Standard high school geometry courses cover the Triangle Inequality, which states that if $a,b,c$ are three sides of a triangle, then $$a + b > c \qquad a + c > b \qquad b + c > a$$ I'm interested in the converse:

If $a,b,c$ are three positive real numbers satisfying the above three constraints, does there exist a triangle with those three lengths as the side lengths?

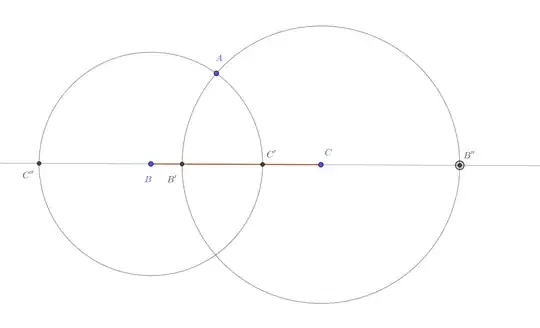

I'm not sure how to tackle a question like this in the axiomatic system used in a high school geometry course. If we use a coordinate system, then it should be easy to specify the vertices of the appropriate triangle, but what if we stick fully within the confines of classical geometry, where points are not given coordinates?