Are all ODE solutions analytic and representable by Taylor series?

I'm exploring how Taylor expansions relate to the solutions of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Starting from the basic definition of the derivative, I constructed the following reasoning:

Let

$$ f'(a) = \lim_{\epsilon \to 0} \frac{f(a + \epsilon) - f(a)}{\epsilon} $$

This gives the first-order approximation:

$$ f(a + \epsilon) = f(a) + \epsilon f'(a) \tag{1} $$

Define a discrete sequence of points:

$$ f[n] = f(a + n\epsilon) $$

So:

$$ f[0] = f(a), \quad f[1] = f(a + \epsilon), \quad f[2] = f(a + 2\epsilon), \ldots $$

We can expand this step-by-step:

First-order step: $$ f[1] = f[0] + \epsilon f'[0] \tag{2} $$

Next step: $$ f[2] = f[1] + \epsilon f'[1] = f[0] + \epsilon f'[0] + \epsilon f'[1] \tag{3} $$

Using: $$ f'[1] = f'[0] + \epsilon f''[0] \tag{4} $$

Substitute (4) into (3): $$ f[2] = f[0] + 2\epsilon f'[0] + \epsilon^2 f''[0] \tag{5} $$

Continuing this pattern, we obtain: $$ f[n] = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \binom{n}{k} \epsilon^k f^{(k)}(a) $$

By letting $ x = a + n\epsilon$, this resembles the Taylor series: $$ f(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(x - a)^k}{k!} f^{(k)}(a) $$

So this derivation intuitively shows that derivatives encode local information, and Taylor series propagate this locally to estimate global behavior. This makes me think:

- As long as the function is infinitely differentiable, Taylor expansion should represent the ODE solution.

However, we know not all smooth functions are analytic. A famous counterexample is:

$$ f(x) = \begin{cases} e^{-\frac{1}{x}} & \text{if } x > 0, \\ 0 & \text{if } x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

This function is smooth everywhere, but its Taylor series at ( x = 0 ) is identically zero and does not match the function for ( x > 0 ).

But from a dynamical systems perspective, such a function seems unphysical: if all derivatives at a point (position, velocity, acceleration, etc.) are zero, then the object shouldn't move. Yet this function “spontaneously” becomes non-zero.

So here’s my question:

Can we conclude that any solution to a physical ODE (such as from a dynamical system) must be analytic?

Or are there meaningful physical systems that admit non-analytic (but smooth) solutions?

This is full version of my proof

Now extend this to the next point:

$$ f[3] = f[2] + \epsilon f'[2] \tag{6} $$

Using the same logic recursively:

$$ f'[2] = f'[1] + \epsilon f''[1] = f'[0] + \epsilon f''[0] + \epsilon(f''[0] + \epsilon f^{(3)}[0]) = f'[0] + 2\epsilon f''[0] + \epsilon^2 f^{(3)}[0] \tag{7} $$

Substitute this into (6):

$$ f[3] = f[2] + \epsilon \left( f'[0] + 2\epsilon f''[0] + \epsilon^2 f^{(3)}[0] \right) \tag{8} $$

Now, using equation (5) for ( f[2] ), we get:

$$ f[3] = f[0] + 2\epsilon f'[0] + \epsilon^2 f''[0] + \epsilon f'[0] + 2\epsilon^2 f''[0] + \epsilon^3 f^{(3)}[0] $$

Combine terms:

$$ f[3] = f[0] + 3\epsilon f'[0] + 3\epsilon^2 f''[0] + \epsilon^3 f^{(3)}[0] \tag{9} $$

Now, I notice that the coefficients of each term form Pascal’s triangle, so we can express it as:

$$ f[n] = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \binom{n}{k} \epsilon^k f^{(k)}(a) $$

Or equivalently:

$$ f[n] = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{n!}{k!(n - k)!} \, \epsilon^k \, f^{(k)}(a) $$

Now, if we want to find $ f(a+x) $, we can set $N = \frac{x}{\epsilon}$, but as $\epsilon $ approaches $0$, $ N$ approaches infinity, so:

$$ f(a+x) = \lim_{N \to \infty} f[N] $$

Now we get:

$$ f(a+x) = \lim_{N \to \infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{N!}{k!(N - k)!} \, \epsilon^k \, f^{(k)}(a) $$

As $ N \gg k $, we approximate $ \frac{N!}{(N - k)!} \approx N^k $, so:

$$ f(a+x) = \lim_{N \to \infty} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(N\epsilon)^k}{k!} \, f^{(k)}(a) $$

Since $N = \frac{x}{\epsilon} $, we have $ N\epsilon = x $, so:

$$ f(a+x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^k}{k!} \, f^{(k)}(a) $$

Update

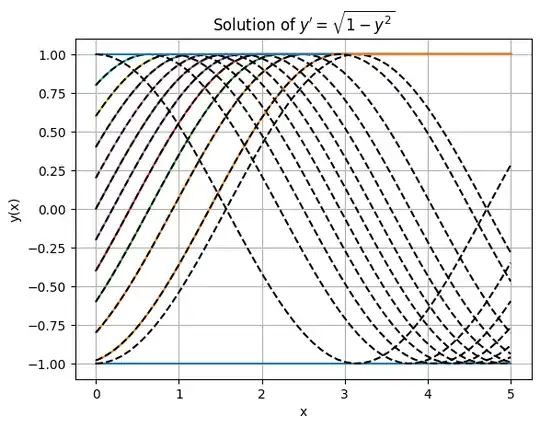

I've consider the $y' = sqrt(1 - y^2)$, here the result I've got from rk45

However, if we do Taylor expansion within the interval [-1,1], the derivative of $y'(x) $respect to the order is alternating, matching Taylor expansion of sine function.

From the plot, I saw the trajectory follow sine function until it reach $y = 1$ and the one that initialized at $y=-1$ stay the same at $-1$.

For me, I consider the numerical result as intuitive one, but Taylay expansion predict otherwise. So from this counter example it clearly show that Taylor expansion can approximate ode solution atleast in locally. It is not alway analytic and some of them is not representable by Taylor series.