Notations are in mathematics a matter of choice. They should help and should be chosen so that they fit to the usual human way of always putting letters on the central objects, and be as close as possible to existing formulas that we have applied or will apply hundred times. If a problem starts with "Let $\Delta\; \Theta\epsilon \mathcal G$ be a triangle with centroid $I$..." then everybody will quit that book, and in an exam will use better letters for the vertices and the centroid. I would use a triangle $\Delta ABC$ and denote the centroid by $G$ as everybody does.

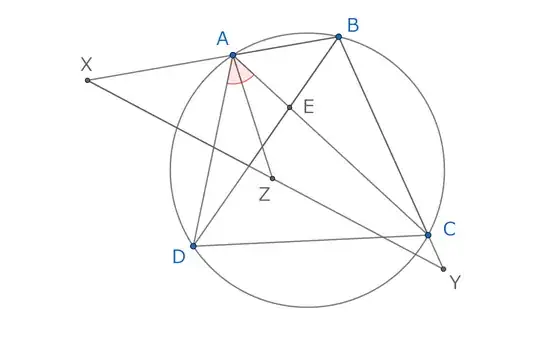

A similar situation is in the present question. Somebody wants to hide a simple property behind a scrambled notation that does not suggest how simple the story may be. My first reaction was of course to use the letters i need at the places i need. Here is a translation into human of the given story:

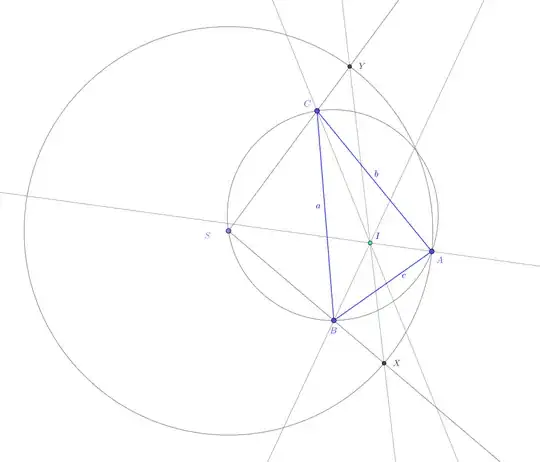

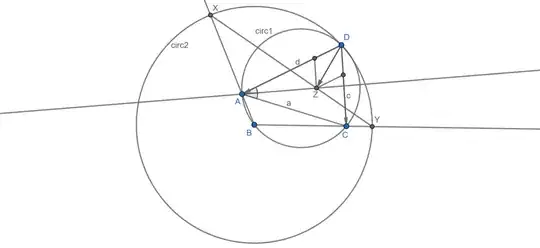

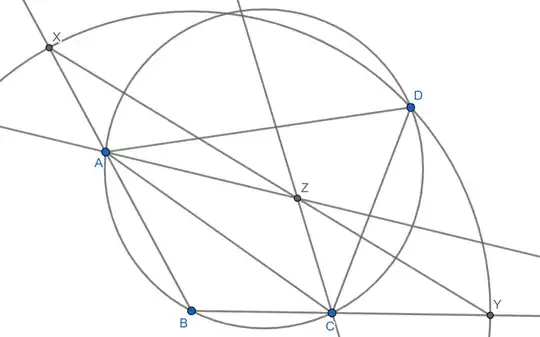

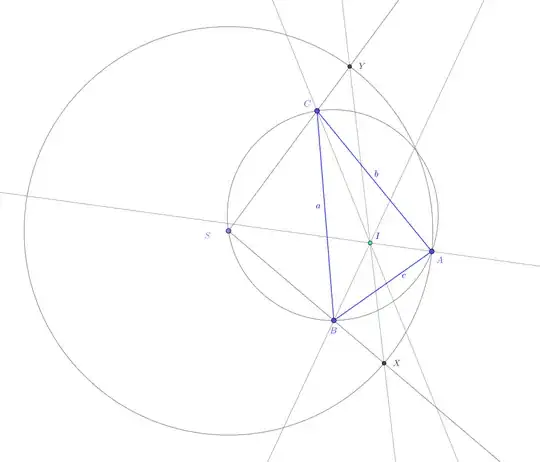

Let $\Delta ABC$ with sides denoted as usual by $a,b,c$ (the lower case letter

side corresponds to the side opposite to the vertex denoted by the same upper case letter). Let $I$ be the incenter of $\Delta ABC$.

On the circumcircle of the triangle let $S$ be a point on the arc $\overset{\Large\frown}{BC}$ (not containing $A$). The circle centered in $S$ with radius $SA$ intersects the rays $SB,SC$ in the points $X,Y$ respectively.

Then the points $X,Y,I$ are collinear.

Note: The claimed relations follows now from the known formula for the barycentric coordinates of the incenter (computed w.r.t. $\Delta ABC$ in terms of its side lenghts $a,b,c$):

$$

I=[a:b:c]=\frac 1{a+b+c}(a,b,c)\ ,

$$

where the first notation $[a:b:c]$ uses unnormed barycentric coordinates, the second one being the normed version in vectorial notation.

Then we have formally (e.g. by identifying points with their position

in the cartesian plane, i.e. using their affixes):

$$

I = \frac 1{a+b+c}(aA+bB+cC)\ .

$$

Equivalently, for one or for each point $X$ in the plane we have vectorially:

$$

\overrightarrow{XI} = \frac 1{a+b+c}\left(

a\overrightarrow{XA} +

b\overrightarrow{XB} +

c\overrightarrow{XC}\right)\ .

$$

(Apply this for $X=A$, while at least a posteriori we have $Z=I$, where $Z$ is defined as in the question as $CI\cap XY$.)

I will give a proof that is maybe best suited in the context, we use barycentric coordinates. For a short overview:

Barycentric Coordinates for the Impatient,

Max Schindler and Evan Chen

Let $S=(s,t,u)$ be the barycentric coordinates of $S$.

Since $S\in \overset{\Large\frown}{BC}$, the points $A,S$ are in opposite half-planes w.r.t. the line $BC$. This shows that the signs of $s,t,u$ are $-++$, we will need this below.

A general point will have coordinates $(x,y,z)$. The equation of the circumcircle is (Corollary 9) $0=a^2yz+b^2zx+c^2xy$. So $(s,t,u)$ satisfies this equation, i.e.

$$

0=a^2tu+b^2us+c^2st\ .

$$

We list and compute now some points and some lengths of segments:

$$

\begin{aligned}

A &= (1,0,0)\ ,\\

B &= (0,1,0)\ ,\\

C &= (0,0,1)\ ,\\

I &= [a:b:c]\ ,\\

S &= (s,t,u)\text{ with }1=s+t+u\ ,\ 0=a^2tu+b^2us+c^2st\ ,\\

\overrightarrow {AS} &=(s-1,t-0,u-0)=(s-1,t,u)\ ,\\

SA^2 &=-a^2tu-b^2u(s-1)-c^2(s-1)t=b^2u+c^2t\ ,\\[2mm]

s^2\; SA^2 &=s(b^2us+c^2st)=-a^2\; stu\\

&=a^2\Pi^2\qquad\qquad\text{ with }\Pi^2:=-stu\ ,\ \Pi>0\ ,\\

t^2\; SB^2 &=b^2\Pi^2\ ,\\

u^2\; SC^2 &=c^2\Pi^2\ ,\\[3mm]

SA &=-\frac as\Pi\ ,\qquad (s<0)\\

SB &=+\frac bt\Pi\ ,\qquad (t>0)\\

SC &=+\frac cu\Pi\ ,\qquad (u>0)\\[3mm]

X &=S+\frac {SA}{SB}(B-S)=(s,t,u)-\frac {at}{bs}(-s,1-t,-u)

\\

&=\frac 1{bs}\Big(\ s(at+bs)\ ,\ t(at+bs)-at\ ,\ u(at+bs)\ \Big)

\\

&=\Big[\ s(at+bs)\ :\ t(at+bs)-at\ :\ u(at+bs)\ \Big]\ ,\\[2mm]

Y &=S+\frac {SA}{SC}(C-S)=(s,t,u)-\frac {au}{cs}(-s,-t,1-u)

\\

&=\frac 1{cs}\Big(\ s(au+cs)\ ,\ t(au+cs)\ ,\ u(au+cs)-au\ \Big)

\\

&=\Big[\ s(au+cs)\ :\ t(au+cs)\ :\ u(au+cs)-au\ \Big]\ .

\end{aligned}

$$

The needed collinearity is equivalent to the vanishing of the determinant

obtained by using (possibly unnormed) coordinates for the points $I,X,Y$.

When computing this determinant we omit possible non-zero factors,

in this case instead of equality we write $\sim$ to have a short notation,

and also not collect factors that in the end do not matter.

$$

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{vmatrix}

a & b & c\\

s(at+bs) & t(at+bs)-at & u(at+bs)\\

s(au+cs) & t(au+cs) & u(au+cs)-au

\end{vmatrix}

\sim

\begin{vmatrix}

\frac as\color{gray}{stu} & \frac bt\color{gray}{stu} & \frac cu\color{gray}{stu}\\

1 & 1-\frac{a}{at+bs} & 1\\

1 & 1 & 1-\frac {a}{au+cs}\\

\end{vmatrix}

\\

&\qquad\sim

\begin{vmatrix}

atu & bsu-atu & cst-atu\\

1 & -\frac{a}{at+bs} & 0\\

1 & 0 & -\frac {a}{au+cs}\\

\end{vmatrix}\sim

\begin{vmatrix}

atu & bsu-atu & cst-atu\\

at+bs & -a & 0\\

au+cs & 0 & -a\\

\end{vmatrix}

\\

&\qquad

\sim a^3tu +au(bs-at)(bs+at)+at(cs-au)(cs+au)

\\

&\qquad

\sim a^2tu +u(b^2s^2-a^2t^2) +t(c^2s^2-a^2u^2)

\\

&\qquad

= a^2\; tu(1-t-u) + b^2\; s^2u+ c^2\;s^2t

\\

&\qquad

= s(a^2\; tu + b^2\; us+ c^2\;st)=0\ .

\end{aligned}

$$

The points $X,Y,I$ are thus collinear.

$\square$