I. Data

Ramanujan found,

$$\pi\approx \frac{9}{5}+ \sqrt{ \frac{9}{5} } = 3.1416\dots $$

As John Alexiou stated in this 2012 post, the golden ratio $\phi$ is exactly,

$$ \phi = \frac{5}{6} \left( \frac{9}{5}+\sqrt{\frac{9}{5}}\right) - 1 $$

and Jaume Oliver Lafont pointed out in his answer that this is equivalent to,

$$ \phi^2 = \frac{5}{6} \left( \frac{9}{5}+\sqrt{\frac{9}{5}}\right)\qquad$$

since $\phi^2=\phi+1$. Of course, this immediately implies,

$$ \frac{6\,\phi^2}{5} \approx \pi\qquad$$

Interestingly, the approximation seems long known by the French from the 12th century. (See Frédéric Beatrix's "Squaring the circle like a medieval master mason", Section 5, Proposed dating for the approximation $\frac{6\,\phi^2}{5} \approx \pi$.)

II. Squaring the circle

From this answer by Tankut Begyu on a post about geometric constructions, taking the square root of both sides, we get,

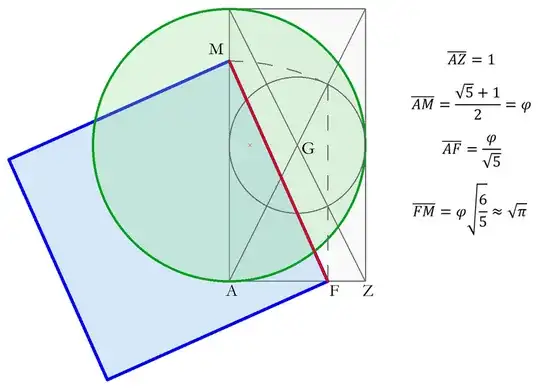

$$\overline{FM}= \phi\sqrt{\frac65}\approx\sqrt{\pi}$$

and this is the red line segment in Beatrix's construction below,

III. Pi formulas

In Ramanujan's 1914 paper, "Modular Equations and Approximations to $\pi$", one formula is,

$$\frac1{\pi}=\frac{-1+5\sqrt5}{2^5}+\frac1{2^5}\sum_{n=1}^\infty\frac{(2n)!^3}{n!^6} \frac{(30n-1)+(42n+5)\sqrt5}{(2^{12}\phi^8)^n}$$

If we truncate this, then,

$$\frac1{\pi}\approx\frac{-1+5\sqrt5}{2^5}$$

but is not Ramanujan's other approximation,

$$\pi\approx \frac{9}{5}+ \sqrt{ \frac{9}{5} }$$

even if we flip it over.

IV. Question

Is there an unknown Ramanujan-type pi formula such that if we trucate it, then,

$$\frac1{\pi}\approx \left(\frac{9}{5}+ \sqrt{ \frac{9}{5} }\right)^{-1}$$

is the first approximation?

Edit: In response to a comment, a Ramanujan-type pi formula has the simple form,

$$\frac1{\pi}=\sum_{n=0}^\infty S(n) \frac{An+B}{C^n}$$

where $(A,B,C)$ are algebraic numbers and $S(n)$ is one of four well-defined integer sequences. Given the Pochhammer symbol $(a)_n$ or binomial coefficients $\binom{n}{k}$, these are,

\begin{align} S_1(n) &= \frac{(1/2)_n(1/6)_n(5/6)_n\, 1728^n }{n!^3} = \binom{2n}{n}\binom{3n}{n}\binom{6n}{3n}= \frac{(6n)!}{(3n)!\,n!^3}\\ S_2(n) &= \frac{(1/2)_n(1/4)_n(3/4)_n\, 256^n}{n!^3} \, = \, \binom{2n}{n}\binom{2n}{n}\binom{4n}{2n} = \frac{(4n)!}{n!^4}\\ S_3(n) &= \frac{(1/2)_n(1/3)_n(2/3)_n\, 108^n}{n!^3} \, = \, \binom{2n}{n}\binom{2n}{n}\binom{3n}{n} = \frac{(2n)!\,(3n)!}{n!^5}\\ S_4(n) &= \frac{(1/2)_n(1/2)_n(1/2)_n\, 64^n}{n!^3} \; = \; \binom{2n}{n}\binom{2n}{n}\binom{2n}{n} \; = \;\frac{(2n)!^3}{n!^6} \end{align}

or explicitly,

$S_1(n) = 1, 120, 83160, 81681600,\dots$ (A001421)

$S_2(n) = 1, 24, 2520, 369600,\dots$ (A008977)

$S_3(n) = 1, 12, 540, 33600,\dots$ (A184423)

$S_4(n) = 1, 8, 216, 8000,\dots$ (A002897)

P.S. Ramanujan gave 17 such formulas in his 1914 paper, but there are actually 36 formulas where $(A,B,C)^2$ are integers (he missed half, mostly from $S_1$), and infinitely many if they are algebraic numbers. A Ramanujan-Sato formula for $\dfrac1{\pi}$ of level 5 and above uses different $S(n)$ and $C$ is a value of a modular form.