Context: I am currently reading Watson's 1961 paper "Goodness-Of-Fit Tests on a Circle". At a certain step, He produces the following relation (Equation (18) to (20) if you are able to read the actual paper):

$$\frac{\sqrt{\theta/2}}{\sin(\sqrt{\theta/2})}=2\sum_{m=1}^{+\infty}\frac{(-1)^{m-1}}{1-\frac{\theta}{2m^2\pi^2}}$$

(by expanding Euler's infinite product formula for $\sin$).

Question: the general term of the above series representation doesn't converge to $0$. What sense can we give to this sum ?

Additional context: He then apply the inverse Laplace transform term by term, so the notion of convergence should be "strong enough" to allow some kind of linearity.

What I think, so far:

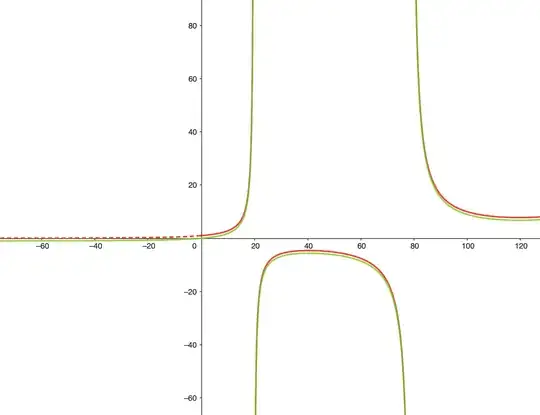

- I displayed the graph of both functions :

The red graph is the left hand side of the equality, extended for negatives values of $\theta$ by

$$\frac{\sqrt{-\theta/2}}{\sinh(\sqrt{-\theta/2})}$$

(dashed line), and the green graph is the right hand side, truncated at the first twenty terms (even pushing a bit more doesn't give a perfect fit).

The red graph is the left hand side of the equality, extended for negatives values of $\theta$ by

$$\frac{\sqrt{-\theta/2}}{\sinh(\sqrt{-\theta/2})}$$

(dashed line), and the green graph is the right hand side, truncated at the first twenty terms (even pushing a bit more doesn't give a perfect fit). - I know Watson is well known for computing asymptotic series expansion (in the sense introduced by Poincaré) of Laplace transforms, could it be such expansion (for small $\theta$)?

- Is he using some alternative notion of convergence (Borel summation for example, which is often used in the context of Laplace transforms)?