I am trying to understand intuitively how the spectrum $\mathbb{S}$ of the stable homotopy groups of spheres arises from the diagrammatic approach hinted at e.g. in John Baez's TWF 102, by explicitly finding the first few stable homotopy groups $\pi_0, \pi_1, \ldots$ Ideally I would want to work out everything up to the third stable homotopy group $\pi_3$ and see where the $24$ comes from, but I'm having trouble already at the second stable homotopy group.(*)

The idea described in the previous link is to start with the natural numbers, thought of as cardinalities of finite sets, and then categorify, i.e. think of equalities as paths, or motions, transforming a set to itself. These paths are then treated as objects in their own right, one dimension higher. Since there is a notion of when two paths are "close" to each other, the paths have their own equivalences, which then generate new objects one dimension higher, and so on.

When one does this and adds negative elements to get the integers $\mathbb{Z}$, plus the paths corresponding to the ways of cancelling them, plus the surfaces corresponding to the ways of cancelling the new paths, etc., the resulting structure is equivalent to the sphere spectrum $\mathbb{S}$, with the group structure given by disjoint union (I believe the ring structure can also be defined by some variation of Cartesian product). As Baez mentions, this has led some people to consider $\mathbb{S}$ as the "true integers" in some sense, see e.g. this MathOverflow question. On the other hand, this gives an alternate way to visualize elements of $\pi_n \in \mathbb{S}$ geometrically in terms of $n$-dimensional hypersurfaces in $n+1$ dimensions.

The groups $\pi_0$ and $\pi_1$

I believe I have a good grasp of how the zeroth and first stable homotopy groups of $\mathbb{S}$ arise. To start with, a natural number $n$ is represented as a set of $n$ points arranged in a straight line. The symmetries of this set consist of all the ways of permuting the points, and the corresponding motions are represented as sets of one-dimensional lines in the plane, connecting each starting point to its final position. To keep track of the direction of motion, the lines are assigned an orientation from top to bottom. This is called a string diagram or line diagram.

Lines are allowed to cross each other ($\dagger$), with no distinction between over-crossings and under-crossings; roughly speaking two line diagrams are regarded as equivalent (for which I'll use the notation $=_\text{1D}$) if one can smoothly deform the first diagram to the other without creating any cusp singularities in the process, i.e. using the second and third Reidemeister moves to move the crossings around (an intuitive reasoning for not allowing the first Reidemeister move is that at some point during the deformation, a cusp is created where the tangent vector of a single line is not well-defined, thus the diagram can't be properly interpreted as representing a smooth motion of points with constant speed. The appropriate mathematical concept defining a valid string diagram is that of an immersion of oriented intervals into $\mathbb{R}^2$).

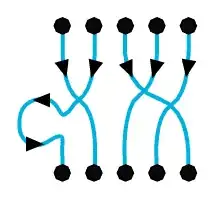

This is a complicated structure, since for each number $n$ there are $n!$ different permutations and thus $n!$ possible string diagrams up to deformation, but much of that structure collapses when one adds negative points. A set with $n$ regular (positive) points and $m$ negative points represents the integer $n-m$. Since $n-m = (n+1)-(m+1)$, there are new allowed lines corresponding to creating or cancelling a pair of opossitely-signed points.

In order to be able to assign a consistent orientation to the new creation/annihilation lines, the lines coming out of negative points are forced to have the opposite orientation, as if the points were moving backwards in time; a similar convention is used in particle physics to draw Feynman diagrams containing antiparticles.

Since a state with two opossitely-signed points very close to each other should be considered "similar" to a state with no points at all, the allowed deformations of the paths include two new ones:

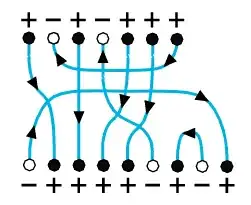

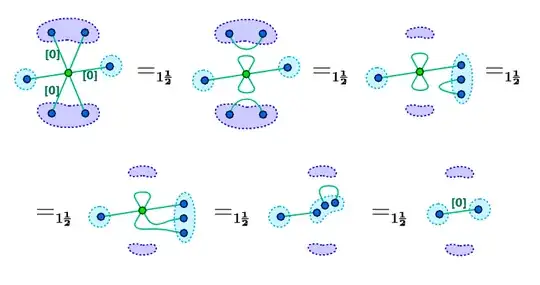

These two deformations allow for the isolation of a simple crossing, as follows:

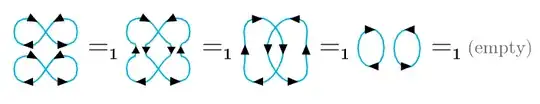

This isolated simple crossing in fact corresponds to the complex Hopf fibration $\eta \in \pi_1$ generating the first stable homotopy group of the sphere spectrum. So all sets of lines from $n$ to $n$ can be deformed in this way into the disjoint union of $n$ straight vertical lines plus a bunch of isolated simple crossings. Two of these isolated simple crossings cancel as follows:

corresponding to the equation $2\eta=0$ in $\mathbb{S}$.

Thus there exists an algorithm that reduces any valid configuration of lines in the plane to a canonical representative in $\pi_0 \oplus \pi_1 \simeq \mathbb{Z} \oplus \mathbb{Z}_2 \eta$:

Deform the lines if necessary so that there are only simple crossings.

Isolate all crossings as above.

Cancel the crossings in pairs until we are left with at most one.

- Cancel pairs of positive/negative points and their associated lines.

The resulting element is the resulting number $n$ of lines with their associated points (so $n$ can be positive, zero or negative) if there is no isolated crossing at the end of the process, or $n+\eta$ if there is one. The presence or absence of $\eta$ is related to the concept of parity of a permutation.

The group $\pi_2$

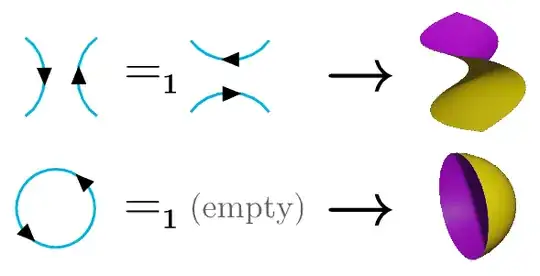

The second stable homotopy group would be obtained by "categorifying" again, taking all valid 1D-deformations of the lines and promoting them to the surfaces traced out by these deformations in three-dimensional space, for example:

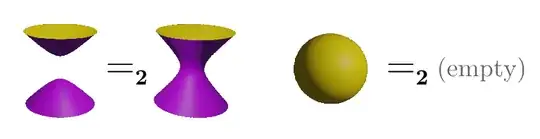

Since the lines are oriented, the surfaces will also be oriented, which I indicate by coloring each side with a different color (yellow/purple as in the famous sphere eversion movie). The allowed 2D-deformations for surfaces (for which I'll use the notation $=_\text{2D}$) include both "spherical" creation/annihilation (John Baez explicitly mentions this one) and "hyperbolic" joining/splitting:

plus the obvious topological motions, disallowing cusps, creases and similar singularities (i.e., the surfaces must remain immersions at every instant of time). So for example a torus, or really any higher genus closed surface without crossings, is 2D-deformation-equivalent to a sphere, which is in turn equivalent to the empty set. This lends credibility to the idea that only a few surfaces survive the reduction process.

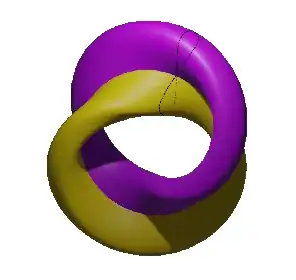

The generator $\eta^2$ of the second stable homotopy group of $\mathbb{S}$ is represented by the Cartesian product of two $\eta$s, which is 2D-deformation-equivalent to the surface obtained by taking the Cartesian product of $\eta$ by an interval, twisting one of the ends by $360$ degrees and gluing both ends:

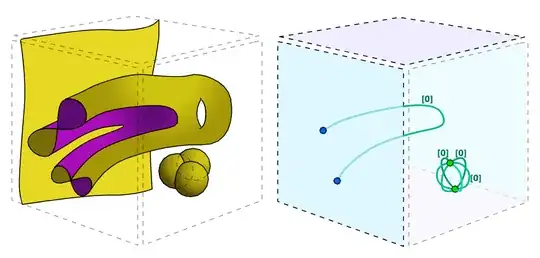

As before, there is a reduction process that takes as input a valid surface diagram and outputs a canonical representative, formed by a disjoint union of planes, the product of $\eta$ times an interval, and the above $\eta^2$ generator. However, so far I've been unable to figure out the steps of the process.

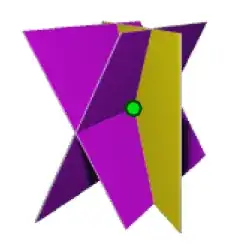

Generically two planes cross in a line, and three planes cross in a point. So in the general case, after slightly deforming the surfaces if necessary, the "crossing locus" is something like a graph, whose internal nodes where three surfaces cross have valence $6$ (and the external nodes have valence $1$), and where closed loops with no nodes are also allowed. Most likely this description would have to be supplemented with some information that accounts for orientation, to distinguish between $\eta^2$ and the trivial $\eta\times$ circle (I guess finding the proper description can be considered as part of my question). The internal nodes really do arise within valid configurations, e.g. there is a single internal node in the surface corresponding to the third Reidemester move (marked in green):

However, none of the objects (planes, $\eta \times \text{interval}$ and $\eta^2$) in the supposed final configuration have any internal nodes, so there must be a way to cancel them using allowed 2D motions.

Question

My question is:

What is the algorithm that reduces any valid two-dimensional surface diagram to a canonical representative in $\mathbb{Z} \oplus \mathbb{Z}_2 \eta \oplus \mathbb{Z}_2 \eta^2 \subset \mathbb{S}$?

In particular, what element do we obtain when applying it to the third-Reidemester-move surface? (it should be either $3+\eta$ or $3+\eta+\eta^2$). For the purposes of answering the question you may take as allowed motions only the ones I described above (regular homotopies between immersions plus the spherical and hyperbolic moves), unless the "obviously correct answer" uses some other motion.

If there is a reference that deals with this stuff, I would love to hear about it, especially if it also treats higher stable homotopy groups such as $\pi_3$.

(*): This is probably irrelevant, but the way I arrived at this question is by thinking about what would be the correct higher-dimensional generalization of Penrose diagrams, describing the categorification of (super) vector spaces. Some of them should arise as linear combinations of the diagrams in this question, so I need to understand them first.

($\dagger$): Actually, John Baez describes these line diagrams, or "tangles", as embedded in a space of higher dimension (at least four), so that everything is smooth, the crossings don't really exist and are just an artifact of the projection to 2D. But then everything becomes trivial when one adds negative elements, since the first Reidemester move is now allowed and $\eta$ can be turned into a circle. If one adopts this interpretation, some extra information is needed such as a stable framing (and this is enough since there is a known relationship between cobordisms of stably framed manifolds and the sphere spectrum). EDIT: The alternate interpretation in this question can be justified from the proof of Theorem A in this article by U. Koschorke, where the sphere spectrum is shown to correspond to oriented bordisms of immersed manifolds in codimension $1$. This lets us sidestep the tricky notion of a stable framing, and describe the sphere spectrum in terms of more familiar concepts such as orientations and crossings in a reasonably low dimension. I learned about this thanks to this post by Scott Carter, from the MO thread linked in Qiaochu Yuan's answer.