_1$ satisfies $|u| = 1$, so $z_1/z_2=u^{-1} = \overline{u}$. Because $z_1 \neq \pm z_2$, we have $C \neq \pm \frac{1}{2}$.

Now reparametrize the curve by replacing $t \in [0,1]$ with a new parameter $\alpha \in [-1/2, 1/2]$ defined by $\alpha = t - 1/2$. Then,

$$

w(t) = \left(\frac{1}{4} - \alpha + \alpha^2\right) z_1^2 + 2\left(\frac{1}{4}-\alpha^2 \right) z_1 z_2 + \left(\frac{1}{4} + \alpha + \alpha^2\right) z_2^2, \tag{1}

$$

which simplifies to

$$

w(t) = \alpha (z_2^2 - z_1^2) + \left( \frac{1}{4}(1 + 2C) + \alpha^2(1 - 2C) \right)(z_2^2 + z_1^2).

$$

So, in the basis $(z_2^2 - z_1^2, z_2^2 + z_1^2)$, the image of the line segment is the arc of a parabola parametrized by

$$

\alpha \mapsto \left( \alpha, \frac{1}{4}(1 + 2C) + \alpha^2(1 - 2C) \right), \ with \ \alpha \in [-1/2,1/2].

$$

This is indeed a parabola that does not pass through the origin because $C \neq \pm \frac{1}{2}$.

Note also that we indeed proved that the image of the line segment between $z_1$ and $z_2$ is the entire parabola, since the argument did not rely on the restriction $t \in [0,1]$.

For the case $z_1=\pm i z_2$, that correspond to case of angle $\pi/2$ between $z_1$ and $z_2$, we will have $z_1^2=-z_2^2$ and $z_1z_2=iz_2^2$ and we can consider the simpler orthonormal basis $(z_2^2,iz_2^2)$ instead. From (1) we get, replacing $\alpha\in [-1/2,1/2]$ by $\beta=2\alpha\in [-1,1]$,

$$w(t)=\beta z_2^2 + \left(\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\beta^2\right)iz_2^2,$$

So in this orthonormal coordinate system, the parabola is given by

$$\beta \mapsto \left(\beta, \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{2} \beta^2\right),

$$

which is convenient because we can directly apply the standard formula for the focus of a parabola of the form $y = a + b x^2$ in this case.

$$F=\left(0,a+\frac{1}{4b}\right)=\left(0,0 \right).$$

The focus of the parabola is the origin.

So the focus in the case $z_1 = \pm i z_2$ is the origin. Since the examples below and Eric in the comments suggest that this is always the case, we will now prove it. When $z_1 \neq \pm i z_2$, the basis $(z_2^2 - z_1^2, z_2^2 + z_1^2)$ may not be orthonormal, so we cannot use the classical formula for the focus unless we perform boring and lengthy calculations to normalize the basis. Instead, I will use a different approach.

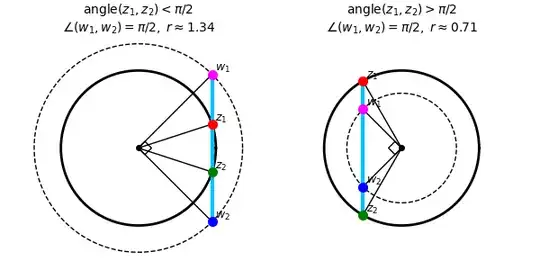

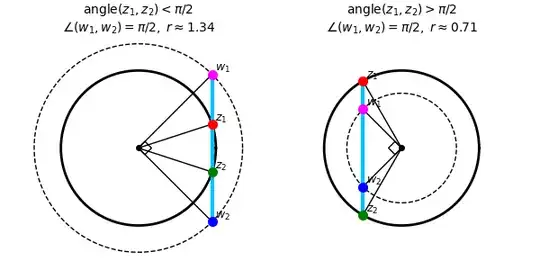

If the angle between $z_1$ and $z_2$ is smaller than $\pi/2$, it is easy to see that one can find a radius $r > 1$ such that the line between $z_1$ and $z_2$ intersects the circle $|z| = r$ at two points $w_1$ and $w_2$ such that the angle between them is $\pi/2$.

Analogously, if the angle between $z_1$ and $z_2$ is larger than $\pi/2$, we can find a radius $r < 1$ such that the line between $z_1$ and $z_2$ intersects the circle $|z| = r$ at two points $w_1$ and $w_2$ such that the angle between them is again $\pi/2$.

Since the line between $z_1$ and $z_2$ has the same image under $z \mapsto z^2$ as the line between $w_1$ and $w_2$, its image under $z^2$ is the same parabola.

Now, the points $w_1/r$ and $w_2/r$ are in the unit circle and they have an angle of $\pi/2$ between them. We already proved that the image of the segment $[w_1/r, w_2/r]$ is an arc of a parabola with focus at the origin. This implies that the image of $[w_1, w_2]$ under $z^2$ is also a parabola with focus at the origin. I am using two facts here: for $r \neq 0$ and $S \subset \mathbb{C}$, define $rS = \{rs \colon s \in S\}$. Then:

A. For every $r \neq 0$, the transformation $z \mapsto rz$ takes a parabola $P$ with focus $F$ to a parabola $rP$ with focus at $rF$. This follows from the geometric definition of a parabola.

B. Let $\phi(z) = z^2$. If $S$ is a subset of $\mathbb{C}$, then $\phi(rS) = r^2 \phi(S)$. This is a simple calculation.

Examples

Examples if the extremes lie in the unit circle $|z_1|=|z_2|=1$

Examples if the extremes do not lie on the unit circle