Ravi Vakil has these wonderful diagrams to make a lot of homological algebra extremely visual: https://www.3blue1brown.com/blog/exact-sequence-picturebook. My goal is to understand:

Goals: algorithm to construct, and proof of correctness

GOAL1: for a diagram in an abelian category $\underline{\mathcal A}$, how to draw an "accurate illustration" for it (and what does that even mean)?

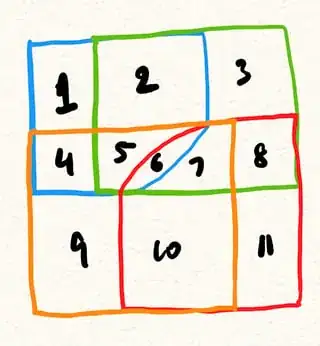

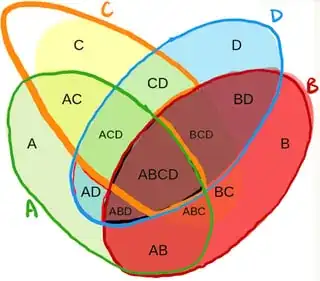

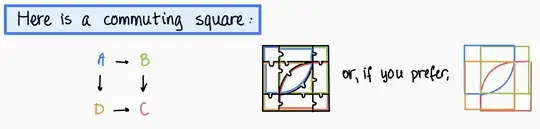

For instance, here's a diagram and Vakil's "accurate illustration" of it

GOAL2 (More important to me than GOAL1): given a candidate illustration, how do we prove that it is indeed accurate?

Defining "accurate illustration"

Definition: the upper left envelope (ULE) of a (compact; I guess throughout, we're implicitly taking closures of all sets) set $S\in \mathbb R^2$ is a copy of the 4th quadrant that envelopes $S$ as tightly as possible, i.e. $\{y\leq \sup \{y \in S\}, x \geq \inf\{x\in S\}\}$.

(

maybe even upper left convex envelope, intersections of all half spaces with normal vector in the 2nd quadrant.Hopefully this is not needed. Obvious generalizations for higher dimensions, though here I'm focused on $d=2$)Similar for lower right envelope (LRE).

Denote $B \subseteq \texttt{ULE}(A)$ by $A⌜B$, and $A \subseteq \texttt{LRE}(B)$ by $A⌟B$

Diagram to Illustration Dictionary

| In $\underline{\mathcal A}$ | In $\mathbb R^d$ |

|---|---|

| Object $A\in \underline{\mathcal A}$ | (compact) set $A\subseteq \mathbb R^d$ |

| Morphism $A\xrightarrow{f} B$ | pair of sets $(A,B)$, starting pairs should satisfy $A⌜B$ and $A⌟B$ |

| Composition: input $A\xrightarrow{f} B$, $B\xrightarrow{g} C$, output $A\xrightarrow{g \circ f} C$ | Input: $(A,B), (B,C) \leadsto$ Output: $(A,C)$ ; ($\color{red}{\text{abbr. } (A,B,C)}$) |

| $\ker(A \xrightarrow{f} B) := \text{Ker}(f) \hookrightarrow A$ | $(A,B)\leadsto (A\smallsetminus B, A)$ |

| $\text{coim}(A \xrightarrow{f} B) := A \twoheadrightarrow \text{Im}(f)$ | $(A,B)\leadsto (A, A \cap B)$ |

| $\text{im}(A \xrightarrow{f} B) := \text{Im}(f) \hookrightarrow B$ | $(A,B)\leadsto (A\cap B, B)$ |

| $\text{coker}(A \xrightarrow{f} B) := B \twoheadrightarrow \text{Coker}(f)$ | $(A,B)\leadsto (B, B\smallsetminus A)$ |

| $0$ object | set with $0$ volume |

| $A \xrightarrow{0} B$ zero map $\iff$ factor through $\text{Im} =$ obj. $0$ | pair $(A,B)$ s.t. $A \cap B$ is set of $0$ volume; denoted $(A,B)=0$ |

| monomorphism $A \hookrightarrow B \iff $ kernel is $0$ | pair $(A,B)$ s.t. $A \smallsetminus B$ is set of $0$ volume |

| epimorphism $A \twoheadrightarrow B \iff $ cokernel is $0$ | pair $(A,B)$ s.t. $B \smallsetminus A$ is set of $0$ volume |

| Univ. prop. of ker | Input: $(T,X), (X,Y)$ s.t. comp. $(T,Y)=0 \leadsto$ Output: $(T,X\smallsetminus Y)$ ; ($\color{red}{\text{abbr. } (T,X,Y)=0 \leadsto (T, X\smallsetminus Y, X,Y)}$) |

| Univ. prop. of coker | Input: $(X,Y), (Y,T)$ s.t. comp. $(X,T)=0 \leadsto$ Output: $(Y\smallsetminus X, T)$ ; ($\color{red}{\text{abbr. } (X,Y,T)=0 \leadsto (X,Y,Y \smallsetminus X, T)}$) |

Definition: a collection $\mathscr C$ of sets in $\mathbb R^d$ accurately illustrates a diagram (consisting of "initial/starting data" of $n$ objects, and some arrows between them in the abelian category $\underline{\mathcal A}$) is

some "starting" sets $S_1, \ldots, S_n$ corresponding to the "starting" objects, and "starting" pairs $(S_i,S_j)$ corresponding to the "starting" arrows, where we can use above rules/operations (5 total: composition, ker, coim, im, coker) to create new pairs (with possibly new sets)

any sequence of operations on pairs (which I'll denote by a vector $\vec O$ of operations $O$) performed on the $\mathbb R^d$ side, leading to a set (in one of the pairs say) of non-zero volume $\implies$ the same/corresponding operations $\vec O$ performed on the $\underline{\mathcal A}$ side results in a non-zero object in $\underline{\mathcal A}$

(and likewise, $\vec O$ leading to some set of $0$ volume $\implies \vec O$ leads to the $0$ object in $\underline{\mathcal A}$)

any 2 sequences of operations $\vec O_1, \vec O_2$ arriving at the same pair or same set $\implies \vec O_1, \vec O_2$ performed in $\underline{\mathcal A}$ produces the same morphism or same object (up to iso.)

(optional?) any "Indivisible Region" of the drawing in $\mathbb R^d$ can be attained from the "starting" sets/pairs by the 5 operations.

(optional?) for any 2 attainable sets $S, S'$ s.t. $S⌜S'$ and $S⌟S'$, we can obtain the pair $(S,S')$.

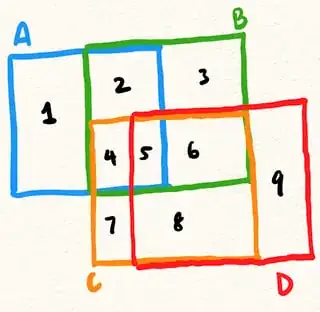

$\color{green}{\textbf{EXAMPLE:}}$ there are 11 "Indivisible Regions" in the above Vakil commuting square illustration (which I have numbered below), all of which correspond to some homological algebra object.

Here's an example sequence of operations to get to/isolate the region labelled 5 (it's quite an ordeal --- sorry for the numbering, I made a mistake and it was easier to do this than renumber):

| Pair # | Pair | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| -1 | $(\color{blue}{\underbrace{12456}_{A}}, \color{green}{\underbrace{235678}_B})$ | starting pair $A\to B$ |

| 0 | $(\color{blue}{\underbrace{12456}_{A}},256)$ | coim of Pair(-1) |

| 1 | $(\color{green}{\underbrace{235678}_B}, \color{red}{\underbrace{6781011}_{D}})$ | starting pair $B\to D$ |

| 2 | $(\color{blue}{\underbrace{12456}_{A}}, \color{red}{\underbrace{6781011}_{D}})$ | composition of Pair(-1),Pair1 |

| 3 | $(256,\color{red}{\underbrace{6781011}_{D}})$ | im of Pair2 |

| 4 | $(\color{blue}{\underbrace{12456}_{A}}, \color{orange}{\underbrace{4567910}_{C}})$ | starting pair $A\to C$ |

| 5 | $(12, \color{blue}{\underbrace{12456}_{A}})$ | ker of Pair4 |

| 6 | $(12, 256)$ | composition of Pair2,Pair5 |

| 7 | $(256,56)$ | coker of Pair6 |

| 8 | $(256,6)$ | coim of Pair3 |

| 9 | $(25,256)$ | ker of Pair8 |

| 10 | $(25,56)$ | composition of Pair9,Pair7 |

| 11 | $(25,5),(5,56)$ | coim,im of Pair10 |

I'm pretty sure Vakil's commuting square illustration satisfies (1),(2),(3),(4) from the Definition of accurate illustration. It might even satisfy (5).

Example of satisfying (5): $(456, 67)$. First, $$(A,C) \xrightarrow{\text{im}} (456,C)\xrightarrow{\text{comp.}} (456,D) \xrightarrow{\text{coim}} (456,6).$$ And above, I already constructed $(5,56)\xrightarrow{\text{coker}} (56,6)$, so doing the dual of the above operations, I can construct $(6,67)$. Then taking the composition of the previous two steps, I arrive at $(456,67)$ as desired.

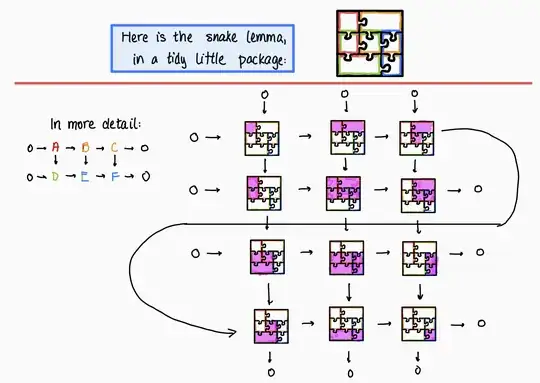

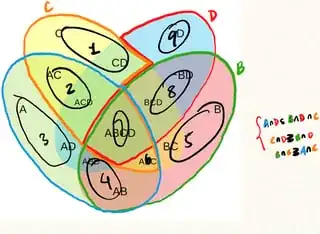

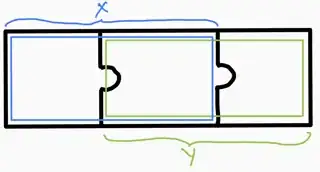

$\color{green}{\textbf{EXAMPLE (snake lemma):}}$ numbering the 7 "Indivisible Regions" in the illustration below (1,2 on top row; 3,4,5 on middle row; 6,7 on bottom row)

we can construct the famous connecting morphism $(24,46)$ as follows (a "translation" of this proof): with compositions of the "starting arrows" in the original diagram, we can get to $(A,B, F)$. Then, $$(A,B,F)=0 \xrightarrow{\text{univ. prop. ker.}} (A, 1234, B, F).$$ Then $(B,F) \xrightarrow{\text{ker.}}(1234,B,F)=0$ composed with $(B,E, F)$ gets us to $$(1234, E, F)=0\xrightarrow{\text{univ. prop. ker.}} (1234, D,E,F).$$ Finally, $(A,D) \xrightarrow{\text{coker.}} (A=13,D=346, 46)=0,$ and so taking compositions of the above, we get $$(A,1234,46)=0 \xrightarrow{\text{univ. prop. coker.}} (A=13,1234, 24,46).$$

Ideas for Algorithm to Construct ("Subimage Constraint")

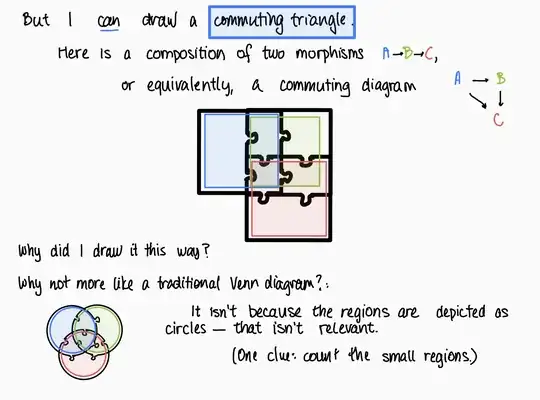

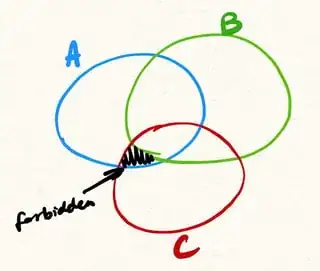

Example 1: Triangle

One idea is to start with the most general possible Venn diagram for $n$ objects, and then whittle away some of the sets to get rid of "impossible regions". For example Vakil has

where the forbidden piece is:

because (thinking in the category $\underline{R\textsf{-mod}}$ for concreteness) the module $\text{Im}(A\to C)$ should be a submodule of $\text{Im}(B\to C)$ (submodule of $C$), i.e. in the illustration, we should have $A \cap C \subseteq B \cap D$.

Example 2: Square

We can try this for the diagram:

$$\begin{array}{ccc} C & \to & D \\ \downarrow & & \downarrow \\ A& \to & B \end{array}$$

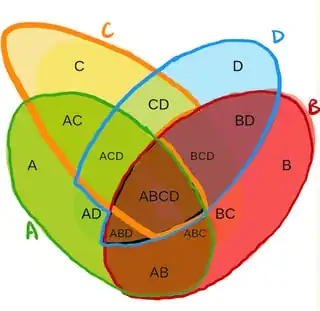

The same "subimage constraint" gives the following 2 constraints for the sets in the illustration: $C\cap B \subseteq D \cap B$, $C \cap B \subseteq A \cap B$. Whittling away the 4-set general Venn diagram (actually I only need to change the shape of $C$), we get

I think this satisfies (1), (2), (3) of the definition of accurate illustration above, but not (4) because of the extra "Indivisible Region" labelled "AD" in the picture.

Removing the Region "AD" (by changing the shape of $D$), we get

which has 11 "Indivisible Regions", as Vakil's does (first picture in this long post). Hence, it is an accurate illustration of a commuting square (iff Vakil's is too).

Example 3: Zigzag

Finally, this idea of only using the "subimage constraints" also works (I think) for the diagram $$\begin{array}{ccc} A & \to & B & & \\ & &\downarrow & & \\ & &C& \to & D \end{array}$$

(which one can think of as the previous commuting square diagram, but adding one morphism from the upper right corner of the square to the lower left corner of the square).

I think this is an accurate illustration (but can not rigorously show it):

which has 9 "Indivisible Regions", as predicted using just the "subimage constraints" $$A \cap D \subseteq B \cap D, C \cap D$$ $$C \cap D \supseteq B \cap D$$ $$B \cap C \supseteq A \cap C$$ which yield the following "whittled" 4-set Venn diagram (ignore how the relative positions of $A,B,C,D$ do not match the above diagram; that's not the point here. The count of 9 indivisible regions is the point here.)

Idea for Proof of Correctness

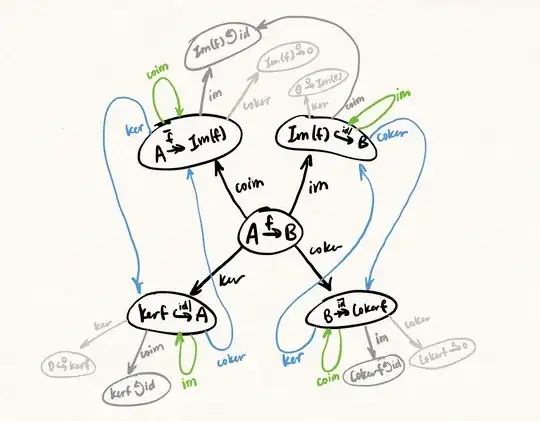

For the simplest diagram (a single morphism),

I can write out all the relationships, and verify that the illustration is accurate:

$\color{red}{\text{But sadly this spirals out of control for any harder diagram :(}}$

Restating the Goals (i.e. what I'm asking in this question)

GOAL1: for a diagram in an abelian category $\underline{\mathcal A}$, what is a algorithm to draw an accurate illustration for it, as defined above?

GOAL2 (More important to me than GOAL1): given a candidate illustration, how do we prove that it is indeed accurate?

EDIT (addressing a comment, regarding what the "point" is to these illustrations): I can't speak for anybody else, but before Vakil's diagrams, the snake lemma always felt very "coincidental". Only by seeing the exact sequence visually, am I finally able to understand the snake lemma as "natural"/"obvious"/"inevitable". Even something as basic as the definition of (co)homology never truly "settled" in me, until I saw them in Vakil's illustration of a chain complex.

More generally, I was never able to "see" the LES in (co)homology, since on top of the SES of chain complexes, one needs to add in a lot of extra objects. Even the 3D figure in these notes (pg. 10) don't contain all the objects that show up in the construction. I was able to draw a figure, but it's a complete mess (to view full image, click the image, and change s.jpg to .jpg):

And spectral sequences, infamously tricky to teach, finally feel within reach to me (even after learning the formalism repeatedly before this).

So: (1) the purpose is to help students out there (such as myself) who would benefit from this picture-based homological algebra (I know it's already succeeded for at least one person); (2) yes the illustrations do simplify the complex web of objects and arrows; and (3) yes Vakil's big snake lemma illustration does help me.

Finally, Tao coincidentally posted essentially these same ideas on his blog at around the same time (late 2021); I can tell both Vakil and Tao spent a lot of time and effort on their writeups, so I think it's fair to say they found it valuable, and in fact instructive (cf. Vakil's "Until now, I never realized...")! Not to "appeal to authority", but if these 2 well respected mathematicians/teachers find value in these illustrations (even in the face of their limitations, e.g. Tao's "limitations to this notation..."), and in fact discovered them independently, then it shouldn't be that hard to believe that other people/students (e.g. me, Reddit1, Reddit2, D. Litt) may find them very insightful too!

And if you're still worried about perpetuating "all sorts of wrong stuff about algebraic structures", that's why I'm trying to establish a rigorous and careful framework here.