Consider the closed unit ball in $\mathbb{R}^n$:

$$B_n: = \left\{ x \in \mathbb{R}^n \mid \|x\|_2 \le 1 \right\}.$$

Also define:

$$S_{n,m}(a_1,\dots,a_m,b_1,\dots,b_m) := \left\{x\in\mathbb{R}^n \mid \forall i\in\{1,\dots,m\},a_i\|x\|_1+b_i\|x\|_\infty\le 1 \right\}.$$

I want to choose $m, a_1,\dots,a_m,b_1,\dots,b_m\ge 0$ to minimize the volume of the set $S_{n,m}(a_1,\dots,a_m,b_1,\dots,b_m) \setminus B_n$ subject to $B_n\subseteq S_{n,m}(a_1,\dots,a_m,b_1,\dots,b_m)$.

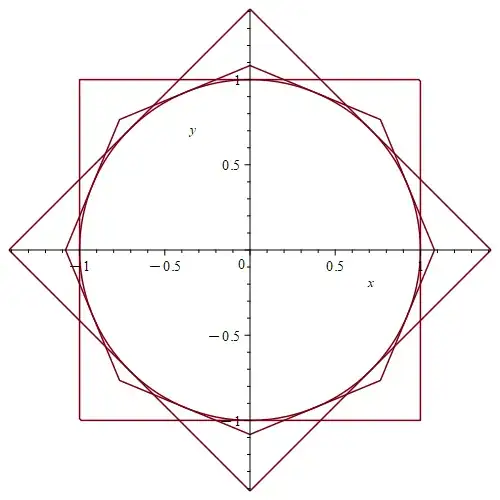

I presume the list should start with $a_1=0,b_1=1$ and $a_2=\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}},b_2=0$ (see e.g. Equivalence of norms in $\mathbb{R^n}$), but how many more items should be in the parameter list? Certainly at least one, as shown by the following plot for $n=2$:

Generated with the following MAPLE code:

plots[implicitplot]([abs(x)+abs(y)+sqrt(2)*max(abs(x),abs(y))=2*(1 + sqrt(2))/sqrt(2 + sqrt(2)),max(abs(x),abs(y))=1 , abs(x)+abs(y)=sqrt(2),x^2+y^2=1],x=-sqrt(2)..sqrt(2),y=-sqrt(2)..sqrt(2));

Here,

$$a_3=\frac{\sqrt{2 + \sqrt{2}}}{2 + 2\sqrt{2}}, \qquad b_3=\sqrt{2}\frac{\sqrt{2 + \sqrt{2}}}{2 + 2\sqrt{2}}$$

I produced these numbers by first noting that the set

$$\left\{ x \in \mathbb{R}^2 \mid \|x\|_1+\sqrt{2}\|x\|_\infty= 1+\sqrt{2} \right\}$$

touched the unit circle in eight places from the inside, then scaling this shape up so that it was bigger than the unit circle. Is this optimal in two dimensions? Does it generalize?

Update: Having thought some more, I now see that $m=\infty$ is optimal. For any $b\le 1$, you can choose $a$ to ensure tangency to the circle. The tangency point is continuous in $b$, and so it traces out the entire circle as $b\rightarrow 0$.

Is there anything special about $m=3$? It certainly seems natural, given that the vertexes are on the same rays for any parameters.