We can just take the sum of the geometric series. This gives

$$P(x) = \frac{x^{k+1} - 1}{x - 1} + (c - 1)$$

so the roots of $P(x)$ are the roots $\neq 1$ of the much sparser polynomial

$$(x - 1) P(x) = x^{k+1} - 1 + (c-1)(x-1) = x^{k+1} + (c-1)x - c.$$

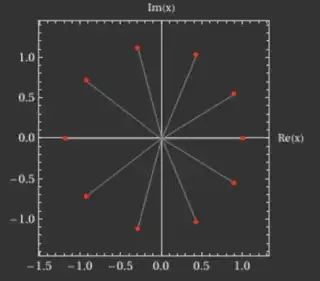

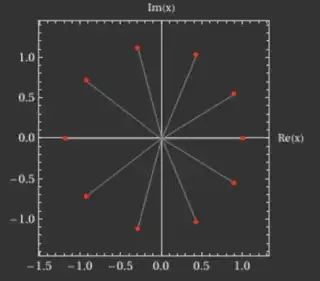

For large $k$ and small $c$ this shows that $|x|$ has to be fairly small, say at most $1 + O \left( \frac{1}{k} \right)$, and the roots should be spread out roughly like the $k$-th roots of unity, and this can be verified experimentally with e.g. WolframAlpha. Here are the roots for $k = 9, c = 3$, so $x^{10} + 2x - 3$:

This actually turns out to be generic behavior for polynomials of high degree with small coefficients; asymptotically their roots become uniformly distributed on the unit circle. See the very nice discussion at Why do roots of polynomials tend to have absolute value close to 1? for more.

More refined information about the roots can be found depending on what you want to do (I assume estimating the largest or smallest root). You can see examples of this kind of analysis in Flajolet and Sedgewick's Analytic Combinatorics in the discussion of asymptotics for rational generating functions in Chapter V.

Specifically, Example V.4 discusses the special case $c = -1$ in detail, which occurs when studying longest runs of heads in coin flips (if this is similar to or the same as your problem, see this math.SE thread and The Longest Run of Heads by Schilling for more, in addition to F-S). Here we want to estimate the smallest positive real root. We can rewrite $x^{k+1} = 2x - 1$ as

$$x = \frac{1 + x^{k+1}}{2}$$

and use this as a fixed point recursion to get that the smallest positive real root is about $\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2^{k+2}}$.