Define

$$ g_n(x) = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } n = 1, \\ x + g_{n-1}(x), & \text{if } n > 1 \text{ is prime}, \\ \prod_{p \mid n} \left( g_p(x) \right)^{v_p(n)}, & \text{if } n > 1 \text{ is composite}. \end{cases} $$

Here are some of these polynomials:

1 1

2 x + 1

3 2*x + 1

4 x^2 + 2*x + 1

5 x^2 + 3*x + 1

6 2*x^2 + 3*x + 1

7 2*x^2 + 4*x + 1

8 x^3 + 3*x^2 + 3*x + 1

9 4*x^2 + 4*x + 1

10 x^3 + 4*x^2 + 4*x + 1

11 x^3 + 4*x^2 + 5*x + 1

12 2*x^3 + 5*x^2 + 4*x + 1

13 2*x^3 + 5*x^2 + 5*x + 1

14 2*x^3 + 6*x^2 + 5*x + 1

15 2*x^3 + 7*x^2 + 5*x + 1

16 x^4 + 4*x^3 + 6*x^2 + 4*x + 1

17 x^4 + 4*x^3 + 6*x^2 + 5*x + 1

18 4*x^3 + 8*x^2 + 5*x + 1

19 4*x^3 + 8*x^2 + 6*x + 1

20 x^4 + 5*x^3 + 8*x^2 + 5*x + 1

21 4*x^3 + 10*x^2 + 6*x + 1

22 x^4 + 5*x^3 + 9*x^2 + 6*x + 1

23 x^4 + 5*x^3 + 9*x^2 + 7*x + 1

It seems that empirically we have $\forall n \ge 2$ the polynomial $g_n(x)$ is a Hurwitz polynomial, wich by definition means it has real coefficients and all of its roots have real value $<0$.

This observation with the Lemma which comes afterwards would explain why for $p$ prime we have $g_p(x)$ is irreducible.

For prime $p$ it seems that $g_p(x)$ is always irreducible:

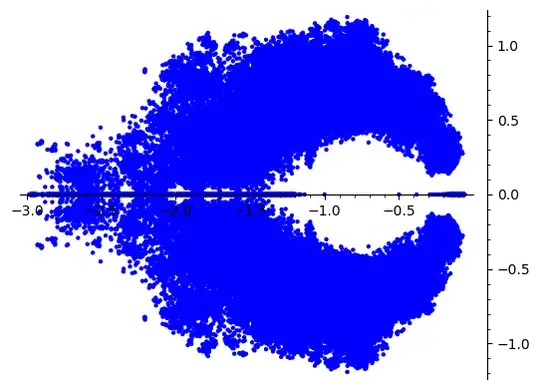

This could be proved if $\operatorname{Re}(z)<0<\frac{1}{2}$ for all roots $z$ of the polynomial $g_p(x)$. Here is a picture of collected roots of some $g_p(x)$ with $p$ prime $\le 100000$. If all roots have real value $<1-1/2$ then the following Lemma could be applied to the polynomial $P(x):=g_p(x)$ with $n=1$, since $p=g_p(1) = g_p(n)$ is a prime number and $g_p(n-1) = g_p(1-1) = g_p(0) = 1 \neq 0 $:

Lemma (B. Sury, Polynomials with Integer Values, Lemma 1.9):

Let $ P(X) \in \mathbb{Z}[X] $ be a polynomial, and suppose there exists an integer $ n $ such that:

- The zeros of $P$ lie in the half-plane $ \text{Re}(z) < n - \frac{1}{2} $.

- $P(n - 1) \neq 0$.

- $P(n)$ is a prime number.

Then $P(X)$ is irreducible.

Edit: With the comment (for $p\ge 3,$ prime and $\operatorname{Re}(z)\ge 1/2$ we have $|g_p(z)|>2|z|$, which would prove by Lemma of Sury, the irreducibility.) from Jonathan Love, I can verify:

For $p = 2$: If $\mathrm{Re}(z) \geq 1/2$ and $z = a + b i$, then

$$ |g_p(z)| = |z+1| = \sqrt{(a+1)^2 + b^2} \geq \max(3/2, |z|). $$

For $p = 3$: If $\mathrm{Re}(z) \geq 1/2$ and $z = a + b i$, then

$$ |g_p(z)| = |2z+1| = \sqrt{(2a+1)^2 + (2b)^2} > \sqrt{(2a)^2 + (2b)^2} = 2|z|. $$

Let now $p > 3$ and suppose that a prime $q > 3$ divides $p-1$. Then we get:

$$ |g_p(z)| = |z + g_{p-1}(z)| \geq \text{(reverse triangle inequality)} \; |g_{p-1}(z)| - |z|. $$

But

$$ |g_{p-1}(z)| = |z+1|^{v_2(p-1)} \cdot |g_q(z)|^{v_q(p-1)} \cdot \prod_{r | (p-1), r \neq q} |g_r(z)|^{v_r(p-1)}, $$

and from the case $p = 2$ and induction on $p$, we get:

$$ |z+1| \geq 3/2, \quad |g_q(z)| > 2|z|. $$

After multiplying the terms, we have:

$$ |g_{p-1}(z)| > \frac{3}{2} \cdot 2|z| = 3|z|, $$

and therefore

$$ |g_p(z)| \geq |g_{p-1}(z)| - |z| > 3|z| - |z| = 2|z|. $$

This proves the inequality in this case.

It remains to discuss the case where $p-1 = 2^k$ with $k \geq 2$. which I do not see now, and any help is appreciated.

Related question: https://mathoverflow.net/questions/485027/are-these-polynomials-g-nx-for-n-ge-2-hurwitz-polynomials