I am looking to find an intuition for how powers of the $\text{sinc}$ function behave. Just for context, the $\text{sinc}$ function I'm looking at is the "unnormalized" one:

$$ \text{sinc}(x) = \begin{cases} 1 &\text{if}\, x = 0\\ \frac {\sin x} {x} &\text{otherwise.} \end{cases} $$

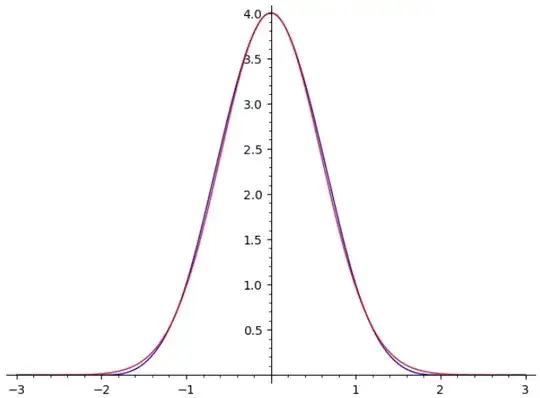

Consider this sequence of functions:

$$ f_n(x):= \text{sinc} \left( \sqrt{\dfrac{3}{n}} \cdot x \right) ^ {n} $$

where $n \in \mathbb{Z}$. As $n \to \infty$, my conjecture is that $f_n \to g$ uniformly, where $g$ is a Gaussian function:

$$ g(x) := \exp {\left( -x^2 / 2 \right)} $$

Expanding the Taylor series of $f_n$ and $g$ around $x = 0$, I obtain:

$$ f_n(x) = 1 - \frac{1}{2} x^2 + \left( \frac{1}{8} - \frac{1}{20n} \right) x^4 - \left( \frac{1}{48} - \frac{1}{40n} + \frac{1}{105n^2} \right) x^6 + \left( \frac{1}{384} - \frac{1}{160n} + \frac{101}{16800n^2} - \frac{3}{1400n^3} \right) x^8 + O(x^{10}) \\ g(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}{\dfrac{(-1)^k x^{2k}}{2^k k!}} = 1 - \frac{1}{2} x^2 + \frac{1}{8} x^4 - \frac{1}{48} x^6 + \frac{1}{384} x^8 + O(x^{10}) \\ $$

(I expanded the series for $f_n$ by way of reference to this question & using Wolfram Alpha.)

I can see that the terms with $n$ in the denominator in the series coefficients for $f_n$ will vanish as $n \to \infty$, leaving only the leading term. Inspecting the first dozen or so of those leading terms confirms they equal the coefficients in the series for $g$, reinforcing my suspicion that $f_n \to g$ uniformly.

But simply comparing the "first few" coefficients by inspection leaves me feeling... unenlightened. Is there an elegant way to prove that $f_n \to g$ uniformly? Would it be sufficient to prove that the non-vanishing terms in the coefficients of the series expansion for $f_n$ will continue to equal $\frac{(-1)^k}{2^k k!}$ out to $k=\infty$? And if so, how does one approach that proof?

(And, by the way: is there any particular underlying intuition for why the argument of $\text{sinc}$ must be scaled by a factor of $\sqrt{3}$?)

More broadly: are there some more general mathematical concepts I can leverage to better understand what's going on? Looking at the generality of results like the central limit theorem, as well as questions like this - is it just incidental that $\text{sinc}$ was the function I happened to be messing around with this one particular lazy Sunday, and actually this type of convergence to a Gaussian happens for a much wider class of sequences of functions? My interest here is purely recreational (and this isn't "for" anything in particular)... so more abstract answers / hand-wavey "proofs" / generalized discussion / nudges in the right direction for me to run with the rest of the way are all very welcome. ;)

Thank you!